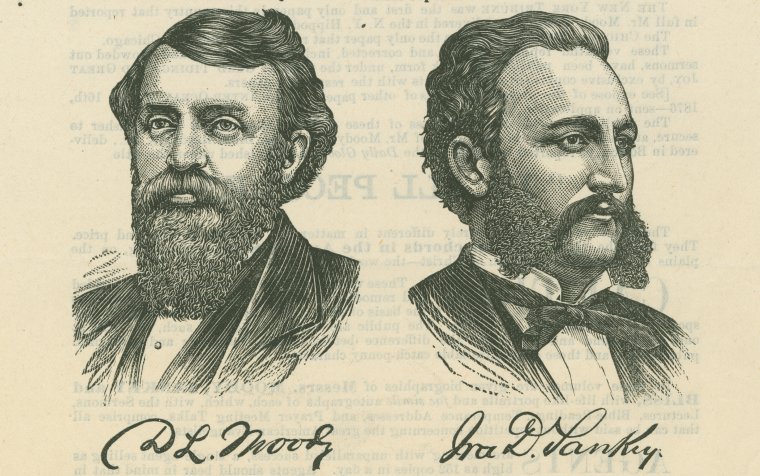

Recently, reading a local diary yet to be published, the writer makes an observation about his day of Sunday 2nd August 1874: “pretty well churched today”! In all the writer had attended five services that day, three in Banff, one in Macduff, and one in the open air in the Duff House Park. This “revival” was due to a mission to the area by two American evangelists, Dwight Moody and Ira Sankey. Mr Moody was the preacher and Mr Sankey was reported as an especially good singer. The visit is also referred to in the biography of the Rev Bruce of Banff.

Combining these two sources it seems the visit started with a service in Banff Parish Church. As their skills as orators and singers had been widely broadcast since they had been in Edinburgh and then Glasgow for over 3 months, it seems the church was packed out – more than packed out as “half of them did not get in”. In the afternoon Sankey gave a recital, but there were so many people that most “heard little of him” – plus the fact it was a really windy day!

Then it was back to Banff Church, before going to Duff House Park. At that time the grounds to the north of Duff House – between the House and what is now New Road, but then was the private Duff House drive – were more open; there was no golf course and less trees, so perhaps it was here that the assembly was held. Fifteen thousand people are said to have attended.

And once again back to the church. Rev Bruce describes Mr Sankey’s singing as having a “sweetness of the fine baritone voice, combined with a certain manliness of tone and look, simply overpowered the people. My choir broke down and could not sing… The whole congregation were so subdued that we called on two members to offer up short petitions, and then Mr Sankey sang his second solo:

There were ninety and nine that safely lay,

In the shelter of the fold,

But one was out on the hills away,

Far off from the Gates of Gold.

Away on the mountains wild and bare,

Away from the tender Shepherd’s care.”

Rev Bruce had never in his life seen “a congregation so swayed and moved, liked a field of corn beneath a breeze of wind.” “We remained for five minutes in silent prayer and then recovered ourselves.” One or more of the above services (although definitely not the morning one which was definitely in the “established” church) or perhaps during the following week, was also held in the Trinity Church, then a Free Church – now part of the River Churches.

Andrew Taylor

Andrew Taylor © The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum