Arthur Duff of Orton was the youngest son of William Duff, 1st Earl Fife, and is buried in the Duff House Mausoleum. He was beloved by all and has a bridge and chapel built in his memory.

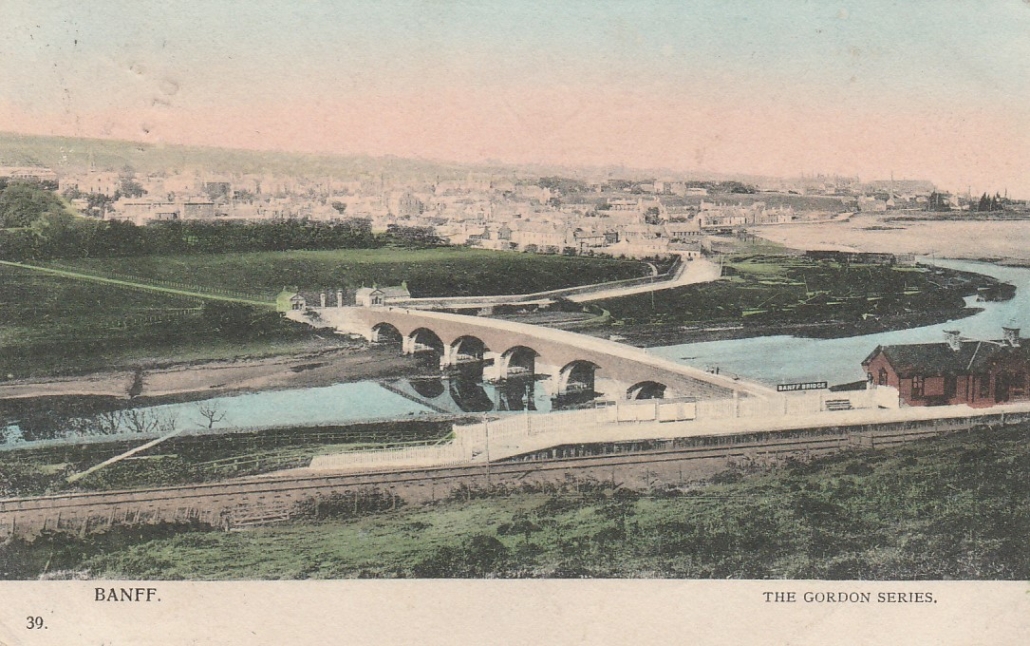

Today the River Deveron heads in a fairly straight line into Banff Bay, but it used to divert west and run along the sea wall of what is today Deveronside, in 1906 nearly destroying some properties.

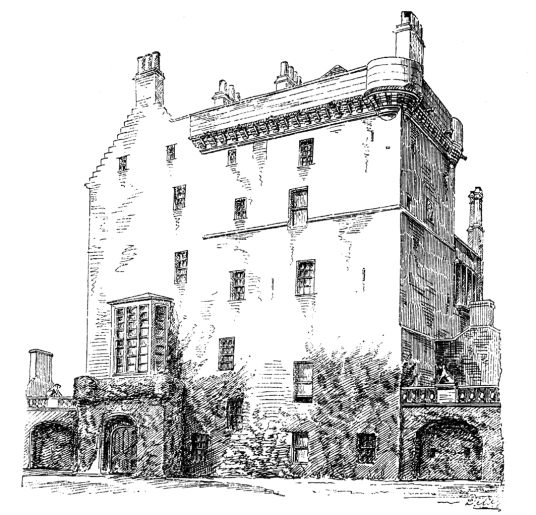

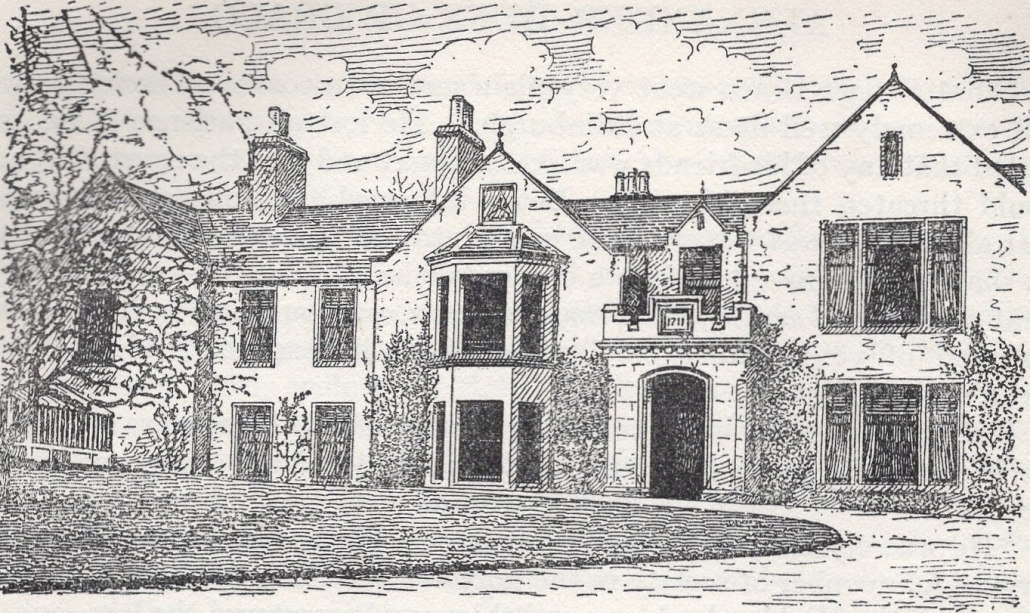

The First Earl Fife who had Duff House built but never lived in it, instead used Rothiemay House as his main residence. He developed and extended both the House and particularly the grounds, as is shown on General Roy’s Map of 1747.

As with many other families he had many children, 14 of them, seven sons and seven daughters. The seventh offspring, the fourth son, was named George. He was educated in Edinburgh and then St Andrews. He had two years from the age of nineteen in the 10th Regiment of Dragoons but had been given education by his father with a commercial future in mind.

Shortly after leaving the Dragoons he married Frances Dalzell, daughter of General Dalzell; apparently they kept the marriage secret for several months but the Duff family letters don’t give a clue as to why. George lived in London for many years because Frances didn’t want to come to Scotland!

They had four children, the youngest of which was Frances; she was born 26th June 1766 in Elgin. She became the “family pet” and while her mother may not have liked Scotland, “Little Fan” was mostly brought up by her paternal grandmother, Lady Fife, wife of the First Earl, at Rothiemay. A painting of Rothiemay House was made in 1767, much as Little Fan must have known it.

Little Fan seemingly was a very beautiful, well mannered and agreeable child; but she was a delicate child, even catching smallpox at one time, and in 1777 had jaundice. The letters indicate that her appetite was always small. In various letters she is referred to not just as “Little Fan” or “Lady Fan”, but even as “Miss Monkey”. Her uncle Arthur (son of William, First Earl Fife) was a particular favourite and they frequently corresponded, but Little Fan was clearly much admired, even by a previous handmaid of the Countess (Little Fan’s grandmother) who wrote “a charming and young creature”.

We know of at least two suitors; “Bob” who has not been traced, and also James Urquhart, but nothing was to become of these as she suddenly died, aged just 20, on 6th March 1787. Although initially interred at Grange (near Huntly) she was moved to the Duff House Mausoleum – perhaps because she was a family favourite.

Since the early 1800’s the Duff family have had a connection with Argentina, and specifically since 1824 so has the town of Banff, through giving the Freedom of the Town to José de San Martin, a friend of the 4th Earl Fife. While José visited James in Banff, James never travelled to Argentina. As far as can be found the first Duff to visit Argentina was James’ brother, Alexander Duff in 1807. Alexander was brought up in Banff, and currently rests, with his wife, in the Duff House Mausoleum.

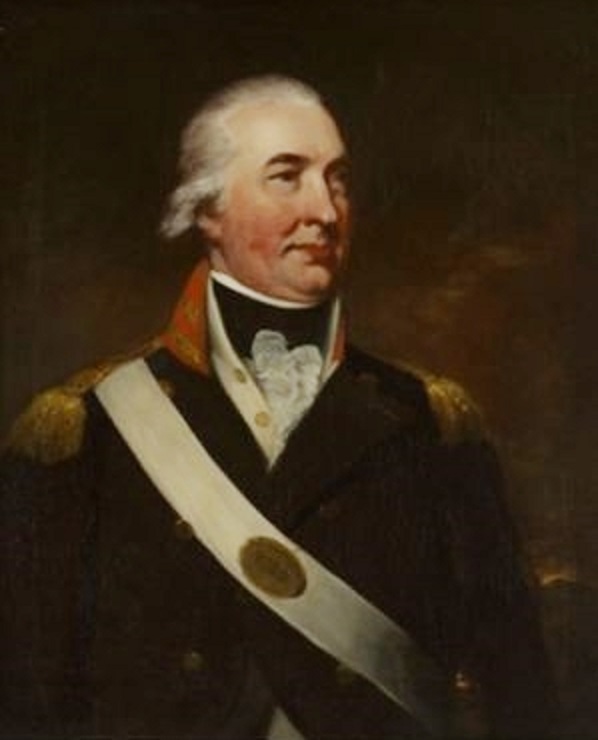

Alexander, born 1777, was the second son of the 3rd Earl Fife, and as was quite common, as a second son his career was probably always destined for the army. The 2nd Earl brought both brothers – his nephews – to Banff for their initial education (see also “Duff House’s Own Local Hero”), firstly at Duff House, but then with Dr Chapman at Inchdrewer.

In May 1793 Alexander joined the Army as an Ensign at the age of sixteen, joining the 65th Berkshire Regiment at Gibraltar. In 1794 he was promoted to Lieutenant and the next year to Captain in the 88th Regiment (the Connaught Rangers). With the 88th he served in Flanders and in 1798 was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel at just 21 years old. He served in the East Indies and Egypt, taking part in the capture of Alexandria. In 1806 he was part of the force that took control of Montevideo as part of the British aim to gain a part of the riches in South America, by wresting some areas from the Spanish. In 1807 he was commanding one of three columns which landed in Buenos Aires, but due to the poor tactics of General Whitelocke, later court-martialled due to his incompetence, he surrendered before reaching his objective of reaching the Great Square. No censure was placed on Alexander, and he was promoted full Colonel, then Major General in 1811.

He was clearly a capable and well-liked officer as reported in several accounts. In 1821 he was promoted to Lieutenant-General, and full General in 1839. He was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Hanover in 1833 – the same as his older brother James 4th Earl Fife had received in 1827. King William IV knighted Alexander in 1834.

General Sir Alexander became the local Member of Parliament from 1826 to 1831 continuing the family practice, although his first attempt in 1820 failed by one vote, and nearly resulted in civil insurrection between the Duff and Grant supporters in the town of Elgin – fortunately defused by Lady Anne Seafield (on the Grant side) by sending her 700 clansmen back to the Highlands.

Alexander’s home was Delgaty Castle, part of the family estate at the time. In 1812 he married Anne Stein, and had five children. The oldest died at just a few months old, but James, born 1814, became 5th Earl Fife when Alexander’s brother, James 4th Earl, passed in 1859. Their fifth child, born 1824, they named Louisa Tollemache – an unusual Christian name; whether this was in memory of her uncle’s late wife’s family, the Tollemache’s of Helmingham in Suffolk, has not been confirmed (James 4th Earl had married Mary Manners, the daughter of Lady Louisa Tollemache and John Manners, who died in 1805 – see “Duff House’s Own Local Hero”).

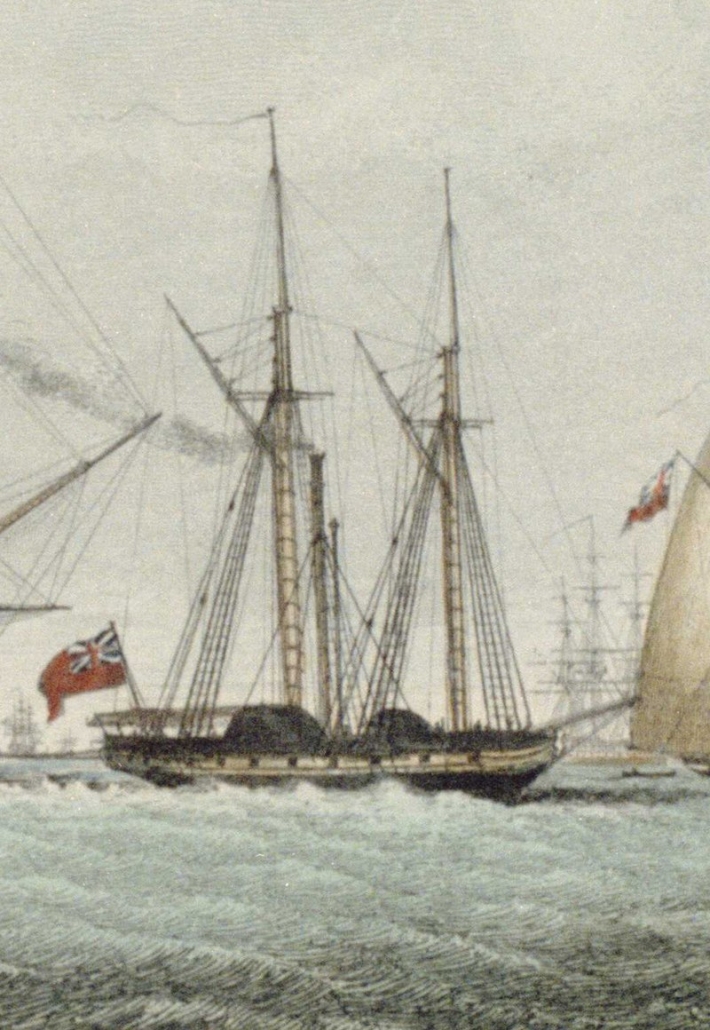

In 1851 Alexander passed away in London, but his body was transported to Banff on HMS Lightning to be interred in the Duff House Mausoleum; Anne, his wife, was also interred there 8 years later.

For interest, the HMS Lightning was one of the first steam warships in the Royal Navy, 126 foot long, driven by side paddles, launched in 1823 and in service until the late 1860’s. She must have been quite a sight coming into Banff Bay. There is a detailed model of her is in the Royal Museums Greenwich.

A rare photo came to light recently showing some members of a Brass Band, partly in uniform, in the grounds of Duff House. With the kind assistance of Gavin Holman who has extensively researched early Brass Bands throughout the UK, as well as our own research, we have been able to ascertain that in the last half of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth, four different Banff Brass Bands have been recorded. The first was around 1857/1860 when there was also the Banff Rifle Volunteers Brass Band. Mr Sutherland then organised a Brass Band in 1893, but it seems that was different from the one conducted by Mr R W Hutcheson around 1899. This latter is recorded as parading around the streets of Banff on Hogmanay for the turn of the century – although they did stop for midnight!

But this photo clearly shows the band members in and around a motor car; now identified as a Renault Limousin (there were several models) which were only built from 1912 onwards.

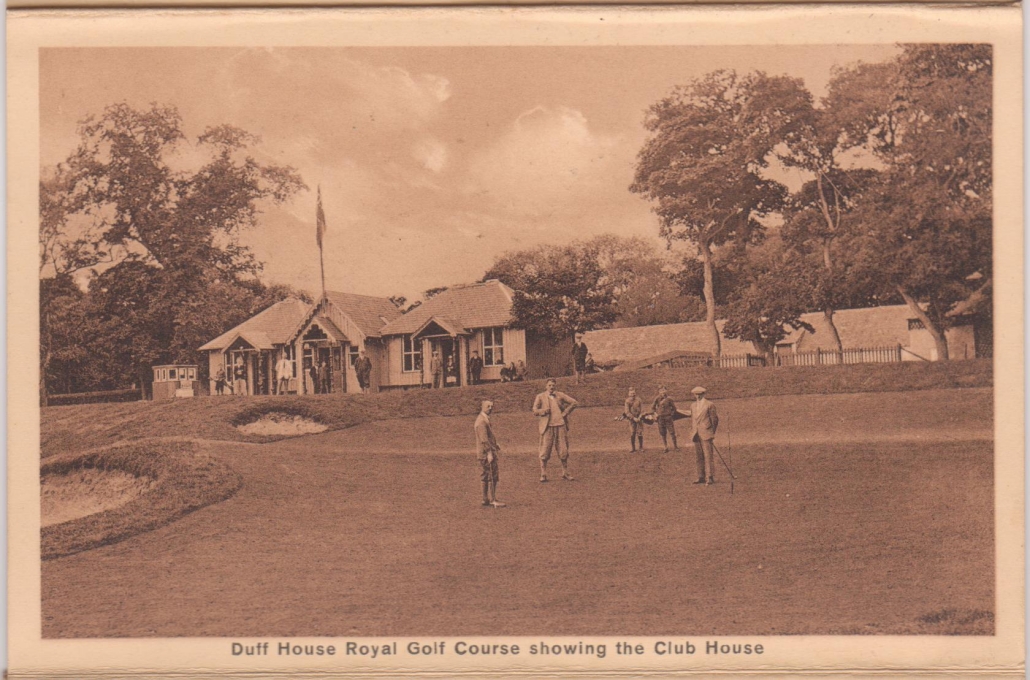

A new Banff Brass Band was formed by Mr Arthur Wilson in the summer of 1913 and it is supposed that this photo must be this band. One of their first engagements it seems was at the Macduff Swimming Gala on Wed 20th July, held of course in the harbour (20 years before Tarlair was built). No doubt they also attended many other local events. They also organised their own dances including at St Andrews Hall. But on Wed 30th July they played at the opening of the new Tea Rooms at Duff House Golf Course on Wed 30th July 1913 (by this time Duff House itself was a Sanatorium); in view of the location of the photo perhaps this is the date of the photo.

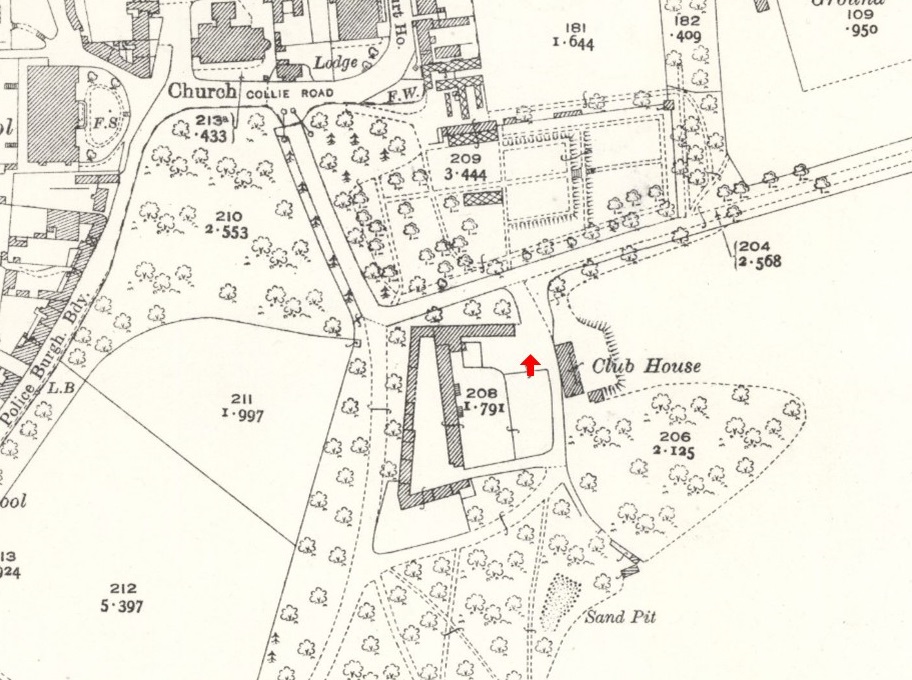

The location is shown on this map by the red arrow.

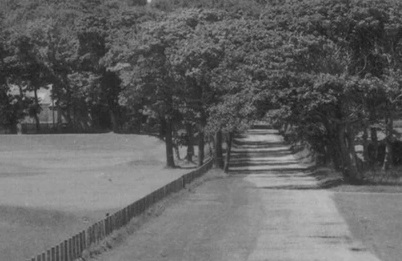

The Vinery can be seen in the photo and on the map, and it is of course more than fifty years before the present “New Road” was built from Banff Bridge to the town. The present road is raised on an embankment, but the original Duff House drive was not, as show in the photo below. The main photo of this Story was taken just to the centre left of this image, looking left to right across the driveway.

The view in the main picture above therefore, looking north, is through gaps in the hedge, to the original Airlie Gardens (as they are known today) as laid out in the 1860’s by Lady Agnes, wife of the fifth Earl Fife, through to the Vinery. The map shows the part of the old Barnyards – the old Duff House stables – that can be seen to the left in the photo. The first Golf Club Pavilion – Tea Rooms? – is out of sight to the right of the main photo. The main photo of this Story was taken towards the centre right of this photo of the Pavilion.

Note: For eagle-eyed readers please note the 1928 OS map as shown above depicts the new Golf Club Pavilion opened in 1926, not the original as in the photo above. It also shows an extra greenhouse in Airlie Gardens built circa 1925, not there in the main photo where the view is right through to the Vinery.

If any reader has any further information, or insights, into this Brass Band or photo, we would welcome them being in touch.

At the present time, in the Grand Salon in Duff House, is a magnificent Christmas Tree, helping to create a festive and relaxed atmosphere within Duff House. Many thanks to the Friends of Duff House.

However it seems it may be only a pale reflection of the tree that stood in the same room 155 years ago, in 1868. This was at the behest of James the 5th Earl Fife and his Countess, Agnes. Not only that, they held a party with numerous guests, in the manner of what was becoming a tradition in Victorian times; those invited were not just the Duff family but all the servants from the House and the estate, including all their wives and families.

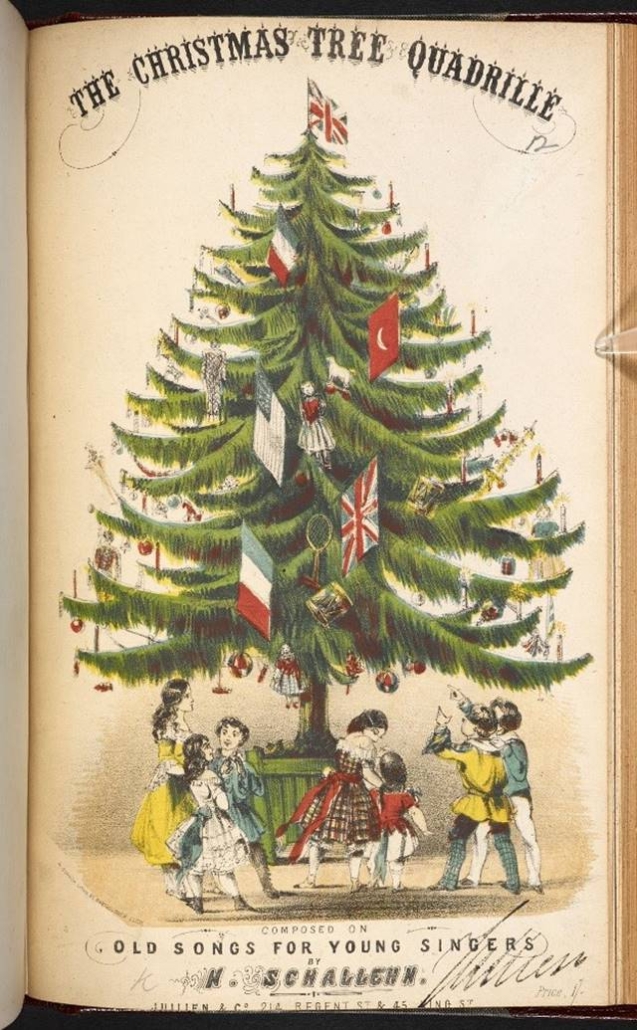

The magnificent and beautiful tree was “prettily decorated with flags and loaded with a multitude of presents”. Having a Christmas Tree was a practice introduced by Prince Albert in circa 1840, bringing the tradition of several decades from his native Germany. The drawing above of the Royal Family’s Christmas Tree was published in 1848 in the Illustrated London News – the first known picture of a Christmas Tree in the UK. The idea quickly caught on around the country.

The inclusion of flags as part of tree decorations was not just a Duff House practice at the time, but is illustrated on this cover below from the 1860s. The Duff family was clearly right on trend!

Music for the occasion was provided by Lady Alexina Duff, aged 17 at the time, on a harmonium; and some solos were sung by one of the servants.

But what made the occasion so special it seems, was the effort taken by Lady Agnes and three of her daughters, Anne, Alexina and Agnes (it seemed they liked names beginning with “A”, also having an Alice and Alexander – later the 6th Earl Fife and first Duke of Fife!) to choose presents for each of the individuals at the party, all piled high under the tree. Each present was wrapped – a practice introduced from America in the 1850s, and each had a name on it – one for every guest. The servants got dresses or articles of clothing, children had toys or books all chosen specifically for the person; “not a few of the presents were valuable and costly” said the Banffshire Journal.

Then there was a sumptuous supper served (not sure by who!) and at midnight Lord Fife gave a speech. The news he gave was that he, his wife and son, Lord Macduff, loved living at Duff House and would spend as much time there as they could – which was greeted by cheers and applause. He also gave the news that an extension would be built on the west side of Duff House, with the work starting in February 1870 – the wing that we now know was bombed in 1940 and no longer exists above ground (except for the war memorial).

In the Duff House Mausoleum, just inside the door, is a list of who in 1912 was believed to be buried in the crypt. This includes four people who do not have the surname of Duff – instead “Tayler” (the “e” is not a mis-type!).

This name Tayler was introduced to the Duff family when the elder daughter, Jean or Jane Duff, of the 3rd Earl Fife married William Alexander Francis Tayler in 1802. As close relatives – Jane’s older brother James became the 4th Earl Fife – they were given Rothiemay House to live in. This building had a fire in 1964 and was demolished, although the gatehouse and some other buildings remain. This is a 20th century photo of Rothiemay House; the feature picture is at is was in the mid nineteenth century – much as Lady Jane Tayler would have known it.

During her life Jane was held in much esteem by the locals around Rothiemay but also in Banff where they were frequent visitors. As evidence of how much she was liked her obituary recalls that “her kindness was not occasional, or by fits and starts, but perennial”. The Banffie wrote “she has gone – and will be missed by many, but the good she has done will live after her, and there will be many hereafter to speak – and the witness is on high – of the good deeds and alms which she did”.

The four Taylers at rest in the Duff House Mausoleum are:

The Honourable, the Lady Jane Tayler, died 22 May 1850

Alexander Francis Tayler, died Sep 1854 (husband)

Alexander Tayler, died 26 Jul 1809, age 6 (son)

Alexander Francis Tayler, died 8 Nov 1828, age 14 (son)

Jane and Alexander had six other children as well as the two above, although it seems they were beset with problems.

- The first born, Alexander, died in an accident at Duff House on the day of the birth of his brother, William. Alexander was pushing amongst adults trying to see his new brother and a unfortunately knocked him and he feel into a bath of boiling water. He survived a few days but his injuries were too severe;

- Anne, the second born, also died in an accident but it’s nature is not known;

- William, born 1809 at Duff House, later in life married his cousin Georgina, granddaughter of Captain George Duff (see the Story on this website entitled “Trafalgar”). Two of their children became celebrated as historians of the Jacobites and the Duff family itself (Henrietta and Alistair), and the oldest as an accomplished artist;

- Jane Marion born 1810 died 1869;

- James George born 1811 died 1875;

- Alexander Frances (in the Mausoleum) born 1814, died 1828 of measles;

- George Skene, born 1816 became a Commander in the Royal Navy, died 1894;

- Hay Utterson, born 1819, died 1903.

The two children in the Mausoleum were born deaf and dumb, as was Hay the youngest. This seems to have been a sad inheritance from their great grandmother, Mary Forbes, but does not seem to have re-occurred.

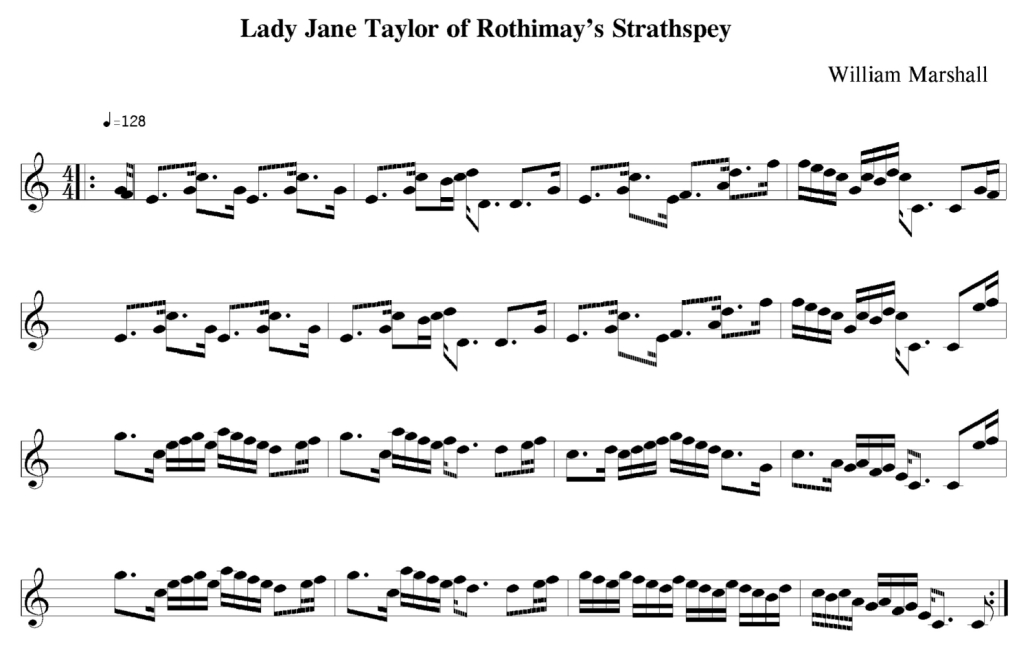

Alexander and Lady Jane were very well connected around the area, not only with the local population around Rothiemay, but elsewhere because of their family connections. There are many newspaper reports of them attending events in Banff in the first half of the nineteenth century. They were very much part of the gentry and mixed accordingly. One little piece of evidence of this is that William Marshall, one of the greatest composers of Scottish fiddle music, named one of his 257 tunes after her; no doubt heard in Rothiemay and Banff:

