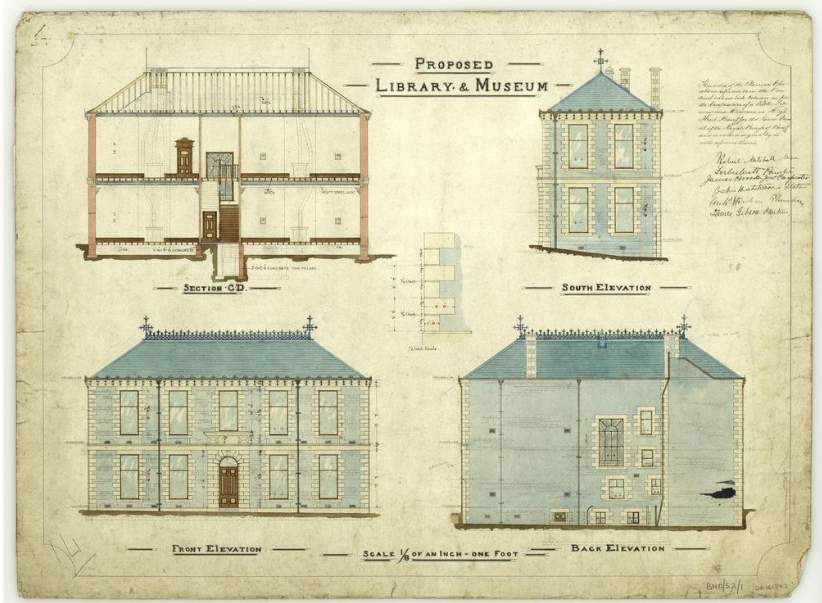

While completing the paperwork to enable the Museum of Banff to be involved in this year’s Doors Open Day, the name of the architect of the Banff Library and Museum emerged, one C. W. Cosser, and, as it is an unusual name for Banff, I sensed a story.

Charles Walter Cossar, or more often Cosser, was indeed the architect based in Banff who designed the Banff Library building.

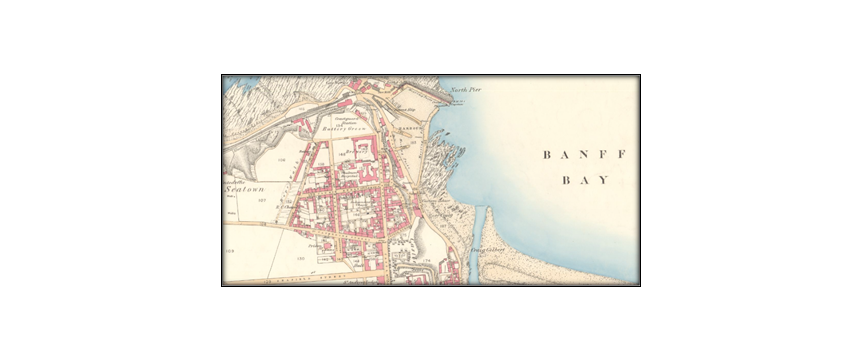

Charles Cosser was born in Southampton and is listed as a Bugler with the Royal Engineers in 1861. He first arrived in Banff as an engineer with the Royal Engineers in 1866, when they carried out a survey of the district. Later he retired from the army and married a local butcher’s daughter, Mary Ann Bartlett Scott, in 1870. They had four children. Unfortunately his wife died in 1874.

He was responsible for a number of projects in the local area such as adding the tower to Portsoy Parish Church in Seafield Street in 1876.

C.W. Cosser also designed alterations for Craigston Castle in 1876, alterations to the Royal Oak hotel in the 1890s, and planned the extension to Marnoch Churchyard in 1902. He also built Doctor Barclay’s house in Castle Street. He was praised for his work as an engineer in 1888 as he was responsible for planning a clean water supply for Ladysbridge, bringing it from springs on the farms of Wardend and Inchdrewer.

