Arthur Duff of Orton was the youngest son of William Duff, 1st Earl Fife, and is buried in the Duff House Mausoleum. He was beloved by all and has a bridge and chapel built in his memory.

A rare photo came to light recently showing some members of a Brass Band, partly in uniform, in the grounds of Duff House. With the kind assistance of Gavin Holman who has extensively researched early Brass Bands throughout the UK, as well as our own research, we have been able to ascertain that in the last half of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth, four different Banff Brass Bands have been recorded. The first was around 1857/1860 when there was also the Banff Rifle Volunteers Brass Band. Mr Sutherland then organised a Brass Band in 1893, but it seems that was different from the one conducted by Mr R W Hutcheson around 1899. This latter is recorded as parading around the streets of Banff on Hogmanay for the turn of the century – although they did stop for midnight!

But this photo clearly shows the band members in and around a motor car; now identified as a Renault Limousin (there were several models) which were only built from 1912 onwards.

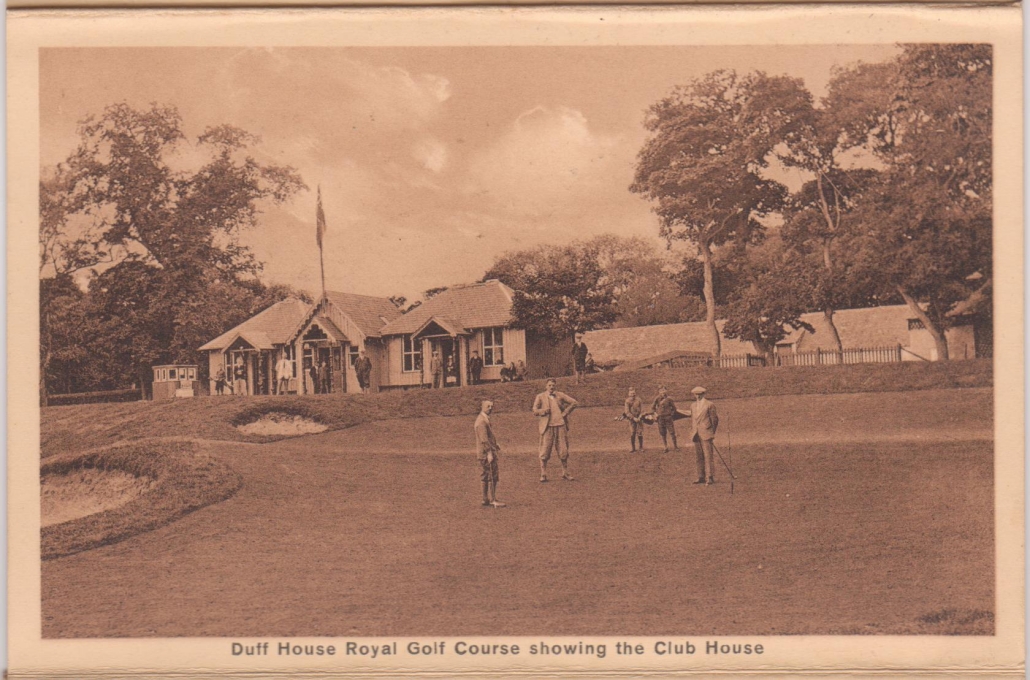

A new Banff Brass Band was formed by Mr Arthur Wilson in the summer of 1913 and it is supposed that this photo must be this band. One of their first engagements it seems was at the Macduff Swimming Gala on Wed 20th July, held of course in the harbour (20 years before Tarlair was built). No doubt they also attended many other local events. They also organised their own dances including at St Andrews Hall. But on Wed 30th July they played at the opening of the new Tea Rooms at Duff House Golf Course on Wed 30th July 1913 (by this time Duff House itself was a Sanatorium); in view of the location of the photo perhaps this is the date of the photo.

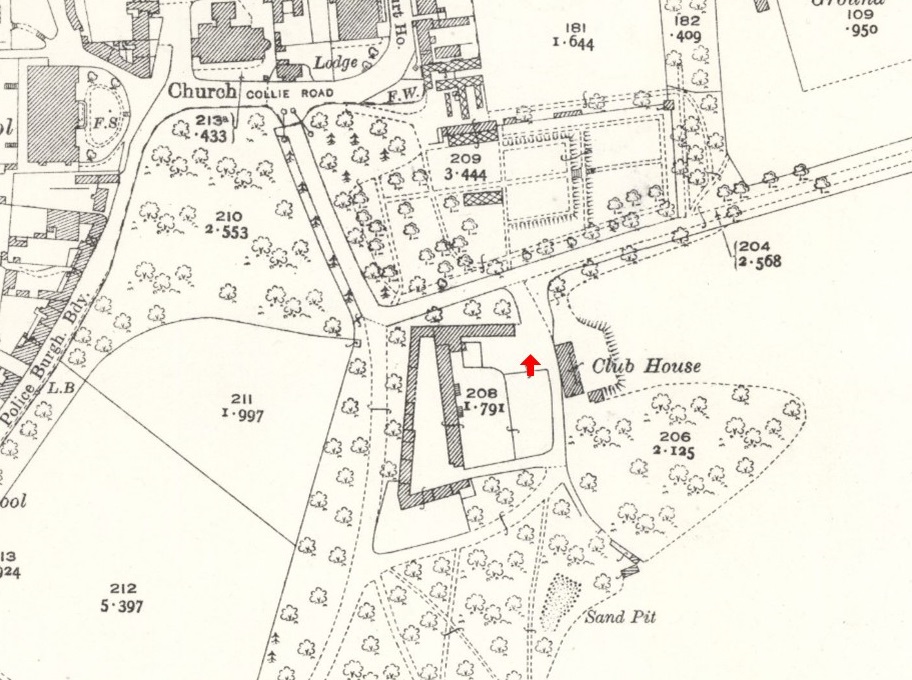

The location is shown on this map by the red arrow.

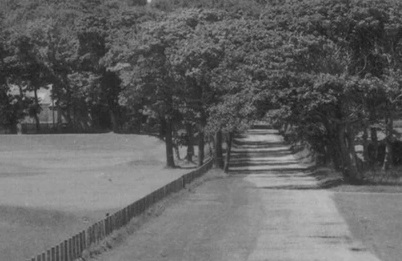

The Vinery can be seen in the photo and on the map, and it is of course more than fifty years before the present “New Road” was built from Banff Bridge to the town. The present road is raised on an embankment, but the original Duff House drive was not, as show in the photo below. The main photo of this Story was taken just to the centre left of this image, looking left to right across the driveway.

The view in the main picture above therefore, looking north, is through gaps in the hedge, to the original Airlie Gardens (as they are known today) as laid out in the 1860’s by Lady Agnes, wife of the fifth Earl Fife, through to the Vinery. The map shows the part of the old Barnyards – the old Duff House stables – that can be seen to the left in the photo. The first Golf Club Pavilion – Tea Rooms? – is out of sight to the right of the main photo. The main photo of this Story was taken towards the centre right of this photo of the Pavilion.

Note: For eagle-eyed readers please note the 1928 OS map as shown above depicts the new Golf Club Pavilion opened in 1926, not the original as in the photo above. It also shows an extra greenhouse in Airlie Gardens built circa 1925, not there in the main photo where the view is right through to the Vinery.

If any reader has any further information, or insights, into this Brass Band or photo, we would welcome them being in touch.

At the present time, in the Grand Salon in Duff House, is a magnificent Christmas Tree, helping to create a festive and relaxed atmosphere within Duff House. Many thanks to the Friends of Duff House.

However it seems it may be only a pale reflection of the tree that stood in the same room 155 years ago, in 1868. This was at the behest of James the 5th Earl Fife and his Countess, Agnes. Not only that, they held a party with numerous guests, in the manner of what was becoming a tradition in Victorian times; those invited were not just the Duff family but all the servants from the House and the estate, including all their wives and families.

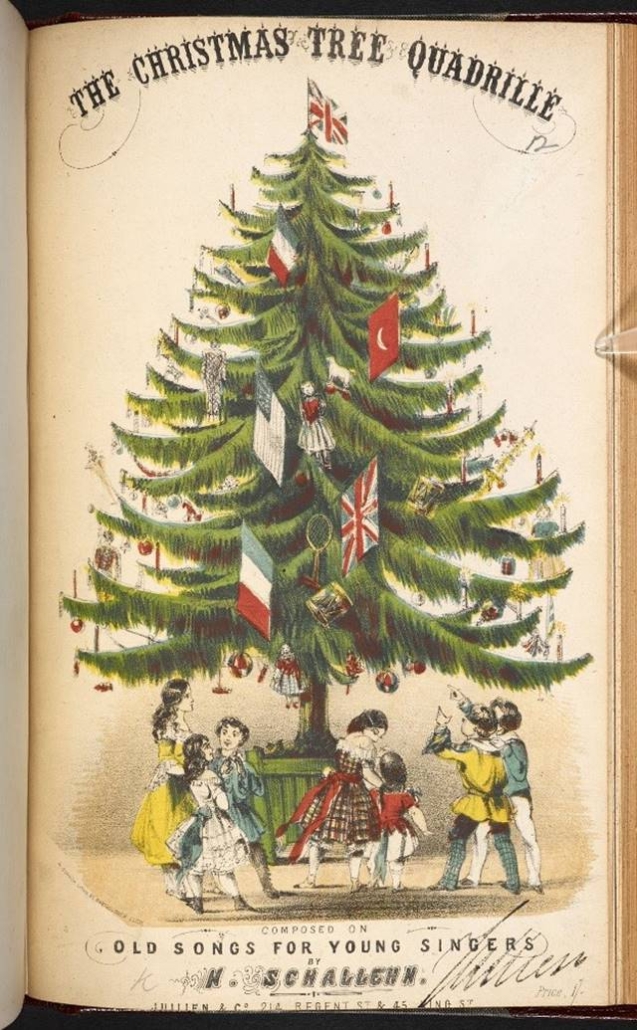

The magnificent and beautiful tree was “prettily decorated with flags and loaded with a multitude of presents”. Having a Christmas Tree was a practice introduced by Prince Albert in circa 1840, bringing the tradition of several decades from his native Germany. The drawing above of the Royal Family’s Christmas Tree was published in 1848 in the Illustrated London News – the first known picture of a Christmas Tree in the UK. The idea quickly caught on around the country.

The inclusion of flags as part of tree decorations was not just a Duff House practice at the time, but is illustrated on this cover below from the 1860s. The Duff family was clearly right on trend!

Music for the occasion was provided by Lady Alexina Duff, aged 17 at the time, on a harmonium; and some solos were sung by one of the servants.

But what made the occasion so special it seems, was the effort taken by Lady Agnes and three of her daughters, Anne, Alexina and Agnes (it seemed they liked names beginning with “A”, also having an Alice and Alexander – later the 6th Earl Fife and first Duke of Fife!) to choose presents for each of the individuals at the party, all piled high under the tree. Each present was wrapped – a practice introduced from America in the 1850s, and each had a name on it – one for every guest. The servants got dresses or articles of clothing, children had toys or books all chosen specifically for the person; “not a few of the presents were valuable and costly” said the Banffshire Journal.

Then there was a sumptuous supper served (not sure by who!) and at midnight Lord Fife gave a speech. The news he gave was that he, his wife and son, Lord Macduff, loved living at Duff House and would spend as much time there as they could – which was greeted by cheers and applause. He also gave the news that an extension would be built on the west side of Duff House, with the work starting in February 1870 – the wing that we now know was bombed in 1940 and no longer exists above ground (except for the war memorial).

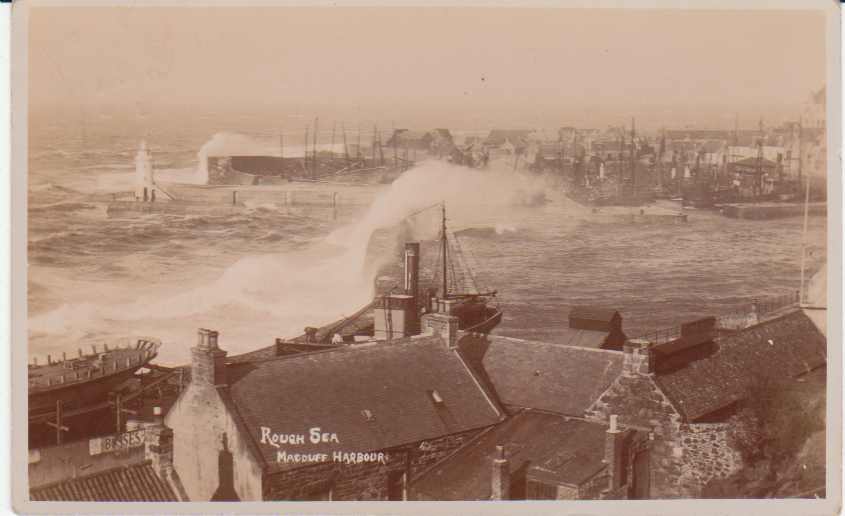

This Story was written while looking out the window at a wet and windy day. Almost 149 years ago to the day, there was an even worse storm, described nationally as a hurricane.

A Banff eyewitness described it as “Most awful rough day, a real hurricane and raining too”.

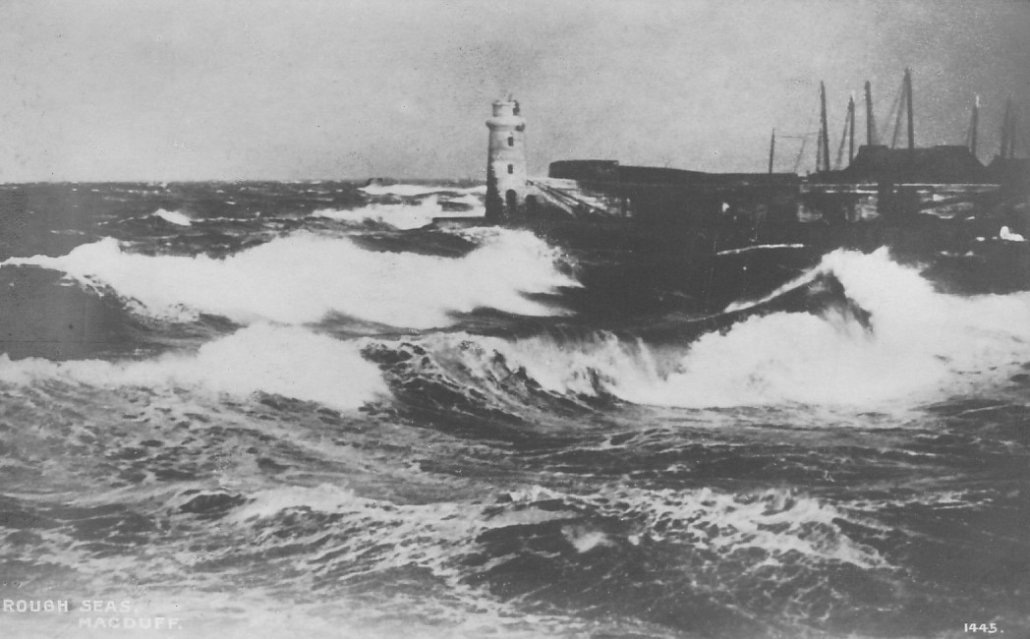

This photo was taken after 1903 (when the Macduff Harbour lighthouse was put in its present position) but does show a rather rough sea, something that most people in Banff and Macduff will have seen!

The Banffshire Journal reports “the gale commenced very suddenly, about nine o’clock. The wind had been from the south, and, in a very short time, veered round to west-north-west. The sea was very disturbed, and the rain and spray, blown from the crests of the waves, shortened the range of vision seawards.”

Various damages were reported. It was apparently difficult to walk outside, but also unsafe to walk the streets due to the “quantity of slates falling off the roofs of houses”. Various chimney cans were thrown down, and some of the older and more exposed houses in Banff were “a good deal damaged”, and many had water damage from the force of the wind pushing rain inside. A number of trees were blown over, especially reported in Duff House woods.

