From 1702 until 1815, the French and British were involved in six wars. In the wars, merchant ships suffered heavy losses off of the North East coast. The merchant ships were attacked by privateers of mainly French origin, although privateers of American and Dutch origin were active too.

Privateers were privately owned ships, commissioned by governments to attack the merchant shipping of enemy countries and disrupt their trade. The fate of ships captured by privateers varied – their cargoes and the ships themselves could be sold, refitted or burnt. Often their crews were allowed to return home. The Moray Firth was a busy shipping route at this time as ships would sail around the top of Britain to avoid trouble in the English Channel.

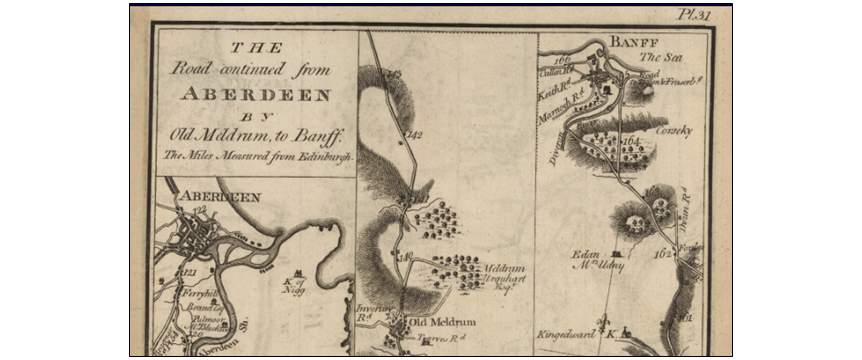

The most noted incident was in 1757. On the 5th of October, Francois Thurot, in command of the frigate Marischal de Belleisle and several other ships, appeared in Banff Bay, much to the distress of the people of Banff. The plan seemed to be to invade Banff, plunder and destroy it with a force of 1100 men. The people of Banff were saved though, by a storm, a gale which forced the ships to cut their cables and flee.

In 1777 the Tartar of Boston, an American privateer, captured Lord Fife’s ship – the Anne of Banff – (amongst others). Lord Fife feared he would not be safe living at Duff House “We shall be burnt and plundered”

By 1781, in response to the threat, a very fine battery of 9 eighteen pounders were erected at Banff above the high ground above Banff harbour. This is where the name Battery Green comes from. As well as this soldiers were stationed along the Moray Firth coast.

Ultimately, the focus of transport shifted from the sea to overland routes and led to the building of the first bridge at Banff.

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB