Introduction

This continues from the first part of the story posted a week ago.

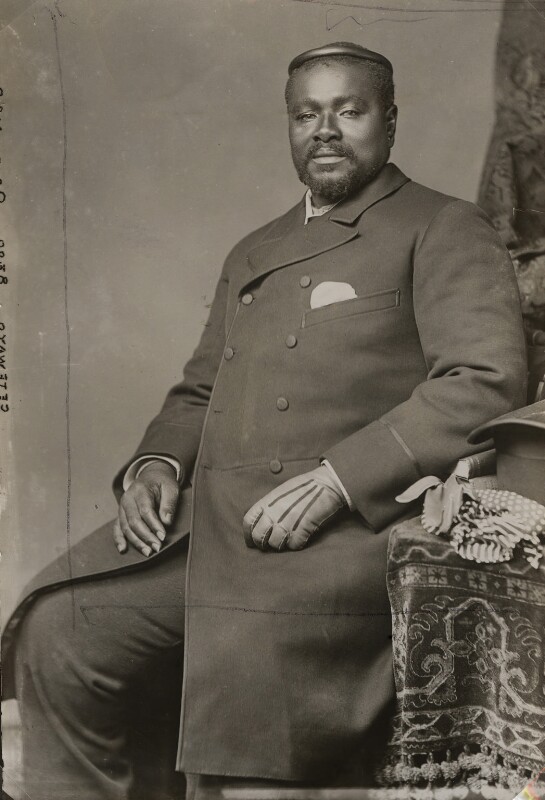

WILLIAM DUNCAN, 1846-1921 Part 2 of 2

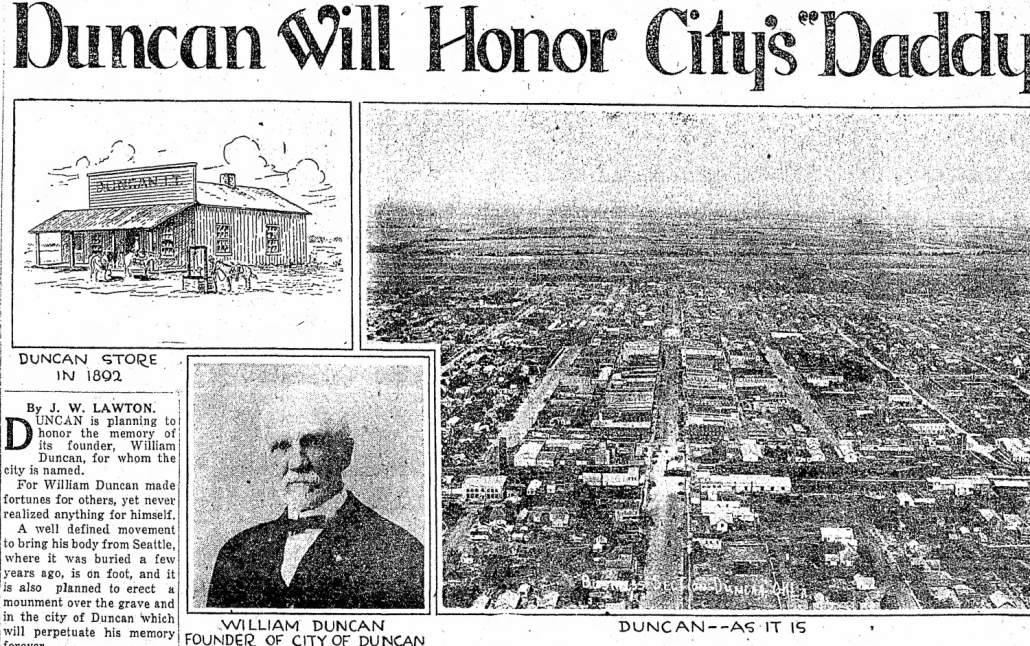

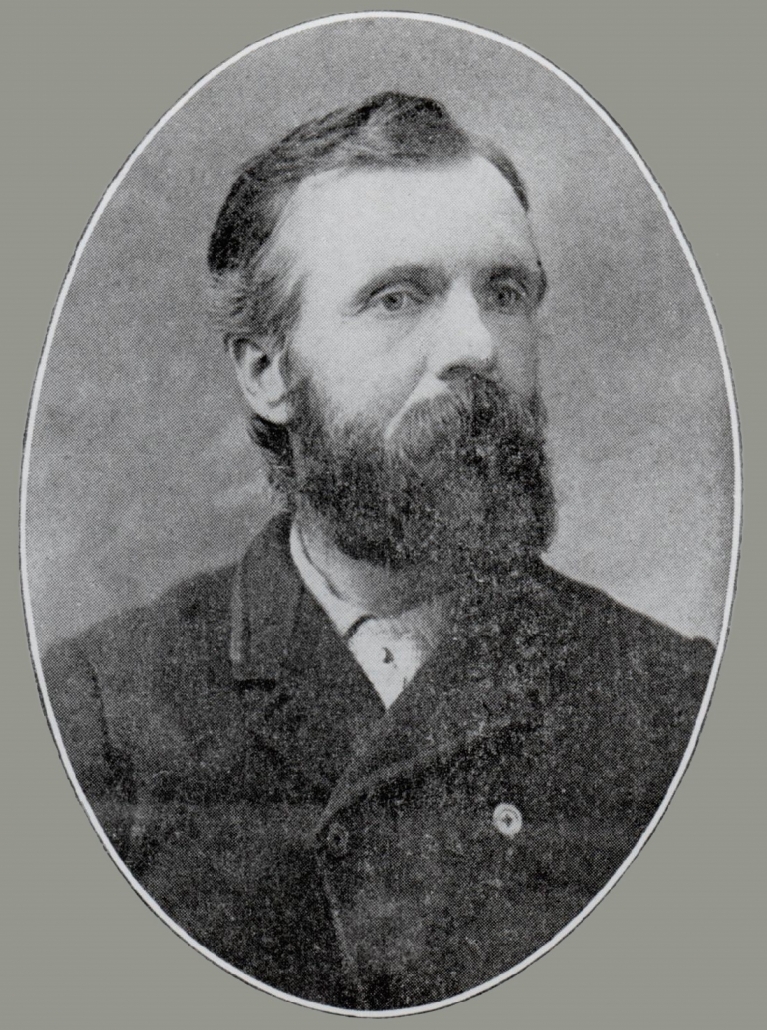

William Duncan was a very enterprising man. He was on various committees and organised the first Masonic Lodges in the Chickasaw Nation. Through his connections as a Scottish Rite Shriner, he heard that the Rock Island Railroad was to be extended and built across his land. He immediately ordered a new store to be built nearer to the railroad site as well as new homes for himself and family members. William had always held the Native Indian people in high regard but ignored their advice not to build his new store in the location he had chosen near the new railway line. They warned him it would be right in the cyclone path but William had already made promises to rail road officials so he went ahead.

The area was unfortunately struck by cyclones several times over the years with a particularly bad one in 1898 flattening most of the town. The demolished buildings were rebuilt with stronger materials and life went on.