This Story was written while looking out the window at a wet and windy day. Almost 149 years ago to the day, there was an even worse storm, described nationally as a hurricane.

A Banff eyewitness described it as “Most awful rough day, a real hurricane and raining too”.

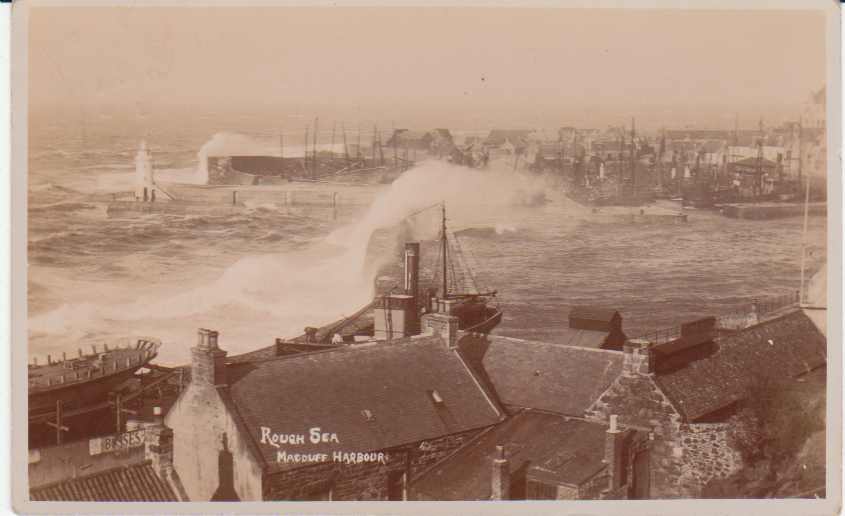

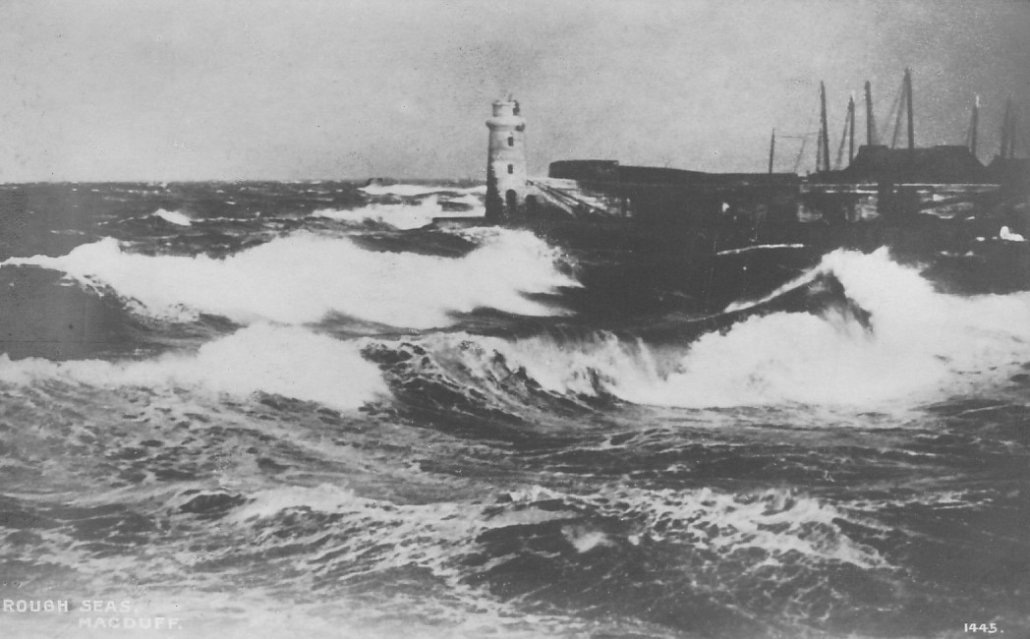

This photo was taken after 1903 (when the Macduff Harbour lighthouse was put in its present position) but does show a rather rough sea, something that most people in Banff and Macduff will have seen!

The Banffshire Journal reports “the gale commenced very suddenly, about nine o’clock. The wind had been from the south, and, in a very short time, veered round to west-north-west. The sea was very disturbed, and the rain and spray, blown from the crests of the waves, shortened the range of vision seawards.”

Various damages were reported. It was apparently difficult to walk outside, but also unsafe to walk the streets due to the “quantity of slates falling off the roofs of houses”. Various chimney cans were thrown down, and some of the older and more exposed houses in Banff were “a good deal damaged”, and many had water damage from the force of the wind pushing rain inside. A number of trees were blown over, especially reported in Duff House woods.

In 1874 the Bar of Banff was still in place, ie the sand and gravel bank sticking out from the Macduff side of the river mouth, and the sheltered area south of it was used for beaching boats. The wind blew over several herring boats that were on Green Banks, but they were not badly damaged. These nineteenth century pictures show the Bar with some herring boats sheltering (there are some just north of Banff Bridge, on the Green Banks side, in the hand water-coloured picture)

Sometimes of course larger ships like this schooner were beached for repairs, or for building, on Green Banks.

From the national newspapers of the time it seems Banff and Macduff did not get the worst of the weather; further south in places there was more substantial damage. It is reported that every telegraph wire north of Birmingham was out of action!

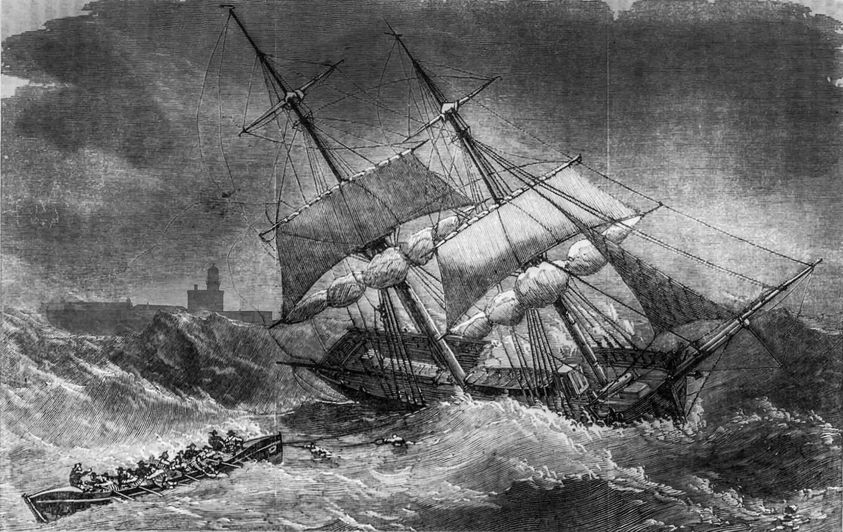

Fraserburgh did have a wreck, of the schooner “Moir”. Her details are not known, but she had sailed from Portsoy with a cargo of oats, bound for Newcastle. But she was blown on to Fraserburgh Sands (just south of the town). Captain James Smith and his crew were saved by the Fraserburgh Lifeboat “Charlotte”. The painting below was done in 1875, the year after, but it is not specified as the “Moir”. The black and white image shows the “Charlotte”, again in action in 1877 for another schooner, the “Fuchsia”, a rescue which saved 4 adults and 4 children.

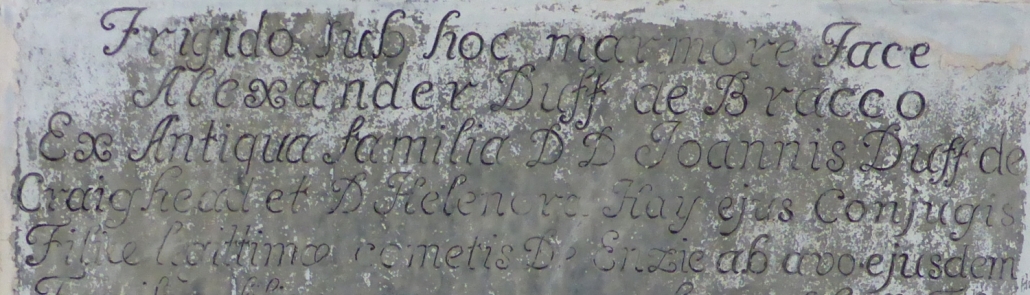

Inside Duff House Mausoleum, one of the memorial stones – now a bit damaged by age – seems to include the word “Antigua”. Some of the wording is very difficult to read so there are no real clues as to what the connection of the Duff family to the Caribbean might be!

In fact this is the Memorial for Alexander Duff of Braco, the uncle of the first Earl Fife. The memorial reads:

“Frigido sub hoc marmore Jace Alexander Duff de Bracco ex antiqua familia D D Joannis Duff de Craighead …..” which translated makes it clear it is nothing to do with the Caribbean!:

“Under this cold marble lies Alexander Duff of Braco of the old family of John Duff of Craighead….”

ie the word is “Antiqua” not “Antigua”, a “q” not a “g”. It certainly isn’t obvious because an upper case A is used, and the q looks almost identical to the g that has been incised except for a small squiggle at the top!

After the 2nd Earl Fife had the Mausoleum built in 1792, initially to house his parents who had first been buried at Rothiemay, before he moved them to the lovely Mausoleum spot above the river, he also moved other relatives. Alexander Duff of Bracco (or Braco) was his great uncle and one of the key members of the Duff family who built up their fortune. He was born in 1652 and died in 1705 and originally buried in Grange, but not before he had bought many estates across north east Scotland.

Alexander is very important in the history of Macduff. In 1699 Alexander purchased “Doune” (ie Macduff after it’s name was changed in 1783). The seller was Lord Cullen – not part of the Seafield family of Cullen House, but Sir Francis Grant, a Scottish Judge who later became Lord of Monymusk.

Alexander Duff of Braco married Margaret Gordon in 1678, and they had four daughters and one son, William of Braco born circa 1685. William died in 1718 with one daughter, also Margaret, so on his death his estate passed to the crown (by way of escheatment, there being no valid direct male descendants). His uncle, William Duff of Dipple, proved he was the male heir and so William of Braco’s estate passed from the Crown to him. William Duff of Dipple was the father of the first Earl Fife. (As an aside to this main story, being family orientated, William Duff of Dipple signed Eden House and estate, just south of Banff, over to Margaret Duff, his nephew’s daughter, so that her future was secure.)

In other words, without Alexander Duff of Braco purchasing Doune/Macduff, it would not have passed via his son and uncle, and in turn to William Duff 1st Earl Fife, who built Duff House, and then to his son James Duff, 2nd Earl Fife. It was James Duff 2nd Earl who developed Doune from being a fishing hamlet to being the town it is today, bringing in craftsmen, building the harbour, the roads, the bridge and much more.

So “Antigua” is not a Caribbean link, but part of the history that has resulted in the great town of Macduff!

For clarity on some of the places:

Craighead was used as an alternative name for Muldavit, today in Rathven (just N or the A98 just before you get to the first Buckie turning from the east). Neither name appears today, but Craig Head on the coast is still named on maps, west of Findochty.

Braco is a place; a farmhouse, in Grange, east of Keith. The “Book of the Duffs” shows Braco in circa 1912 after it had been updated from Alexander Duff’s time, and Google Streetview shows it in 2021.

