By eye-witness Anne

It was just a normal Saturday for me. My mother woke me up in time for my school hockey match – a home game against Fraserburgh Academy. I struggled out of bed and looked sleepily out of the window. Dark clouds were scudding across the sky and rivulets of rain trickled down the windowpane. Not a day for hockey or football but, unless the visiting teams had phoned to cancel the fixture, their hired bus would already be on its thirty mile journey to Banff Academy. I would have to turn up at the school in order to find out.

Standing at the unsheltered bus stop, with the wind whipping around my legs and the rain soaking my thin trench-coat, I was sure that the whole thing would have been called off. But as I rushed up the school brae, I saw, to my horror, a blue Alexander’s bus sitting at the gate. Our opponents had arrived! “The match is off” was the cry, as I staggered into the cloakroom. Our teachers had apparently decided that even we hardy northeast scholars could not be expected to play football and hockey in such weather. That was a relief! The not-so-good news was that there had been no time to cancel our school lunch, which was an integral part of the sporting arrangements in this rural part of the world. After all, we sometimes had to travel forty miles or more to our matches, and a school dinner was part of the deal.

It was probably a mistake to make us hang around just for the sake of a school lunch. But the food had been bought, the cook had arrived and it seemed the sensible thing to do. How were our teachers to know that an extremely deep depression situated off the coast of Norway was rapidly heading our way? Our school hall was completely surrounded by classrooms and, in this cosy cocoon, we entertained our visitors while the meal was being prepared. It wasn’t until we ventured out to the canteen that the full force of the storm hit us. We hastily gobbled up our mince and tatties, gathered our things together and set out for home.

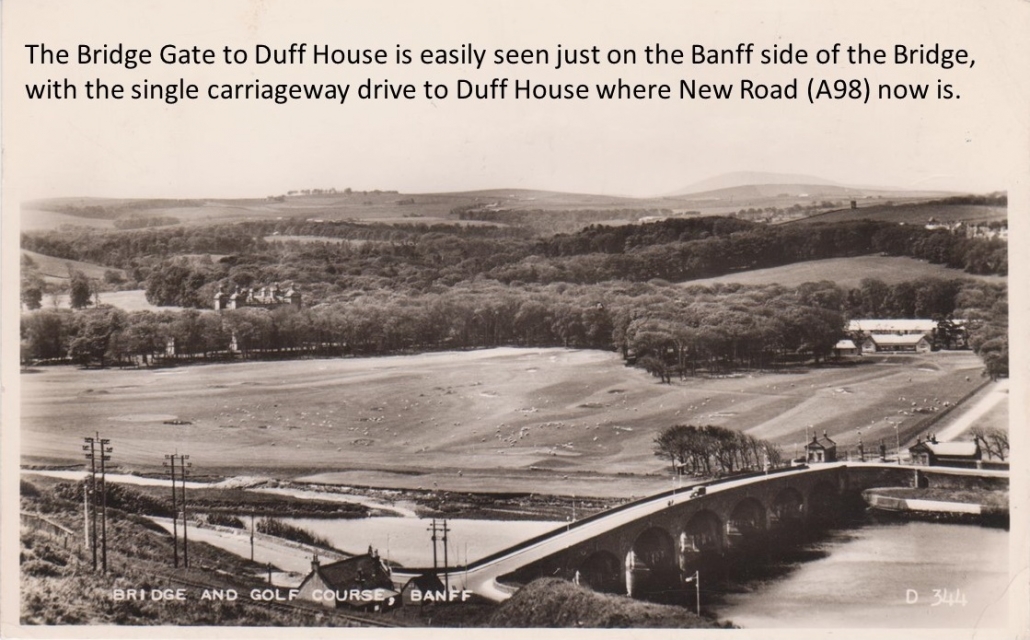

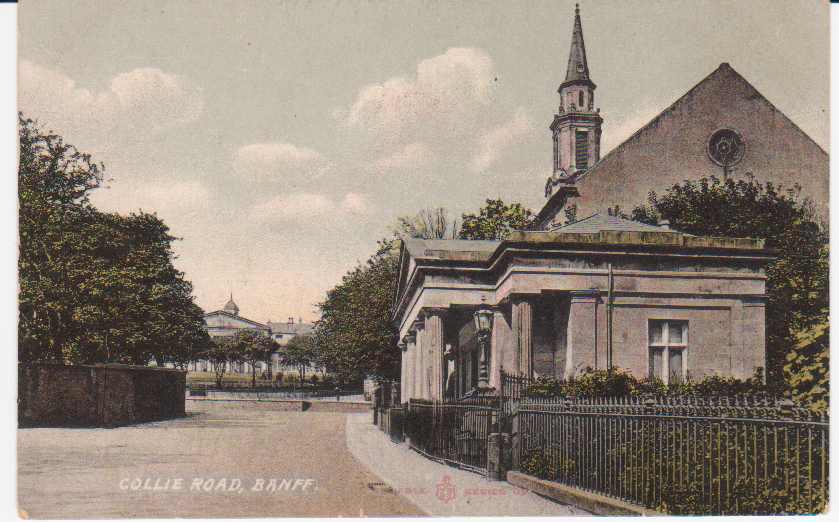

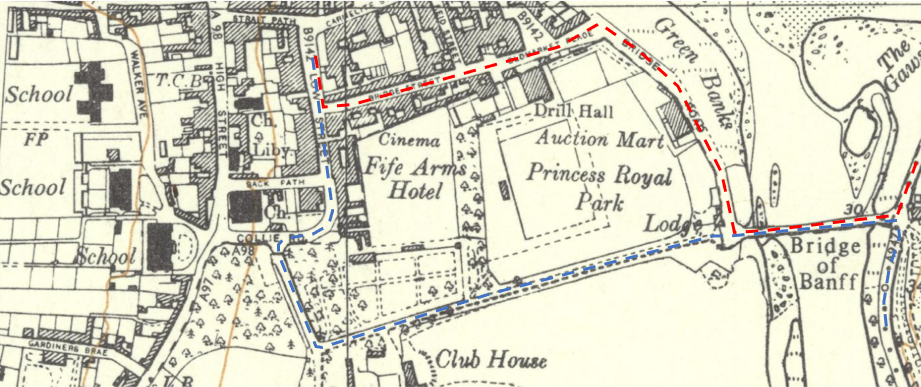

My friend and I raced down to the ‘Plainstones’ to catch the 12 o’clock bus. Wet and windblown, we sank into our seats; but our relief was short-lived. The bus driver didn’t appear to be taking his usual route. The river Deveron had burst its banks, he explained, and he would have to take us through the private grounds of Duff House.

The caretaker at the lodge opened the big wrought-iron gates for us and we headed for the bridge over the already swollen river. We should have turned left along the coast road but huge waves, created by the wind and exceptionally high tide, were crashing over the sea wall and rebounding off the steep hillside at the opposite side of the road.

Instead we turned right along the ‘Howe’, a tree-lined country road popular with Sunday strollers. Not today, though! The wind screeched through the bare branches of the birches, beeches, elms and rowans, bending them over until they were almost horizontal. We crouched in our seats, terrified that, at any moment, a tree might get uprooted and come crashing down on top of us. Once the driver had negotiated the corner at the cemetery, we knew we were out of the woods and that home was only a few minutes away.

My mother wasn’t too surprised when the electricity went off in mid-afternoon. “Power cables”, she said – in a knowledgeable sort of way. At teatime, the gas for the cooker fizzled out as well. Only a few years after my mother had acquired her fancy new domestic appliances, we were plunged back into the middle ages, with only a few candles and a coal fire for comfort. At bedtime, I had to find the way to my attic room in the dark. The wind was still rattling the panes of the dormer window and I pulled the covers over my head to shut it out.

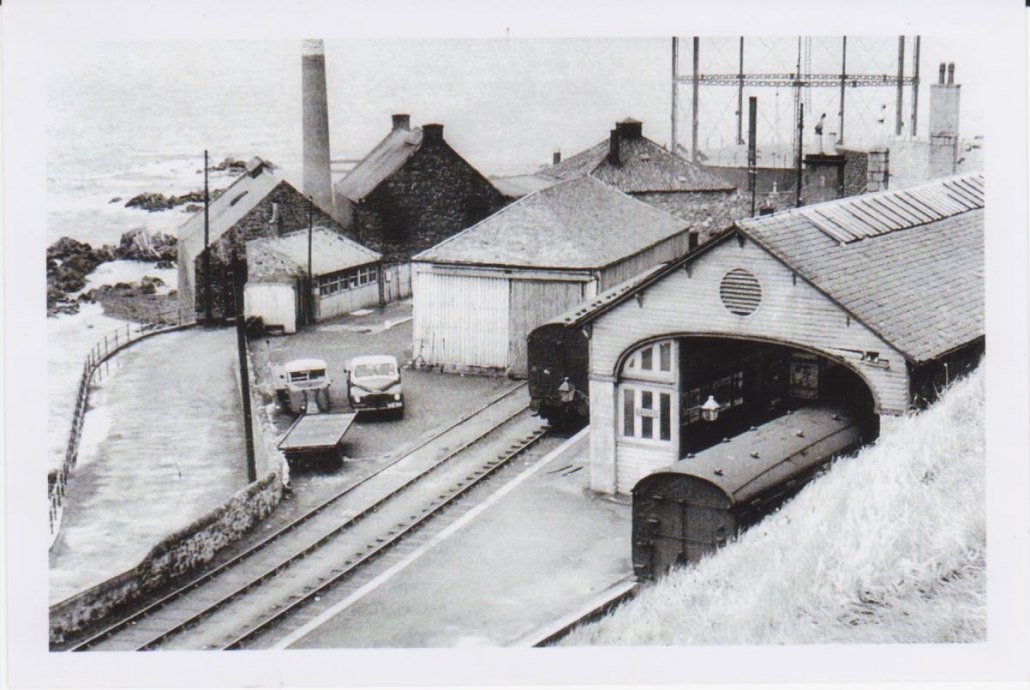

Sunday morning brought a curious calm. Under a pale grey, watery sky, we ventured out to inspect the damage. At the harbour, almost half the town seemed to be staring in bewilderment at a fishing boat sitting lopsidedly in the middle of the street. Further along the road, the sea had completely undermined the foundations of the petrol station, which now dangled precariously on the rocks. And the coastal road, which we should have travelled along the day before, resembled a boulder field.

It is the custom for people to be drawn together at such times, united in commiseration or in simple curiosity. And so, small groups of local folk were dotted here and there along the sea-front, viewing the devastation with disbelief. On our meanderings, we discovered that the gasometer in Banff had been washed into the sea, which explained our lack of gas.

I also met some of the football boys, who had missed the last bus out of Banff at lunchtime on Saturday. They had apparently decided to walk back home and had been forced to struggle over the Hill O’Doune to escape the rising tide. Crawling on hands and knees, clinging on to bushes and to each other, they managed to avoid being blown away and reached the relative safety of Macduff with nothing more than a few scratches and a thorough soaking.

By evening the electricity supply had been restored but, with no prospect of gas in the forthcoming weeks, my mother’s shiny ‘New World’ cooker now supported a pair of decidedly ‘old world’ Primus stoves. With our immediate needs taken care of, our thoughts now turned to the outside world. We had been cut off from the rest of civilization for two whole days and we had no idea how the rest of Britain had fared.

It was Monday morning before we became aware of the full impact of the storm. Newspapers and radio reported that; in East Anglia, 2,500 square miles of land lay under water and 307 people had perished in the floods at King’s Lynn; one sixth of the Netherlands was also under water with more than 2000 lives lost. In the south-west of Scotland, 133 people had been drowned when the British Rail ferry, Princess Victoria, had sunk in Belfast Lough on her crossing from Stranraer to Larne. Much closer to home, six men of the Fraserburgh lifeboat drowned when their boat was caught by a giant wave and capsized at the harbour mouth. The seas were so fierce that it was impossible for any of the witnesses to enter the sea to rescue them. For us and others around Britain, the forces of nature had taken their toll.