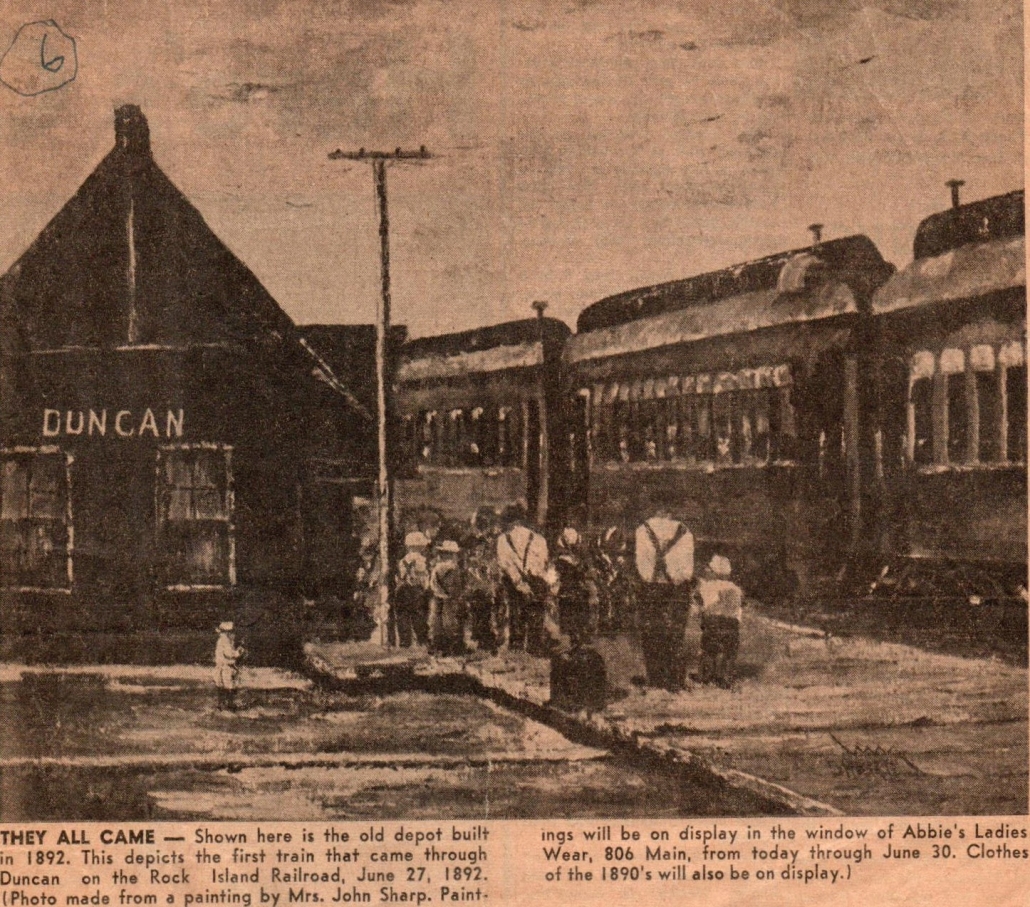

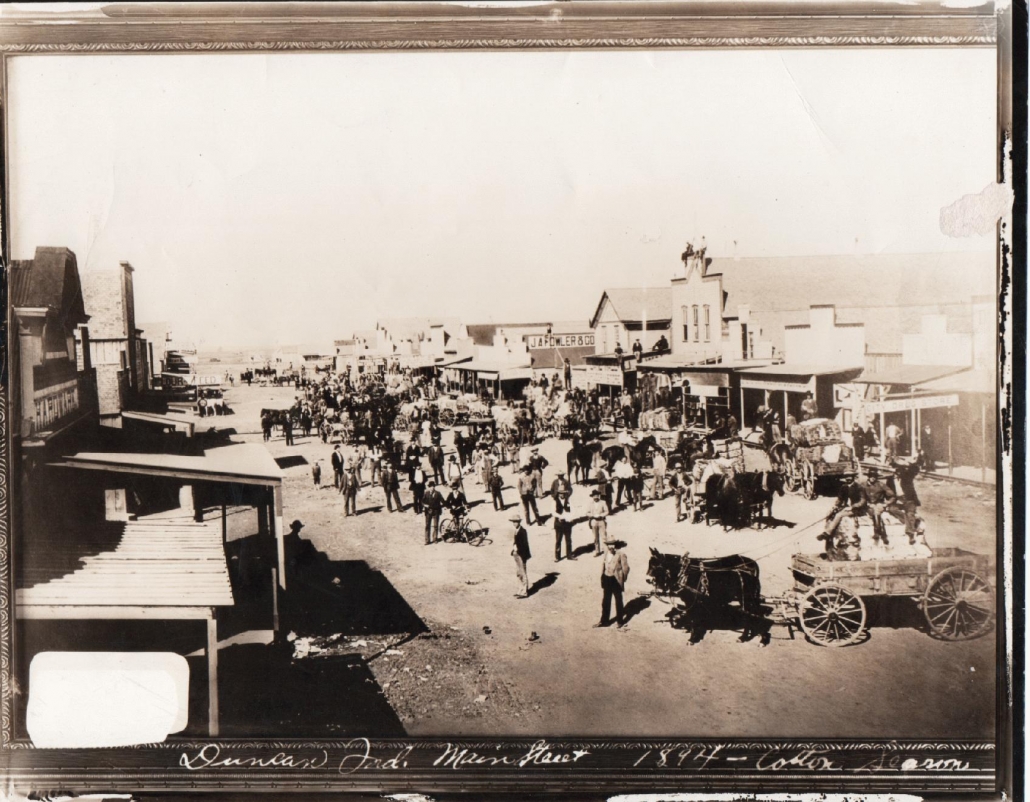

He established ‘city’ limits when other families started to arrive. The town of Duncan was officially named on 27th June 1892 when the first train passed through. By all accounts it was a day of great celebration opening up endless possibilities for the small town, bringing goods and passengers faster than by road and was a mechanical link to the rest of the country. The Duncan band played and there was a party and barbeque which lasted for three days. Chief Quanah Parker, the last Comanche Chief, attended with hundreds of his ‘braves’ from their reservation near Fort Sill, making a colourful sight and a great time was had by all. The anniversary of that day was celebrated for many years after with people coming from miles away in wagons, buggies and on horseback.

1892 was also a sad year for the Duncan family as William’s other two daughters, Ruth and Christina, died of typhoid fever when it swept through the country and they are buried next to their Macduff grandmother, Ann. All three daughters were gone but William still had his three sons, William junior known as ‘Red Bill’, James known as ‘Big Jim’ and Gregg. That same year William ordered the building of the first Baptist Church in ‘Duncan’ which also served as a meeting place. The first school followed soon after.

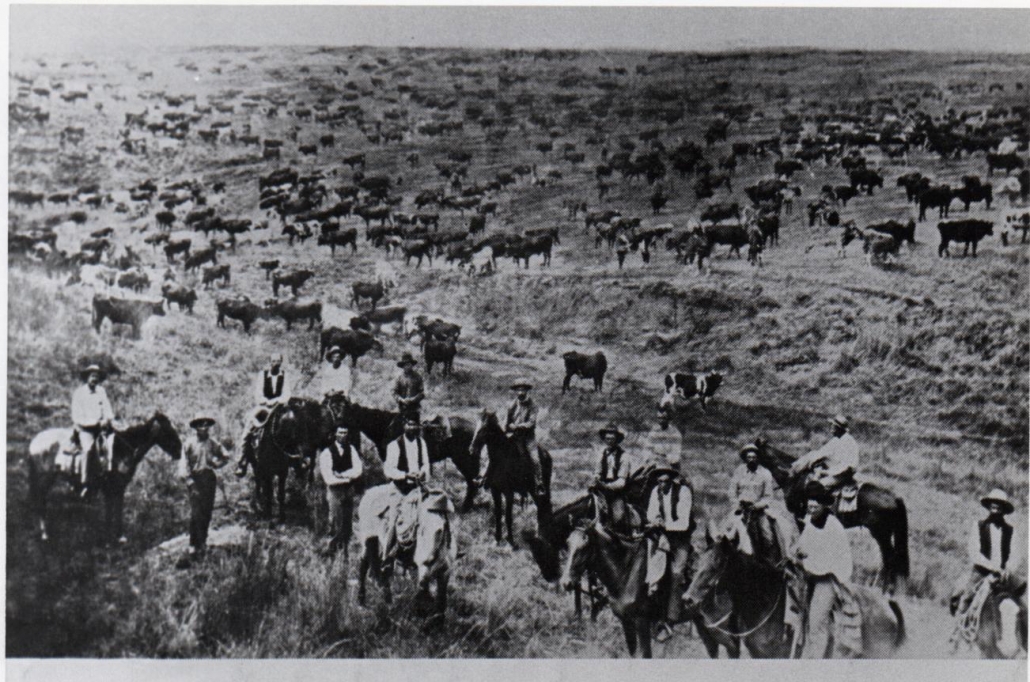

In 1895, William sold his store, gave up his position as postmaster and concentrated on rearing dairy cattle. William wanted to share his good fortune and encouraged other family members from Scotland to join him. His sister, Isabella Duncan had a large family and two of her daughters, Agnes and Barbara Kelman and a son, Alex Kelman travelled over one by one and made their home there.

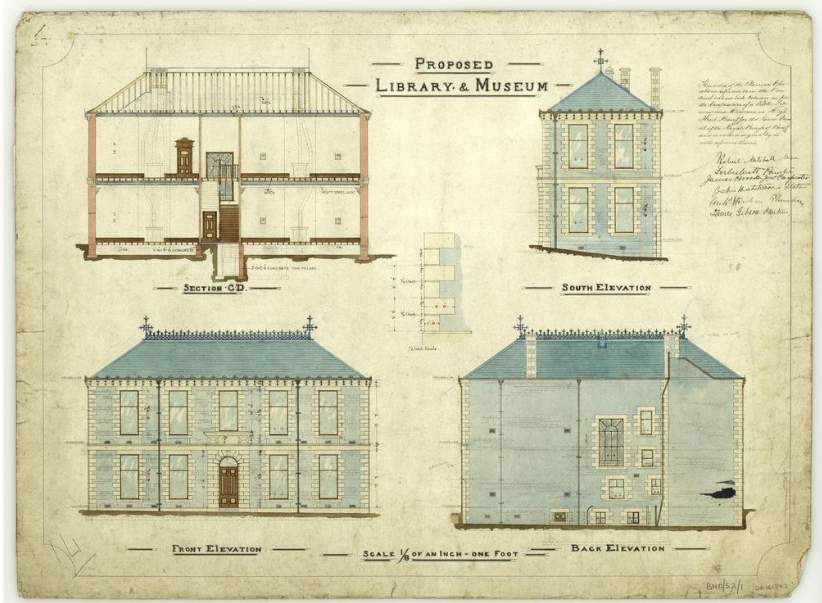

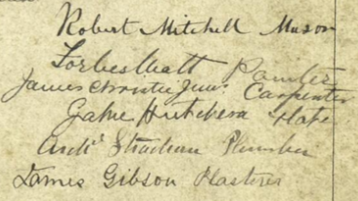

Alex Kelman became one of the best known ‘ropers and riders’ at rodeos in the country but tragically died age 40 when he was thrown from his horse. William’s brother James also had two sons, William and Jim Duncan who left Scotland and settled in Duncan, Oklahoma. Out-with his own family, he paid for several other young Scots to travel over, using their skills to help build his town. In return, they settled there and had good lives.

William was described as being cultured, refined and a fine conversationalist, liberal to a fault and never forgetting a friend or those in distress, indulgent to his family and a moral, upstanding man. Mrs Geneva Thurlo, wife of US Marshall Ed Thurlo of the town described William Duncan as being “one of the finest, kindest men I have ever known”.

In 1905, William and Sallie, affectionately known in the town as Uncle Bill and Aunt Sallie, decided to retire due to William’s failing health. They moved, at first, to California to be nearer to son, Jim’s family. Later, they moved again to Bremerton, Washington to be nearer the sea which served as a reminder of William’s homeland. Sallie died there in 1914.

1907 brought statehood to the Indian and Oklahoma Territories and Duncan was made the county seat of Stephens County. It became the 46th state to enter the Union.

In 1919, William and his great niece travelled back to Duncan, Oklahoma for a visit. William did not recognise the place. It was bustling with faces he did not recognise. The population was growing especially since the recent discovery of oil in the region. He suffered a short illness while there and was unable to return home for a few weeks.

William Duncan died in Bremerton in 1921. His legacy is the town, now a city, which was named after him and the many Scots people who followed him to Oklahoma. There is no statue or memorial for him. There is one for Earle P. Haliburton who founded the oil company based there.

Note from the author Sonia Packer:

My information has been gathered over many months from descendants of the Duncan family including direct descendants of William Duncan who hold stories and photographs; from archives and news stories; from the Stephens County Historical Museum in Duncan, who have a portrait and personal possessions that belonged to William and from the Oklahoma History site. The Chisholm Trail Heritage Centre is also in Duncan, Oklahoma.