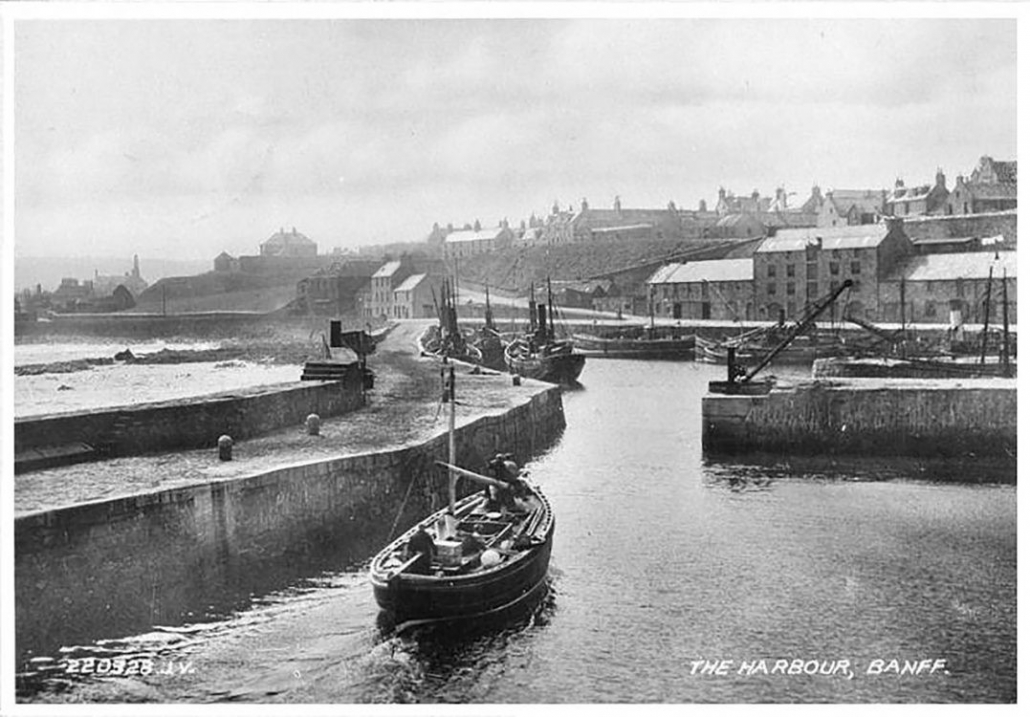

As well as being an architect and surveyor Charles had other roles: he was Inspector of the Poor, and people could book passages on board ships to worldwide destinations from his offices at 1 Carmelite Street.

Charles also held the role of Clerk to the Parish Council and he rented out several properties around Banff.

In his spare time, we know that he kept a garden because he was a Banff Flower Show winner in the amateur section for dessert apples – truly a man o’ pairts.

Charles Walter Cosser died in Banff in 1915, aged 70.

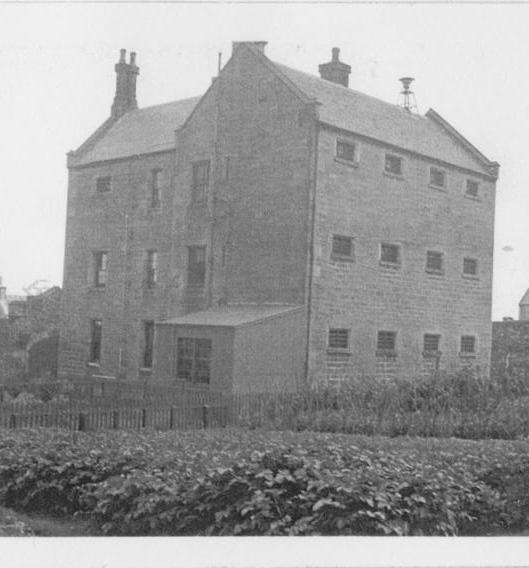

Portsoy Church, Seafield Street.

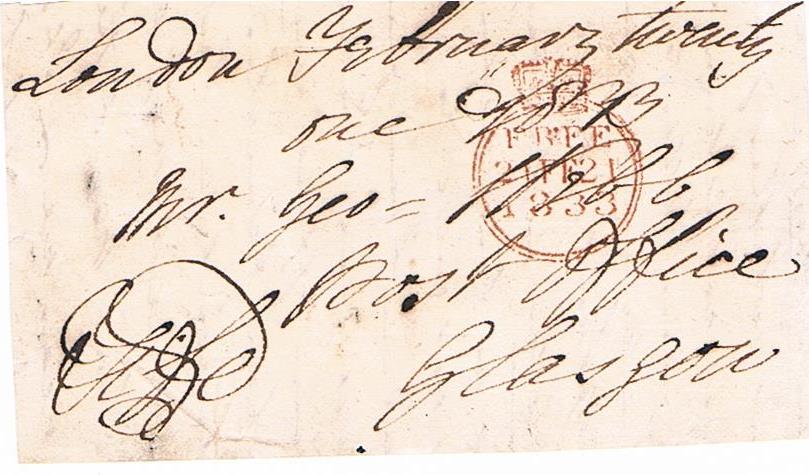

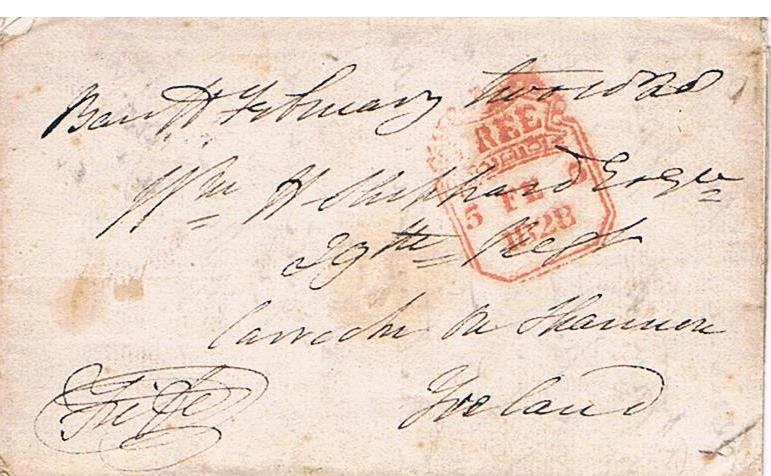

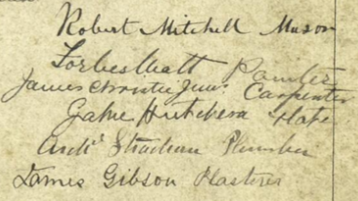

Signatures-of-Tradesmen-working-on-Banff-Library-and-Museum

A. Lyon

A. Lyon