Dipple is a place, a farmstead, just south of Fochabers. William of Dipple, who’s son became 1st Earl Fife of Duff House, was a brother to Alexander of Braco.

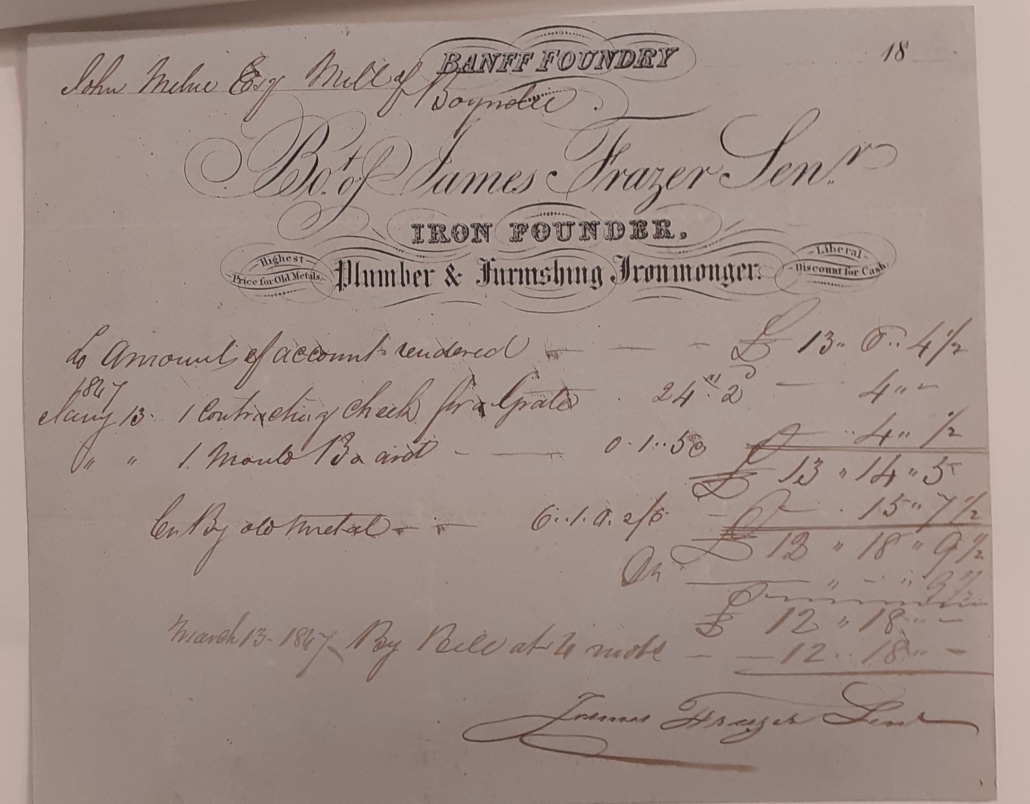

A Banff Foundry crest on a gatepost in Banff

An Invoice from James Fraser, Banff Foundry, 1800s

Chapel on the corner of Carmelite Street and Reid Street, with the Foundry area behind it.

If you look carefully as you walk around Banff you can still find traces of a major industry in the town (see the photos).

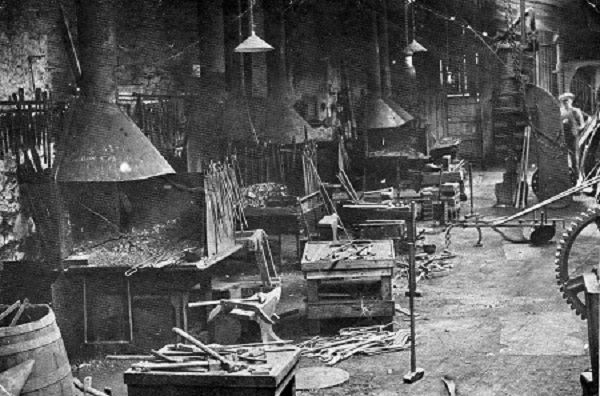

The area where Tesco supermarket is now would have been very different before 1955. Banff Foundry was developed on the site of a blacksmith’s forge (Robert Thomson’s blacksmith shop), bounded by Reid Street, Carmelite Street and Bridge Street. The industrial forge was installed in 1827 by William Fraser.

In 1858, an article in the Banffshire Journal and Advertiser gave details about the new Foundry and the iron-making process.

“The large new casting room is 60 feet long by 30 feet wide”. “The furnace is like a huge lemonade bottle, from which a chimney to a considerable height rises. On the side, and near the head of the furnace, at a spot exactly corresponding with that on which the aerated water vendor pastes his label, is a large circular opening, opposite which a platform is extended. From this platform the workmen (who must partake, somewhat of the salamandrine character from the amount of heat they endure) feed the furnace, by the opening, with metal and fuel.” (Banffshire Journal and General Advertiser, Tuesday 23 November 1858)

The Foundry made a wide range of agricultural implements, gates, fences etc. Many people collect old agricultural implements made in Banff by G. W. Murray and later Watson Brothers, which can still be seen today. (See the accompanying photos.) Around Banff, there used to be drain covers with Banff Foundry written across them.

In 1867 to 1869, the Foundry is described in the Ordnance Survey name book as “A large iron foundry on Reid Street, occupied by G W. Murray, the property of the Aberdeen Town & County Bank.”

G.W. Murray was the owner of the Foundry from 1863 until his death in 1887, aged 53 years. He had an adventurous life, living in Australia from 1852 until 1862, where he made his fortune. (Australia’s gold rush started in 1851). George Wilson Murray married Cecilia Blake in 1862 and built the Italianate house at South Colleonard, just outside Banff.

The Foundry had a tumultuous history, burnt down in 1892. However, it recovered very quickly and the business thrived, employing 35 people in the 1890s.

In 1902, the Foundry, then being run by the Watson brothers, exported agricultural machinery worldwide, e.g. Cape Colony, South Africa; Montevideo and Hobart, Tasmania, being just a few of the destinations.