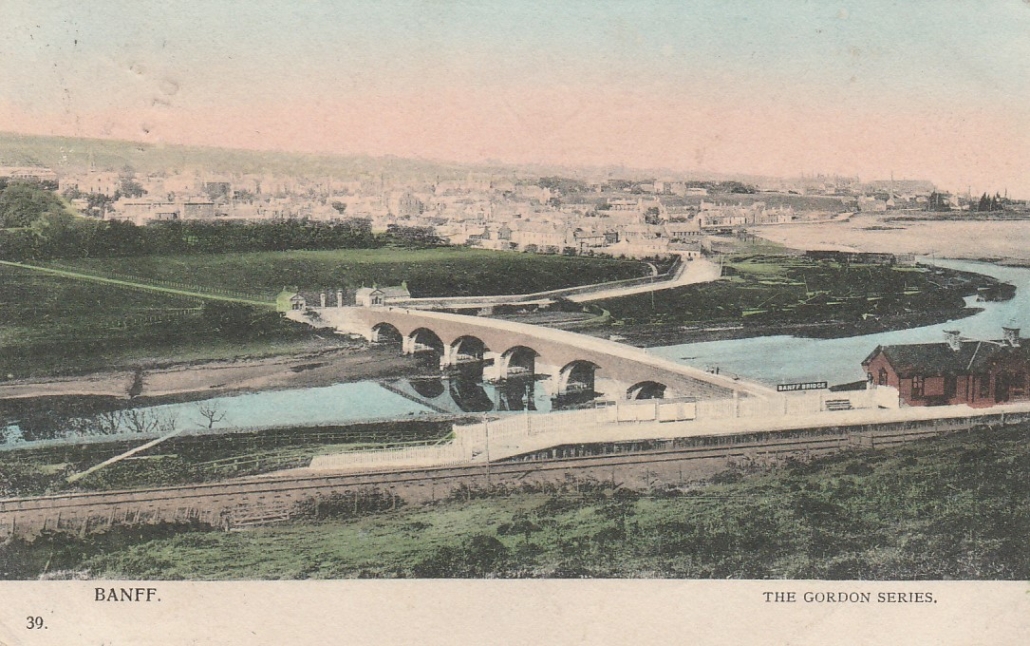

In 1874 the Bar of Banff was still in place, ie the sand and gravel bank sticking out from the Macduff side of the river mouth, and the sheltered area south of it was used for beaching boats. The wind blew over several herring boats that were on Green Banks, but they were not badly damaged. These nineteenth century pictures show the Bar with some herring boats sheltering (there are some just north of Banff Bridge, on the Green Banks side, in the hand water-coloured picture)

Sometimes of course larger ships like this schooner were beached for repairs, or for building, on Green Banks.

From the national newspapers of the time it seems Banff and Macduff did not get the worst of the weather; further south in places there was more substantial damage. It is reported that every telegraph wire north of Birmingham was out of action!

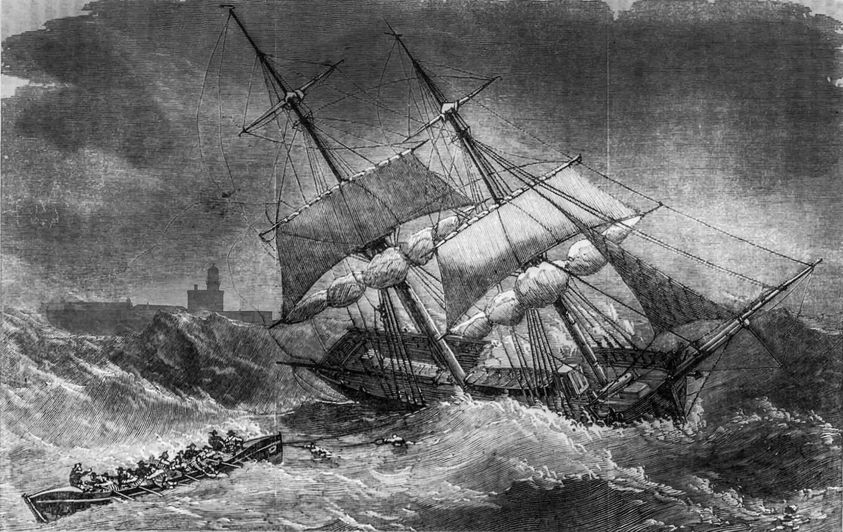

Fraserburgh did have a wreck, of the schooner “Moir”. Her details are not known, but she had sailed from Portsoy with a cargo of oats, bound for Newcastle. But she was blown on to Fraserburgh Sands (just south of the town). Captain James Smith and his crew were saved by the Fraserburgh Lifeboat “Charlotte”. The painting below was done in 1875, the year after, but it is not specified as the “Moir”. The black and white image shows the “Charlotte”, again in action in 1877 for another schooner, the “Fuchsia”, a rescue which saved 4 adults and 4 children.

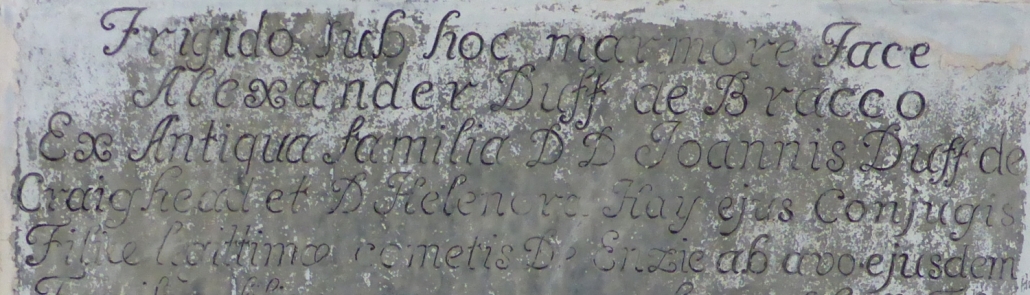

Inside Duff House Mausoleum, one of the memorial stones – now a bit damaged by age – seems to include the word “Antigua”. Some of the wording is very difficult to read so there are no real clues as to what the connection of the Duff family to the Caribbean might be!

In fact this is the Memorial for Alexander Duff of Braco, the uncle of the first Earl Fife. The memorial reads:

“Frigido sub hoc marmore Jace Alexander Duff de Bracco ex antiqua familia D D Joannis Duff de Craighead …..” which translated makes it clear it is nothing to do with the Caribbean!:

“Under this cold marble lies Alexander Duff of Braco of the old family of John Duff of Craighead….”

ie the word is “Antiqua” not “Antigua”, a “q” not a “g”. It certainly isn’t obvious because an upper case A is used, and the q looks almost identical to the g that has been incised except for a small squiggle at the top!

After the 2nd Earl Fife had the Mausoleum built in 1792, initially to house his parents who had first been buried at Rothiemay, before he moved them to the lovely Mausoleum spot above the river, he also moved other relatives. Alexander Duff of Bracco (or Braco) was his great uncle and one of the key members of the Duff family who built up their fortune. He was born in 1652 and died in 1705 and originally buried in Grange, but not before he had bought many estates across north east Scotland.

Alexander is very important in the history of Macduff. In 1699 Alexander purchased “Doune” (ie Macduff after it’s name was changed in 1783). The seller was Lord Cullen – not part of the Seafield family of Cullen House, but Sir Francis Grant, a Scottish Judge who later became Lord of Monymusk.

