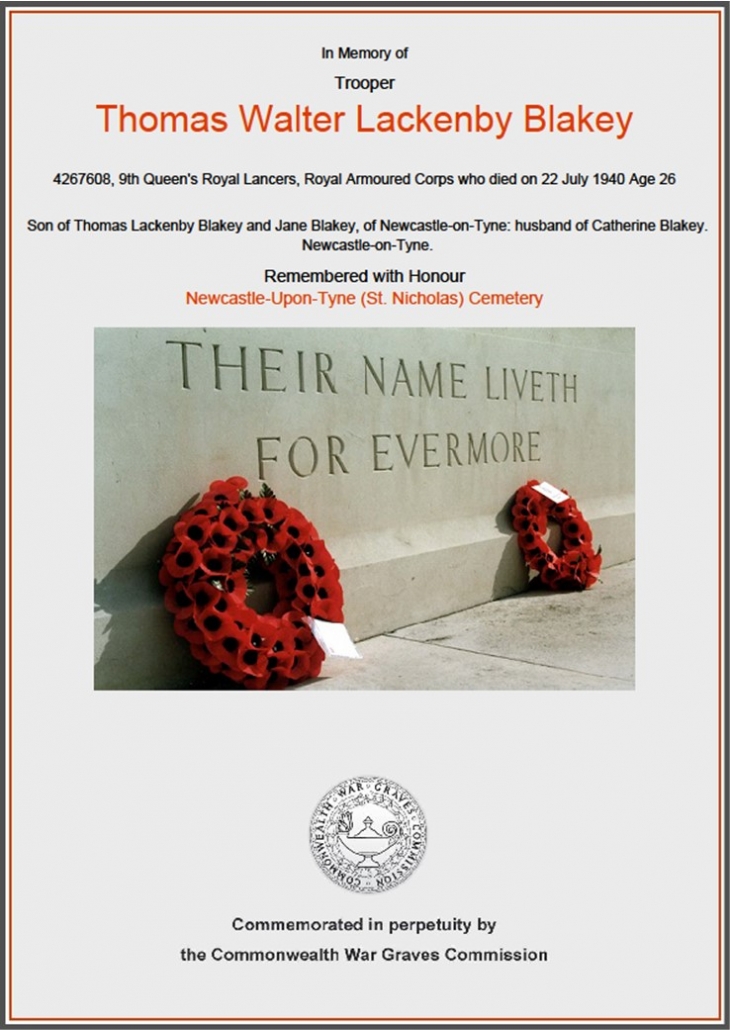

The bombing of the Duff House Prisoner of War camp on 22nd July 1940 is well known – there are other stories on this website and a book by the Friends of Duff House, “Out of the Blue”; not least the joint British and German memorial outside Duff House close to where one of the bombs exploded.

There are however several so far unexplained mysteries around the whole matter of PoW Camp No5; ie Duff House.

Why were there so many regiments represented at Duff House in July 1940. We know – mainly from the hospital records – that men from at least 8 regiments were stationed here.

Secondly, although the British did a monthly report called “General Return of the Strength of the British Army”, Duff House is not listed as having any soldiers in July 1940 – although clearly there were!

Thirdly, is this tied in with why there is no MoD file on PoW Camp No5 ? There is a file on 4 and 6, but no 5 – or at least not until 1944 when PoW Camp 5 was opened at Cookstown in Northern Ireland. Yet there is a 1940 War Office letter referring to Duff House and PoW Camp No5, so there Is firm evidence!

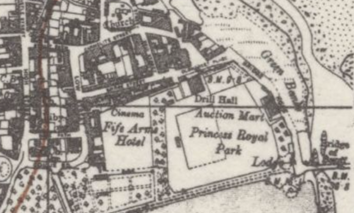

Fourthly, what was the reason that the prisoners were housed inside Duff House itself, and the guards were in the Nissen huts to the east? We know for sure the prisoners were inside, we even know which rooms some of them had, based on their own later correspondence.

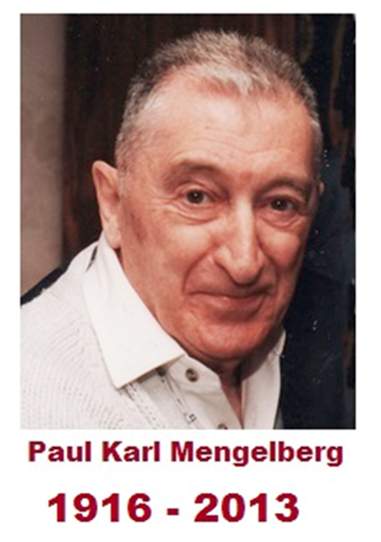

But the biggest mystery of all might be just why was the whole crew, except the captain, of the U-26, were transported all the way from southern Ireland to the north of Scotland. An admission from the submarine radio operator, to a Canadian radio station, a couple of years before he died in 2013 might provide a clue. Previous reports had always implied that the Germans had sunk the submarine before the British, from HMS Rochester, had been able to get on board, even though every single German crew member was rescued. But Paul Mengelberg amended this in his radio interview, and admitted that the British did board the submarine.

There is no evidence but one possible reason this had not become known earlier, and perhaps explaining why 40 Germans had been transported hundreds of miles to Banff, has to do with the code that the Germans were using, and the British were trying to break – the Enigma machine. The official records show that the British were not able to read the german messages until at least March 1941. But did they actually get their hands on an enigma machine in July 1940 – and needed to keep that quiet so the Germans would not know they were reading messages?

It seems unlikely we’ll ever know, but it is intriguing that Duff House may have been part of such an important element in the war.

Andrew Taylor

Andrew Taylor © The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum