The historic buildings of Banff all tell a story. It could be of the trades and crafts once carried out in the town, it could be of the families that once lived there. One building that tells the story of a revolution is the former Trinity and Alvah Church in Castle Street, now used by the Riverside Church.

This building is a monument to the people of the disruption of the Church of Scotland in 1843. On 14th May 1843, the Reverend Francis Grant preached for the last time in the Parish Church and led the dissenters from the church. At first they leased Seatown chapel, now demolished.

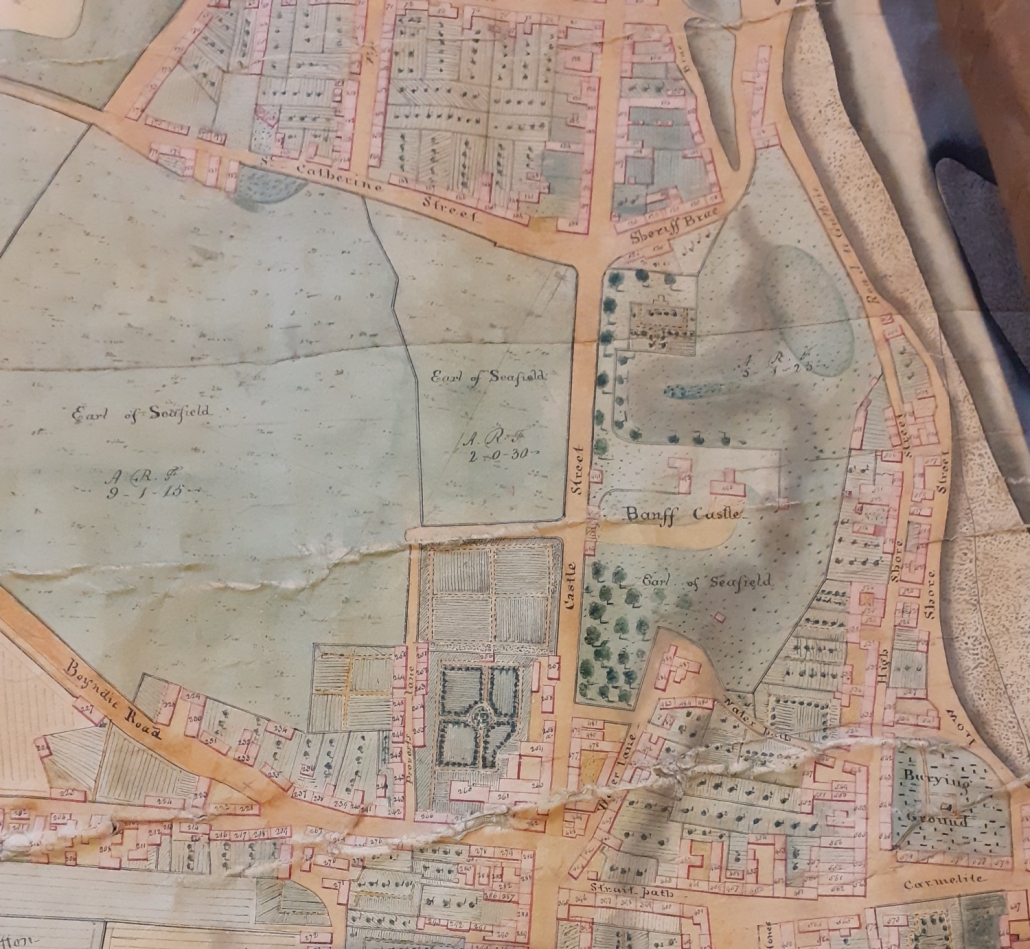

The dissenters engaged James Raeburn, architect, from Edinburgh, but born in Boyndie, to draw up plans for a new church, on a site on the new South Castle Street that was being laid out at the time.

In a letter from James Raeburn on 16th May, 1843, promising a plan and sketch of the Free Presbyterian Church to be erected in Banff James Raeburn stated “I have kept in view comfort, strength and cheapness, even in the exterior arrangement.“ “I also approve of you adopting stone, rather than wood which will in the end be less expensive as well as more durable”

Donations to build the church came in from all over the country and in all amounts – varying from a few shillings to several pounds. E.g. Mr Lillie from Nottingham – 10/-, Mr James Wood – £5. The people who paid for the church were from all walks of life.

The foundation stone of the new church was laid in August 1843, along with 111/2 d. The new church was opened in June 1844. A Day school was added next to the church in 1844 at a cost of £250 and in 1845, the manse was built at a cost of over £500. The church was enlarged in 1877 at a cost of £1500.

Trinity and Alvah church was built in the Ionic style, one of many designed by James Raeburn for the Free Church in 1843, is considered an unusually grand example of a Free Church.

South Castle Street in 1866

South Castle Street in 1826