Alexander Duff of Braco married Margaret Gordon in 1678, and they had four daughters and one son, William of Braco born circa 1685. William died in 1718 with one daughter, also Margaret, so on his death his estate passed to the crown (by way of escheatment, there being no valid direct male descendants). His uncle, William Duff of Dipple, proved he was the male heir and so William of Braco’s estate passed from the Crown to him. William Duff of Dipple was the father of the first Earl Fife. (As an aside to this main story, being family orientated, William Duff of Dipple signed Eden House and estate, just south of Banff, over to Margaret Duff, his nephew’s daughter, so that her future was secure.)

In other words, without Alexander Duff of Braco purchasing Doune/Macduff, it would not have passed via his son and uncle, and in turn to William Duff 1st Earl Fife, who built Duff House, and then to his son James Duff, 2nd Earl Fife. It was James Duff 2nd Earl who developed Doune from being a fishing hamlet to being the town it is today, bringing in craftsmen, building the harbour, the roads, the bridge and much more.

So “Antigua” is not a Caribbean link, but part of the history that has resulted in the great town of Macduff!

For clarity on some of the places:

Craighead was used as an alternative name for Muldavit, today in Rathven (just N or the A98 just before you get to the first Buckie turning from the east). Neither name appears today, but Craig Head on the coast is still named on maps, west of Findochty.

Braco is a place; a farmhouse, in Grange, east of Keith. The “Book of the Duffs” shows Braco in circa 1912 after it had been updated from Alexander Duff’s time, and Google Streetview shows it in 2021.

Dipple is a place, a farmstead, just south of Fochabers. William of Dipple, who’s son became 1st Earl Fife of Duff House, was a brother to Alexander of Braco.

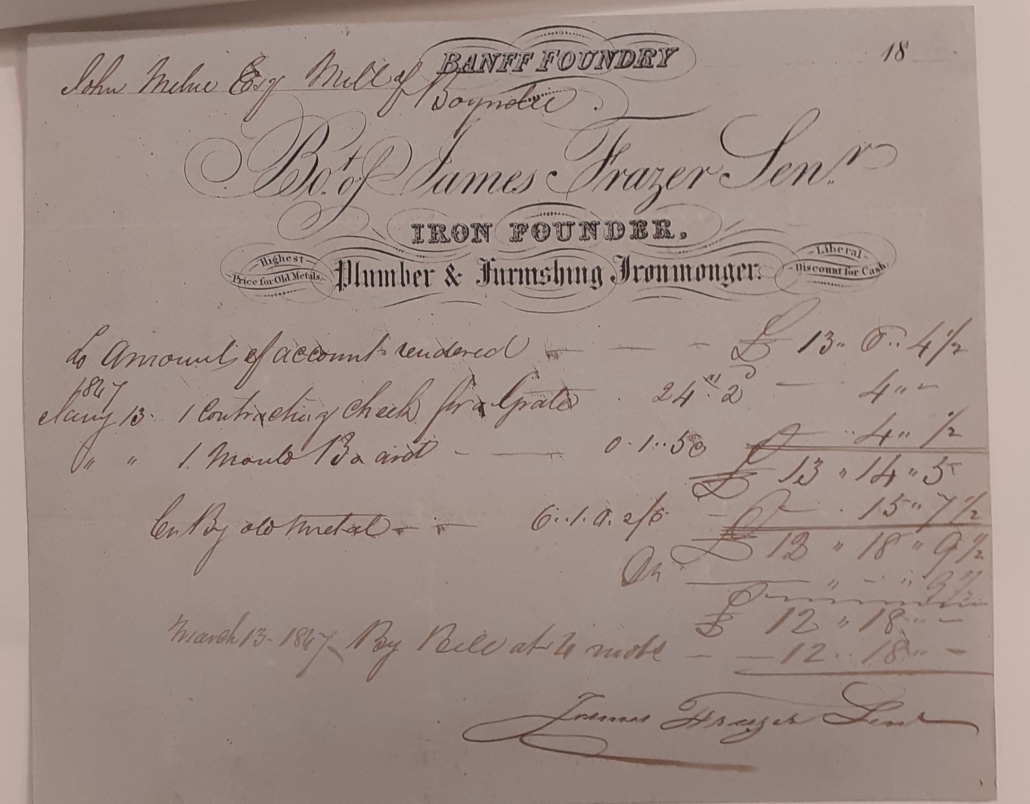

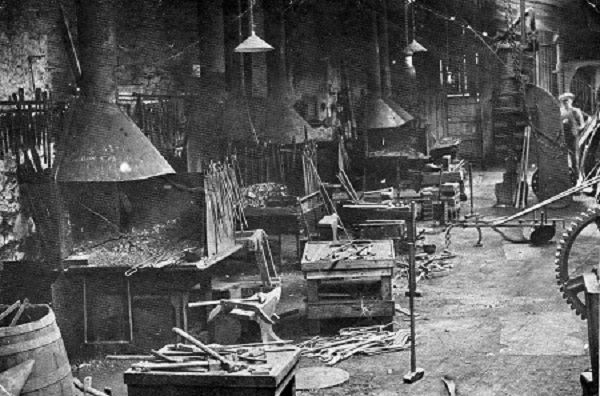

A Banff Foundry crest on a gatepost in Banff

An Invoice from James Fraser, Banff Foundry, 1800s

Chapel on the corner of Carmelite Street and Reid Street, with the Foundry area behind it.

If you look carefully as you walk around Banff you can still find traces of a major industry in the town (see the photos).

The area where Tesco supermarket is now would have been very different before 1955. Banff Foundry was developed on the site of a blacksmith’s forge (Robert Thomson’s blacksmith shop), bounded by Reid Street, Carmelite Street and Bridge Street. The industrial forge was installed in 1827 by William Fraser.

In 1858, an article in the Banffshire Journal and Advertiser gave details about the new Foundry and the iron-making process.

“The large new casting room is 60 feet long by 30 feet wide”. “The furnace is like a huge lemonade bottle, from which a chimney to a considerable height rises. On the side, and near the head of the furnace, at a spot exactly corresponding with that on which the aerated water vendor pastes his label, is a large circular opening, opposite which a platform is extended. From this platform the workmen (who must partake, somewhat of the salamandrine character from the amount of heat they endure) feed the furnace, by the opening, with metal and fuel.” (Banffshire Journal and General Advertiser, Tuesday 23 November 1858)

The Foundry made a wide range of agricultural implements, gates, fences etc. Many people collect old agricultural implements made in Banff by G. W. Murray and later Watson Brothers, which can still be seen today. (See the accompanying photos.) Around Banff, there used to be drain covers with Banff Foundry written across them.

In 1867 to 1869, the Foundry is described in the Ordnance Survey name book as “A large iron foundry on Reid Street, occupied by G W. Murray, the property of the Aberdeen Town & County Bank.”

G.W. Murray was the owner of the Foundry from 1863 until his death in 1887, aged 53 years. He had an adventurous life, living in Australia from 1852 until 1862, where he made his fortune. (Australia’s gold rush started in 1851). George Wilson Murray married Cecilia Blake in 1862 and built the Italianate house at South Colleonard, just outside Banff.

The Foundry had a tumultuous history, burnt down in 1892. However, it recovered very quickly and the business thrived, employing 35 people in the 1890s.

In 1902, the Foundry, then being run by the Watson brothers, exported agricultural machinery worldwide, e.g. Cape Colony, South Africa; Montevideo and Hobart, Tasmania, being just a few of the destinations.

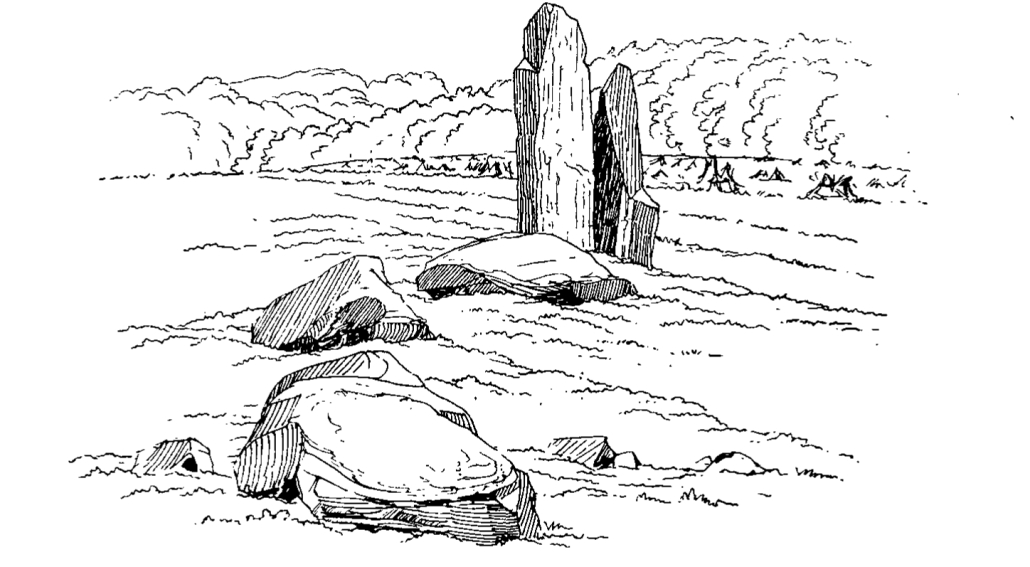

Were humans in Banff and Macduff 3,000 years ago, or even earlier? It seems they must have been and even back then had an appreciation for the beauty of our countryside.

One of the pieces of evidence, about a mile south of today’s Banff Bridge, as a small island in the middle of a large field, there are a few stones, lying at all angles. Today, none can be said to be truly upright.

The first found written record of these doesn’t appear until 1780, described by Thomas Pennant as “several large stone pillars, tending to form a semi-circle, and are doubtless the remains of a Druid temple.” Unfortunately there was no accompanying drawing! The idea of a “Druid” temple, often associated with sacrifices “in honour of immortal gods” was a theory applied to stone circles through to the mid-nineteenth century.

An in-depth survey was conducted in 1903 by Mr Fred Coles and reported in the 1906 Proceedings of the Society of the Antiquaries of Scotland. By this time only two stones were left standing, and an inspection suggested only one of these was in it’s original position – which seems to be the stone most upright today.

Mr Coles concludes that this used to be a recumbent stone circle, ie one stone lying horizontally, with an upright at each end of it – as many such circles can be found in the northeast of Scotland. Unfortunately the Gaveny Brae circle has had stones removed and has been much damaged from “a deplorable want of respect” over the centuries in agricultural districts, a sad fact which Mr Coles much laments.

The position of the site is on a level part of a ridge looking north along the Deveron valley to the Moray Firth – from visiting the site it would seem likely the position was specifically chosen. In 1901 the artist Robert Allan painted the view from seemingly the position of the stone circle, which is very comparable to a more modern view (this one with one stone in shot):

The pillar of smoke or steam just to the right of centre in the Robert Allan painting being a train at Banff Bridge station!

The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland published their detailed review of all the stone circles in north east Scotland in 2011 in their book “Great Crowns of Stone”. By this time the Gaveny Brae stone “circle” is so unlike a circle it is relegated to an eight word reference in “Other Monuments”!

As to the real uses of these “Stonehenges of the north”, perhaps we shall never know. It seems that their use changed over time after being places of worship and sometimes burial sites in the Bronze Age, but less respected as times changed. There is much discussion in the papers of the Banffshire Field Club (available on line) on this subject.

If you are looking to visit the site, on the latest Explorer and Landranger Ordnance Survey maps the Gaveny Brae stone circle is marked as just “Standing Stone”, south of the Distillery; on the previous “1 inch” maps it was labelled “Cairn Circle”, although the obvious mound is believed to be just the result of farming, and not a burial cairn.

On the plus side, at least the Gaveny Brae site is known and marked and visible; another reported stone circle at the top of what is today Strait Path in Banff, the last stone of which was reported as the “Grey Stone”, is supposedly buried beneath the pavement!

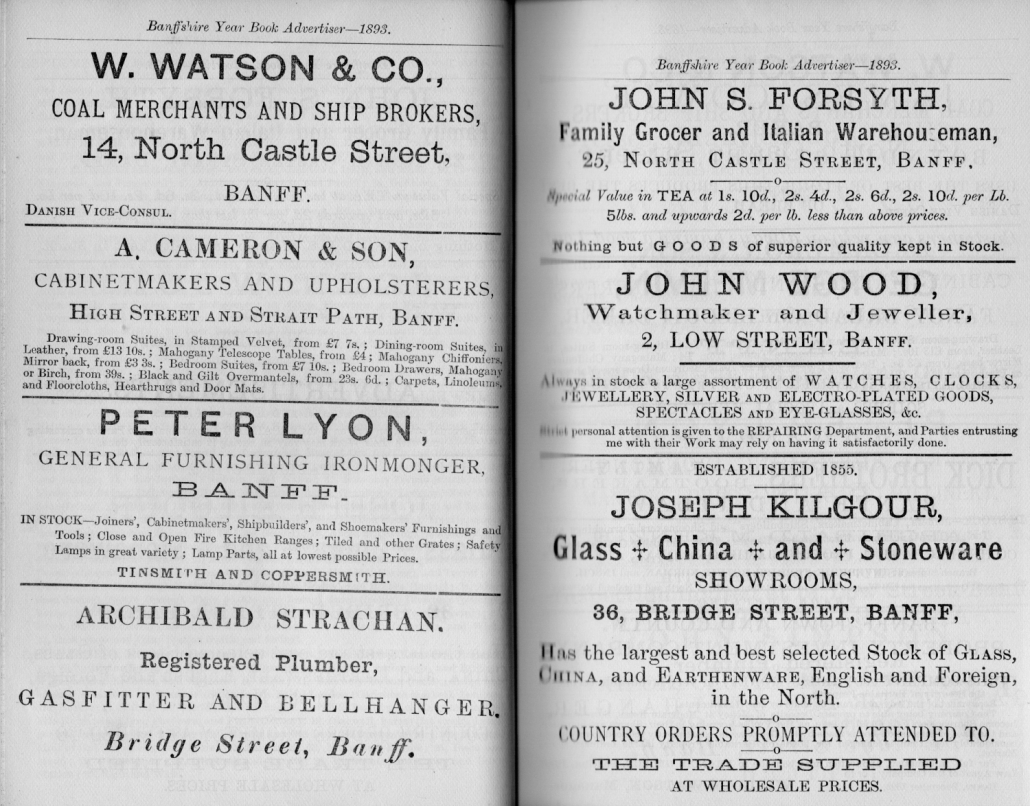

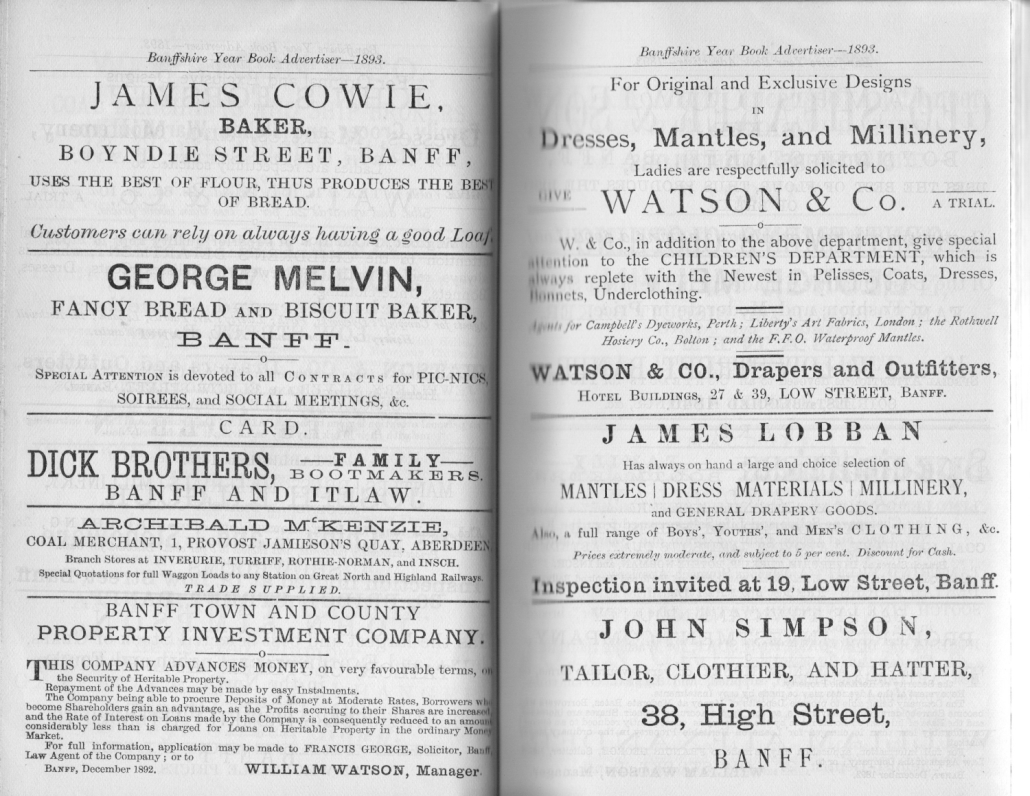

There are six pages of small print about Banff in the Banffshire Year Book of 1893, starting with the unproven fact that it was made a burgh by Malcolm Canmore, who died in 1093. It lists local bequests: “Misses Russell’s bounty provides £12 a year to each of 20 old women belonging to the town”. There was then a Town Council, with a provost, three bailies, a treasurer, a dean of guild, and four councillors, a town clerk and his deputy and a chamberlain. There was a burgh court, and harbour trustees, a school board, and an educational trust. There were two private schools for girls. There were ten solicitors, and five banks. There were six ministers, and they add the officials of the Bible Society, the Young Men’s Christian Association, and the Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society.

How did people spend their time? There was a Literary Society, with a library of 6000 books, a Mutual Improvement Society, there were Science and Art Classes, a choral society, a draughts club, and an amateur dramatic society. If you were energetic, there was a lawn tennis club, a skating and curling club, two cricket clubs, a football club, a fox terrier coursing club, a golf club, and a gun club. There were 104 men in the Rifle Volunteers, and another 73 in the Volunteer Artillery.

There is about half a page of small print on five different categories of freemasons, listing all their officials, the scribe, the inner guard, the sojourner. There were also the United Oddfellows. If you were kindhearted you might help with the dispensary and soup kitchen.

There was a Danish Vice-consul, and they list 25 ships based at Banff. The biggest was the 303-ton Vigilant, the smallest the 16-ton Arab Maid. There is a very complicated list of the last posting time to and from every local hamlet: “Itlaw runner reaches end of walk at 9.35, leaves 12.10 and reaches Banff 2.20pm”.

There is a complete list of the resident Parliamentary voters, all male, of course, all 442 of them, with their trades. By then the franchise was wide enough to include labourers and postboys, several fishermen with ‘tee-names’, and a linen hawker. In the six pages there are women teachers mentioned, and the accompanist to the choral society, but otherwise this seemed a male world.

In 1765 the Kirk Session of Banff gave 10s to Robert Thomson, master of the English School, “to assist in paying the funeral charges of his wife, he being in indigent circumstances”. Their son, George, then 8-year-old, went on to fame, as Robert Burns’ musical partner in collecting Scots songs, and George’s grand-daughter, Catherine Hogarth, was the wife of Charles Dickens.

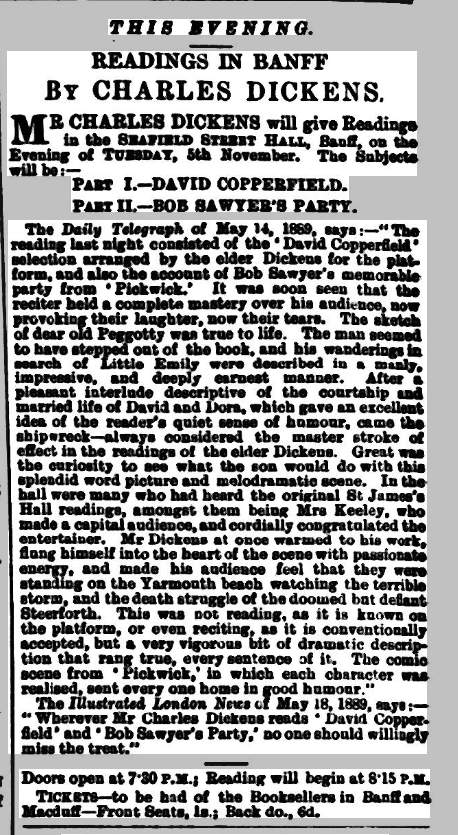

Dickens was a master of words, not only writing them, but aloud, and he made a fortune reading extracts from his novels on the stage. Someone said he did this once in Banff, and I checked, and at once there was this advertisement for a reading by Charles Dickens (see illustration) but it was the wrong man, and twenty years too late. This was his son turning an honest penny. Charles Dickens himself gave a reading in Aberdeen. It was absolutely wonderful if you were near the front of the Music Hall. They had no sound systems in those days.

There were occasional touring theatrical companies, and one of them which came to Banff had Dickens’ Christmas Carol. It wasn’t top of the bill: that was Professor Pepper’s Ghost. The more detailed advertisement for the same show at Peterhead talked about ‘the New and Astounding Effects developed by an ingenious application of the ELECTRIC AND OXY-HYDROGEN LIGHTS’. The audience must have shuddered in delight. There was a Scotch Comic further down the list, and Kool Kennedy (late of Hague’s Minstrels).

But Banff didn’t need Charles Dickens in person, or a touring company. In 1868 ‘a number of gentlemen in the town’ took up amateur theatricals, after a ten-year lapse, and put on the ‘Memorable Trial of Bardell against Pickwick’ from the Pickwick Papers. This was in the St Andrew’s Hall, the Town Hall on the corner. There was a farce as well, which was ‘on the whole, pretty well acted’ which is as near a critical review as the Banffie would dare. They gave a big spread to the story: if only there had been pictures in those days. “The performances reflect very creditably on all who took part in them – whose names, for obvious reasons, we abstain from mentioning.” But if anyone has a picture of their great-great-grandfather as Mrs Bardell, we would be delighted to see it.

William Charles Dawes (1865 – 1920): there is tantalizingly little that can be said with surety about this man. Born in Surbiton, Surrey as the eldest son of four boys to Sir Edwin Sandy Dawes, a ship owner knighted for his contributions to the shipping industry and founder of the ‘Dawes Dynasty’, he will no doubt have had a privileged upbringing and enjoyed the fruits of his father’s labors. Foremost being life at Mount Ephraim, which are now ten-acre gardens open to the public. Picture, if you will, what a delightful childhood that must have been. Consider your own, and the times in which you found yourself playing in your garden, and then transport your younger self into acres of private land characterized by their topiary, arboretum, water and rose gardens. One must wonder at the adventures these four lads undertook on hot summer days and the joy it brought them.

Why did he dedicate a bridge so far north? To proffer a concrete answer would be speculative, but one fact that bears pointing out is that he was married to a woman called Jane Margaret Dawes nee Simpson, and that she was born 1st of september 1869 in Inverboyndie Banff.

It may be a forgivable leap, especially for romantics among us, to suggest it was for his wife’s sake. Anything more than that with so little information on the man available and we would be venturing into conjecture, however. Perhaps the most important thing we can say about him that is not conjectural, is that he was of a noble spirit, as clearly demonstrated by his willingness to pay for the construction of a bridge at Inverboyndie at all.

He died 20th of July, 1920 (19 days after his brother, second youngest, Col. Bethel Martyn Dawes) and is buried in the churchyard of St Michael, Hernhill, Kent, England; thirty-three years later, at the age of 84, his wife was reunited with him in eternal rest.

BPHS

BPHS