Arthur Duff of Orton was the youngest son of William Duff, 1st Earl Fife, and is buried in the Duff House Mausoleum. He was beloved by all and has a bridge and chapel built in his memory.

Posts

Part 2 of 2

James returned home in September 1813 as the 4th Earl Fife, his father having died in 1811. He was received in Banff and Macduff with huge rejoicing, met by the Magistrates, the principal inhabitants of Banff, the incorporated trades and “all the inhabitants of Macduff”. Flags were displayed at the forts, the shipping, the hills; a salute was fired from the battery and “all the bells of Banff and Macduff rang a merry peal.”. In the evening there were illuminations and immense bonfires in every street, and on Doune Hill there “was one of such extraordinary size and brilliancy as completely illuminated the whole road from the bridge of Banff to Macduff”.

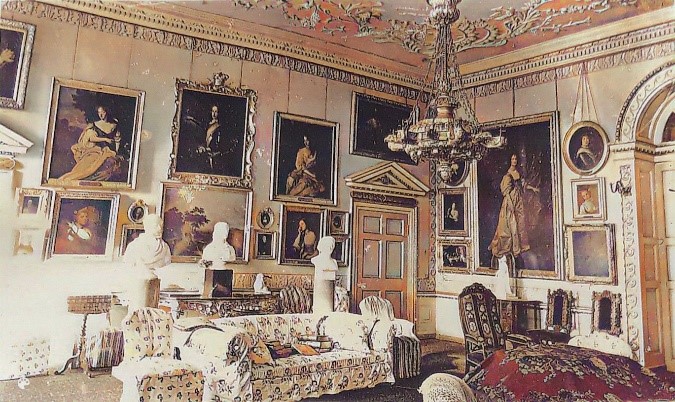

King George IV (as Prince Regent) made him a “Lord of the Bedchamber” (a trusted confidant and advisor), and later – 1827 – conferred on him the “Order of the Thistle” (of which there are only 16 at any time) and the Grand Military Cross of Hanover. James is wearing these insignia in the painting in Duff House’s North Drawing Room. He was also elevated to the British peerage as Baron Fife.

James became the Whig Member of Parliament for Banffshire in 1818, holding it until 1826. He was a keen Mason, becoming the Grand Master Mason for Scotland. In that capacity he laid a foundation stone for Waterloo Bridge in 1815 (opened 1817) and the Regent Arch in Edinburgh (opened 1819) amongst others.

James unfortunately found his resources were substantially curtailed. In 1816 James had to go to court to contest the Will of his uncle, who had left almost everything to his natural son, James Duff of Kinstair. He was ultimately successful, helped by the legal knowledge he displayed, to the delight of his friends and the surprise of his opponents.

During the 1820’s his name was linked to a few actresses, specifically Mademoiselle Noblet, on whom it is alleged he spent a fortune. It was also claimed by some he was the father of Maria Mercandotti, a very pretty dancer and actress he brought over from Spain – but the dates don’t fit with when he first met her mother!

Local good deeds

It is hard to imagine the esteem in which James was held locally, both before and after his almost permanent residence at Duff House from 1833. A very few of the many reasons for him being held in such high regard locally include:

- his support for the local farmers during times of hardship; supplying seed to them and most notably during the potato famine of 1847;

- several improvements and expansions at Macduff harbour; this picture shows men working on the harbour wall in 1842. This added to the prosperity of the town which had been planned by his uncle;

- creating, planning and growing the town of Dufftown (1817), intended to provide accommodation and employment for veterans of the Napoleonic wars;

- paving the pavements of Elgin;

- repaired and renovated much of Pluscarden Abbey;

- building the Fife Arms Hotel on Low St, becoming one of the finest hotels in the north;

- starting a soup kitchen;

- assisting with funds to erect a new church for the Episcopal communion (St Andrews);

- furnishing the County Hall;

- opening the Pleasure Grounds of Duff House to the public for walking and riding;

- developing his lands, planting new trees (including the huge Monkey Puzzle tree in memory of his friend from Spain, the Libertador of Argentine and Chile, Jose de San Martin); this led to the planting one hundred years later in 1950 of the Monkey Puzzle in Banff Castle grounds;

- and his particular delight of seeking out those that needed help. He is said on one occasion to have relieved an aged woman by carrying a sack of meal to her home for her; telling her to sieve the meal well before using it. On her return home she did, and was filled with joy at finding several golden coins.

Apart from his friendship with the King, he had many friends, British and international, and knew most of the key society people of the early nineteenth century. He often had grand parties at Duff House. In 1850, James’s birthday was celebrated (on Mon 7th Oct as the 6th was a Sunday) with flags and decorations throughout the town; arches of flowers were erected at the Fife Arms and Oak Hotel (bottom of Strait Path); even the coaches from Inverness and Aberdeen were decorated with “fantastic and yet beautiful” shapes of flowers. Bells, musicians, guns and mortars entertained a crowd that filled all the space from Bridge St to Greenbanks. There was a huge Ball, held at the Barnyards (now Duff House Royal), another for the youngsters, and a dinner attended by hundreds.

Although enjoying robust health for most of his life, apart from occasional after effects of his wounds from Spain, James took ill in February 1857 and died on 9th March. The Banffie reports that 10,000 people turned out for his funeral. James Imlach, historian of Banff, summed him up as “A warrior and a courtier, a nobleman and a statesman, he rejoiced most of all in the title of the poor man’s friend.”

Part 1 of 2

James Duff – the future 4th Earl Fife – was born in Aberdeen on 6th October 1776 to Alexander, younger brother to James Duff 2nd Earl Fife, and Mary Skene of Skene. The older James, at this stage, realised he probably wouldn’t have a direct heir, and was also somewhat critical of his brother as being “weak”; also his sister-in-law had been described as having “moral laxity and emotional instability” So from the age of 6 our future hero was brought up in Duff House under the care of his uncle, to be groomed as the future Earl Fife. He went to the renowned Dr Chapman’s school at Inchdrewer, and then in 1789 to Westminster School, before going in 1794 to Christchurch, Oxford. However he soon became a student at Lincoln’s Inn and received legal training for three years, which would stand him in good stead in later life.

By 1793 his uncle had described “Jamie” as much “improved”, with “really good principles, and temper, with every prospect of application and good parts”. He had an aptitude for languages, learnt Latin and Greek, and frequently visited the Houses of Lords and Commons. He learnt the style and manner of great public speaking. In 1794 Jamie abandoned his legal studies in London and joined the Allied army on the Continent, fighting against the French Republic. He was present at the Congress of Rastatt, trying to resolve the French occupation of the left bank of the Rhine – until the French resumed fighting in 1799.

Jamie returned to London and on 9th Sept 1799 married Maria Caroline Manners. This was most definitely a love match; the couple enjoyed society living in London and Edinburgh while also spending some time at Duff House. He was appointed to the command of the Banff and Inverness Militia, and he reportedly much improved their discipline.

During a stay in Edinburgh on his militia duties, his wife was scratched on the nose by her pet Newfoundland dog. Not much notice was taken of this incident, perhaps because rabies was only just starting to become known; not even when the dog became bad tempered and bit a groom; the dog was then put down. Within a month however Maria became ill, and although the physicians realised the nature of the malady, it was too late to save her and she died on 20th December 1805 of “undoubted hydrophobia”. She was described as “so well known and so universally esteemed” and was much mourned.

Although James was overwhelmed with grief it was several aspects of his life to date that led to the events that made him a true here. He went back to Europe, joining a combined force of British, Swedish and Prussians, anticipating an inevitable war with Napoleon. Looking for action he shifted to Vienna and joined the Austrian army under Archduke Charles, fighting in battles at Wertignen, Ulm, Munich and others. Even though the French were victorious, James learnt much of military tactics. On hearing of the disturbances in Spain he sailed from Trieste to Cadiz to assist the Spaniards against the French. He learnt Spanish and fought with several of the Junta, but later uniting with an army under Lord Wellesley, later the 1st Duke of Wellington.

He fought at the battle of Talavera in which he was instrumental in moving some guns that then inflicted much damage on the French, and although wounded by a sabre cut to the neck during a counter-attack, still saved the life of a Spanish officer and led a harrying force on the fleeing enemy.

With reinforcements the French soon attacked outposts around Cadiz, and during the battle of Ocana, James was badly wounded while going to the successful aid of a beleaguered fort. The Madrid Gazette said “Lord Macduff and Colonel Roche are the active and indefatigable agents of England with the Spanish armies.” James received much praise and recognition, even if his name was pronounced “Maucdoov” ! He soon recovered and took an active part in many other battles.

Meanwhile, in 1811 his father had died and James had become the 4th Earl Fife, and he prepared to head back to Scotland. Lord Wellesley presented him with a magnificent Damascus sword, ornamented with precious stones on a ground of solid gold, to mark his meritorious services.

The Cortes Generales, the Spanish Parliament, not only made him a General but also a Knight of the Order of St Ferdinand, Spain’s highest gallantry award – their equivalent to our later Victoria Cross. On paintings of him after 1813 he is wearing this medal.

James later life and the good deeds he did around Banff and Shire are in Part 2 of his story to follow.

Agnes was a grand-daughter of King William IV, and married James Duff in 1846 while he was serving there as part of the Diplomatic Service. She was born in 1829, and most unfortunately died in 1869 as a result of falling out of her carriage while in London.

A quote from one of the poems written after her death, demonstrates how well liked she was:

“Beloved by all, like springtide’s flowers,

Her presence did a joy impart;

In and around her princely bowers,

Her presence was a joy of heart.”

James became the fifth Earl Fife in 1857 on the death of his uncle. During his marriage to Agnes they had six children, the last who died in infancy. Their eldest son, Alexander, became the sixth Earl Fife, and on marrying the Princess Royal became the first Duke of Fife.

Agnes and James were quite often at Duff House. Agnes masterminded a major decorative overhaul of Duff House, and today a room is entitled her boudoir, just off the first floor Vestibule. Her body was brought back to Duff House where it lay in state. The Banffshire Journal of the time says “the ceiling and wall of the room were entirely draped in black, the only relief being a wreath of white roses in the centre of the ceiling.” Apparently “as usual”, there were three coffins; the inner being mahogany richly lined in white satin, then a lead coffin, and outside it was encased again in mahogany. During the funeral Agnes was taken to the Mausoleum and lowered into the crypt, the “whole of the top of the coffin was covered in white camelias”. There are a number of art works of Agnes. The newspaper reports that a beautiful bust of her was in it’s usual place in the Vestibule. From an old low resolution photo it seems this sat alongside one of her husband, now in the Aberdeen Art Gallery; both believed to have been done by the renowned sculptor Alexander Brodie.

One of the best known paintings of Agnes was initially believed to have been done by Sir Francis Grant, but is now attributed “after” him, ie in his style. A small photo of it hangs in the Lady Agnes Boudoir today. One interesting aspect of this picture is the dog at her feet, believed to be Barkis. The painting was presented to Agnes by a grateful tenant in 1863, and Barkis was born that year. The dog is commemorated on the gravestone in Wrack Woods.

James and Agnes youngest daughter, also called Agnes, did gain some notoriety in her time. She eloped in 1861 aged just 19, married and had a child, but was soon divorced. Her second marriage, also by elopement, lasted four years. Shunned by much of polite society, the younger Agnes then went to work in a London hospital, and met the eminent surgeon Sir Alfred Cooper. One of his medical interests was venereal diseases, and a scurrilous remark that arose is reported as “Together they knew more about the private parts of the British aristocracy than any other couple in the country”! They had four children, and they and other descendants became quite prominent in society. The best known most recently being David Cameron, Prime Minister 2010 to 2016.

James Duff was born in 1729, the second son of the 1st Earl of Fife. He became the 2nd Earl when his father – William – died in 1763, but it seems he was active in the running of the Duff estate well before that – it is well known that his father was not enamoured with Duff House, even though he had had it built!

30 years after he started developing the Duff House estate, James wrote about some of his agricultural work. He describes the estate with its “many natural beauties from sea views, a fine river, much variety from inequality of ground, and fine rock scenes in different parts of the river; but there was not a tree, and it was generally believed that no wood would thrive so near to the sea coast.”

In other words the area around Banff and Duff House in the first half of the 18th century used to look substantially different. The whole valley had no trees, which must have made Duff House itself really seem to be imposing. Difficult to imagine now, but it shows how the whole lower Deveron valley is a man-made landscape.

James Duff carries on to make it clear that he has proved over a thirty year period from about 1750 that the general belief that trees would not grow so near to the sea coast, was a mistake. In 1787 The Duff park was fourteen miles round, and James claims he has every kind of forest tree, from thirty years old, “in a most thriving state; and few places better wooded”. This was confirmed by some of the well known visitors to the estate.

James writes the above in the “Annals of Agriculture” and over several pages goes on to explain in some detail how to grow trees where the climate is not favourable, and in different types of ground. How experience has taught him what species to mix for success, that the best planting density is 1200 trees per acre. He used to bring trees on, mainly in his own nurseries, for three years and then plant them out, mostly amongst “Scotch Firs” as “nurses”.

In this way James planted 7,000 acres mainly in his Duff and Innes estates – as the magazine editor comments “This is planting on a magnificent scale indeed!”. He says that part of his purpose is to provide wood to the local population – all those Scotch Firs that were cut down once the other trees were established – as coal was so expensive in this region, and made worse by “a heavy and unjust tax on it”!

His article prompt considerable interest and many questions; he writes answers to every question and does not seem to hide any detail.

It is clearly because of James’s foresight that we are lucky enough to have such a pleasant Deveron valley, with it’s wooded river-side walks to enjoy.

Not a rallying cry but a privilege given to Members of Parliament and those that sit in the House of Lords. The title “Earl Fife” was an Irish title and did not entitle the holder to sit in the House of Lords, and hence at various times the Earls Fife were Members of Parliament for Banffshire, or even Elginshire. At other times, the Earls Fife were given a UK title; for example James the 4th Earl was made Baron Fife in 1827 until his death in 1857, and so could sit in the House of Lords.

James the 2nd Earl was a particularly prolific letter writer and the Free Frank became a great cost saving to him. Technically free postage was only for correspondence pertaining to parliamentary or constituency affairs, but it was widely abused. All that was needed was the signature of the sender in the lower left hand corner of the address face; the date and place of origin was also meant to be shown.

That may not seem of particular importance these days, but prior to the postal reforms introduced by Rowland Hill in 1840, the high cost of sending a letter was dependent on both the distance it had to travel, the route it took and the number of sheets of paper; the charge could be paid by either the sender or the recipient. For example, in 1830 it would have cost the equivalent of £4.32 to send a single sheet letter to an address 100 miles distant. Letters were generally folded pieces of paper, as if an envelope was used it counted as an extra sheet and thus cost twice as much! There were many other complications too, whether it went via a capital city or cross country, disparities about how many miles between places, and at that time even what a mile was (England was 1,760 yards; but a Scots mile was 1,976 yards, and although that was phased out early in the eighteenth century, the Irish mile of 2,240 yards applied until 1839, hence would have included the second example below!).

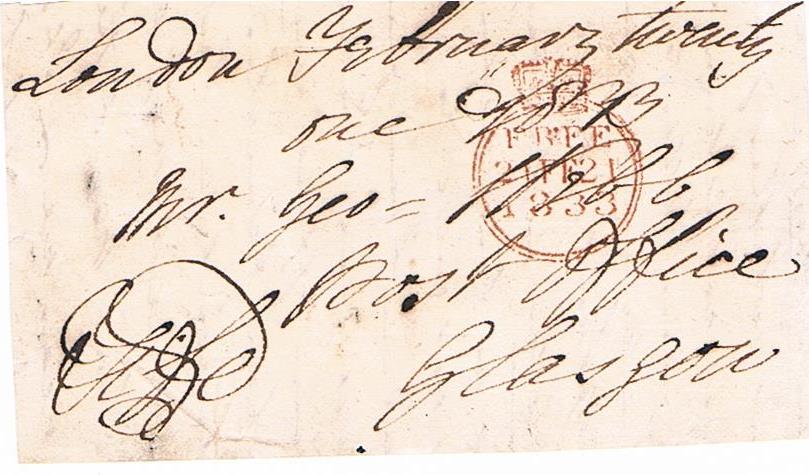

James the 4th Earl similarly had the same Free Frank privilege. This example was sent from London on 21 February 1833 and is addressed to Mr Geo. Gibb, Bank Office, Glasgow.

Address from letter sent by 4th Earl Fife in February 1833 to Glasgow

Such mail could be keenly collected when disposed of, trying to once again abuse the Free Frank system. Hence the trend was often to retain only the address part of the letter and to discard the rest, so the content of this particular letter is unknown.

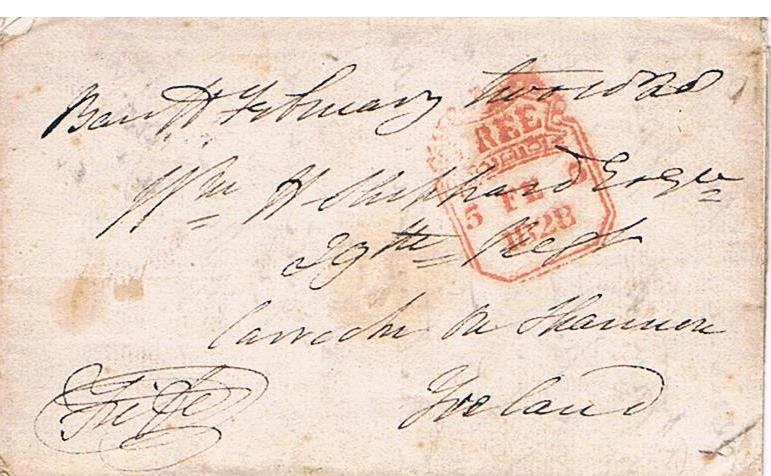

This second example, fortunately complete although difficult to read, is also signed by the 4th Earl Fife but this time when he was in residence in Duff House, Banff. It is dated 1st February 1828 and addressed to a Mr W Sheppard Esq, 29 Regiment, at an address in Ireland. What is particularly interesting about the letter content, is that it wasn’t written by the Earl, but is a short message to the addressee from his father, A. Sheppard.

Address from letter sent from Banff in Feb 1828 to Ireland

The Free Frank system continued until the postal reforms introduced in 1840 – when stamps much as we know them today were introduced; just 1d per half ounce to anywhere in the country. The parliamentary privilege was then changed to a set value of pre-printed postage; today that stands at £7,000 per year, although looking at the list, very few MP’s use that much. An MSP can currently claim up to £5,500.

19th August 1824.

General José Francisco de San Martin y Matorras was a name to be conjured with in Banff early in the nineteenth century. This general became a great friend of James, the 4th Earl Fife, after they met during the Peninsular Wars in Spain. At that time they had both given allegiance to Spain, but José was born in Argentina, and in 1812 was drawn back to South America. Interestingly the Burgess Roll of Banff for 1824 lists José as from Colombia, rather than Argentina; this may in fact have been correct as José’s last South American domicile was in Guayaquil, originally in Peru, at that time very recently annexed to Colombia and today in Ecuador.

It was actually James Earl Fife – who had returned to UK in 1811 as his father was ill – that organised José’s trip from Spain via London, as switching allegiances to now fight against Spain from being one of their most successful military leaders was a delicate situation!

As a great strategist José was the General that led Argentina (then known as the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata) to gain independence from Spain, and also led armies to liberate Chile and then Peru. He ceded to the better known Libertador Simon Bolivar in 1822, left his life in the military and politics and came back to Europe.

For 17 days in 1824 he visited his friend James at Duff House – the really will liked and respected fourth Earl Fife. During that stay, specifically on 19th August, the town of Banff granted him the freedom of the Burgh. He probably cut quite a dashing figure at the time; the artist for the painting shown here is not known, but it was painted 1825 or 1827 so quite representative of his visit to Banff.

José went to live in France, and died on 17th August in 1850. One hundred years later and the then Argentine ambassador, Carlos Hogan, paid a celebratory visit to Banff on 25th October. Part of his visit was planting a native Argentinian “Monkey Puzzle” tree in Banff Castle grounds – where one can be seen today together with it’s plaque. There is a story that the first winter was not good for the actual tree planted by Carlos Hogan and another was quietly substituted!

Just over two years later and Banff is given another accolade in memory of José de San Martin. Carlos Hogan went on to become the Argentine Minister of Agriculture, and arranged for a square in Buenos Aires to be called “Ciudad de Banff” – Town of Banff – “in recognition of the hospitality given to the Argentine Liberator Don José de San Martin by Banff in 1824, and the freedom of the Burgh they conferred upon him.” That Plaza retains that name to date in Buenos Aires.