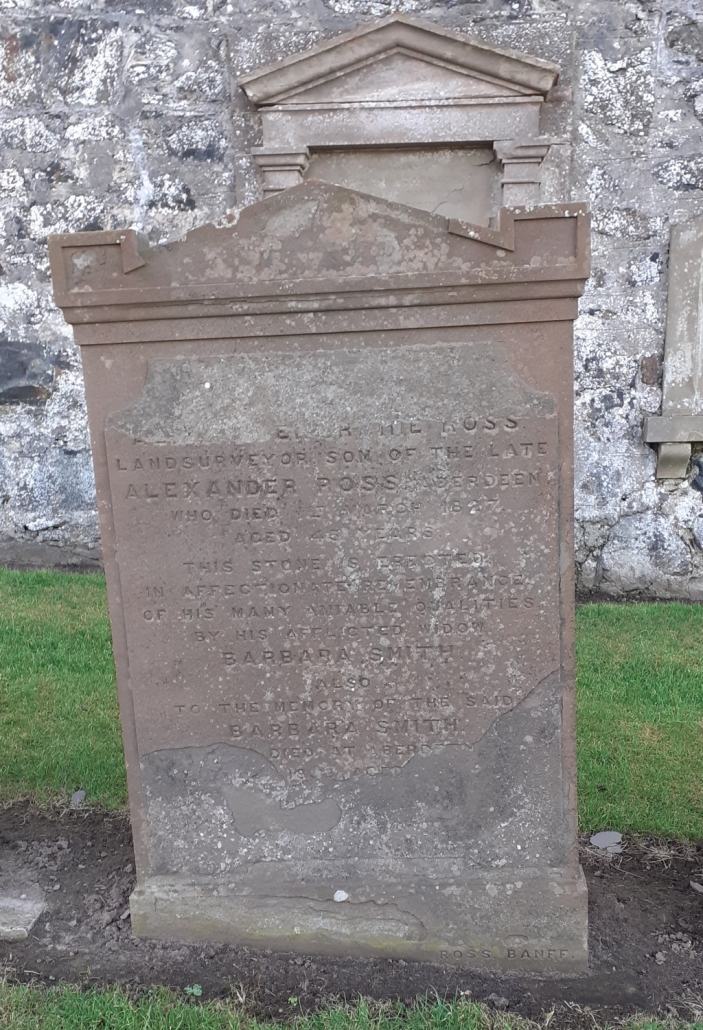

I descend from William’s sister, Annie Duncan who married a farmer and lived in Alvah, Banffshire all her life. William was my 2 x great uncle. William’s mother, Ann Kinnaird was my maternal 3 x great grandmother. Her sister, Helen Kinnaird, who married James Watt, a fisherman from Crovie, Gardenstown was my paternal 2 x great grandmother. Helen’s 2x great grandsons are the founders of Macduff Shipyards.

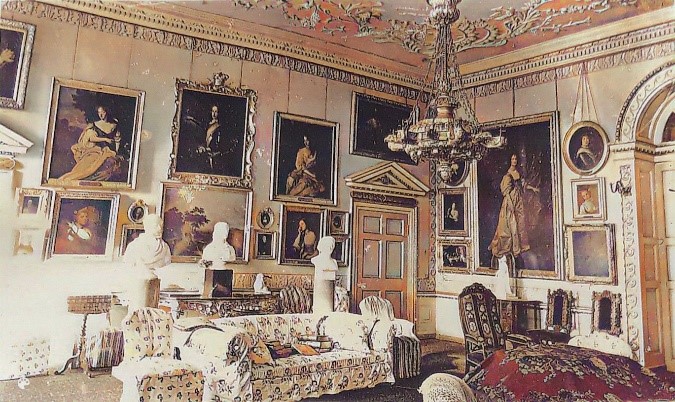

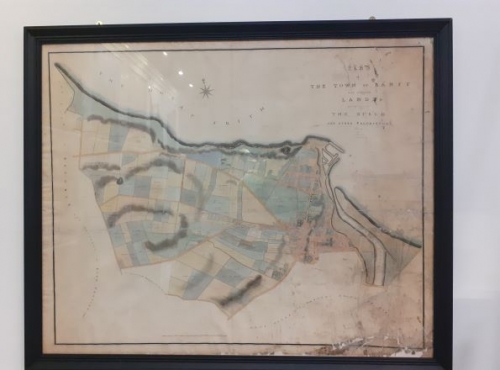

Banff Preservation and Heritage Society and Museum of Banff

Banff Preservation and Heritage Society and Museum of Banff

Andrew Taylor

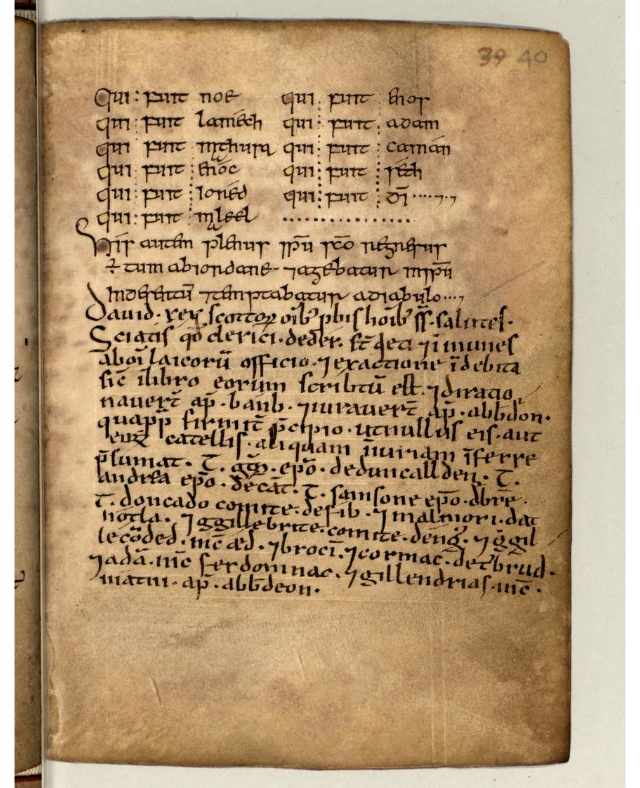

Andrew Taylor © The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum