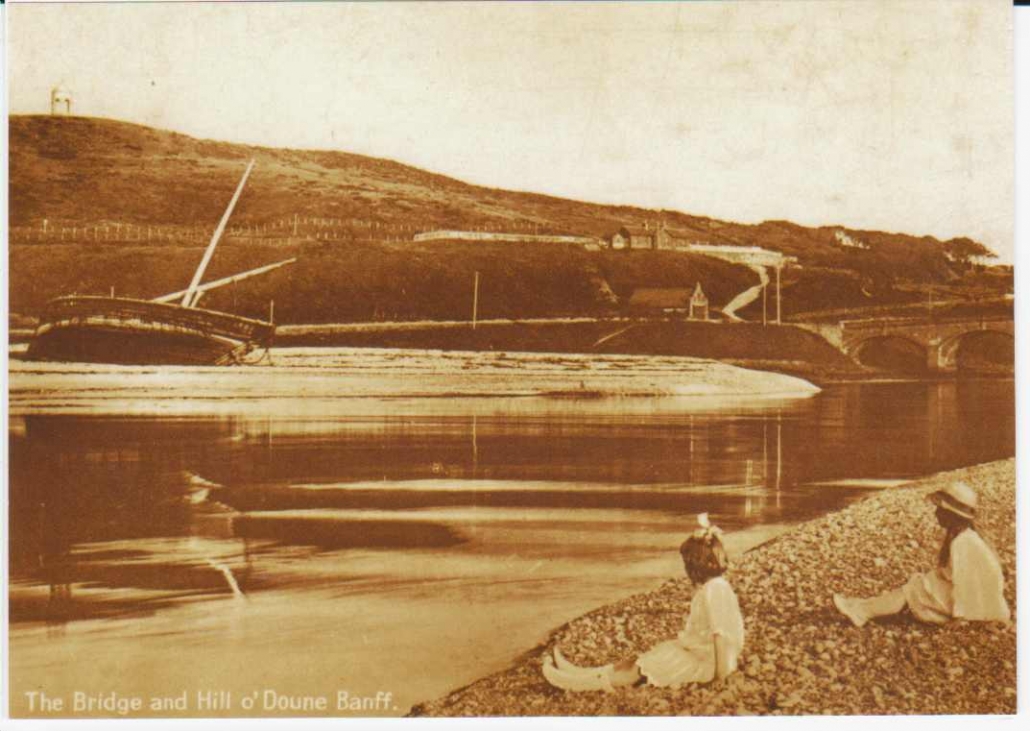

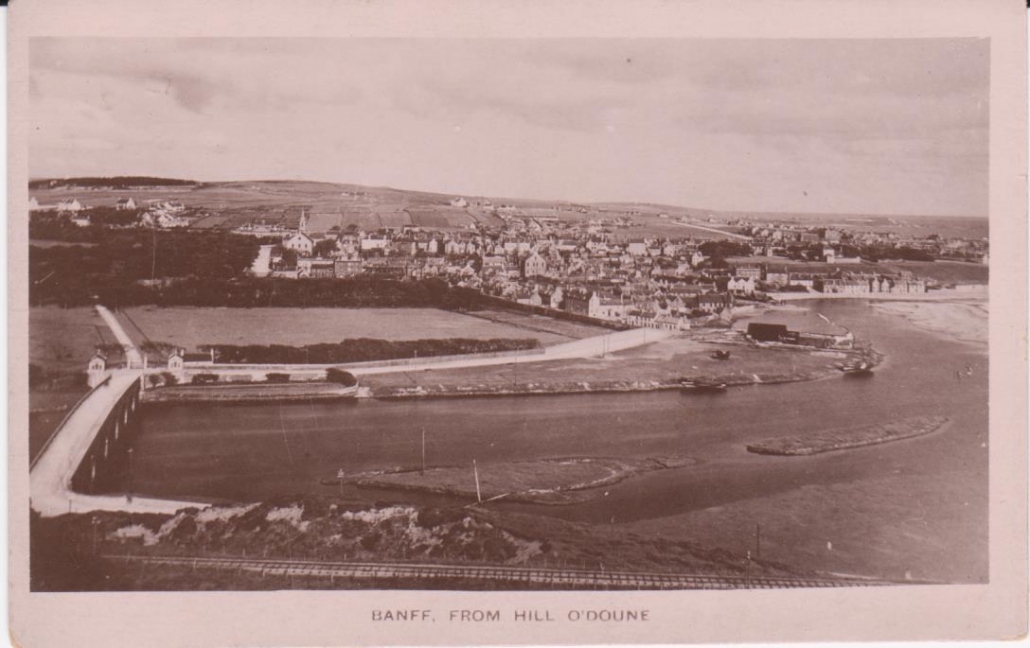

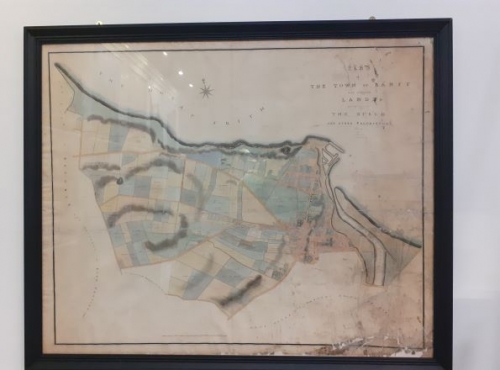

In the Museum of Banff there is a new exhibit, a map of Banff in 1826. This is a coloured map with great details of the town shown, including who owned parts of the town, at the time. Large areas of Banff were owned by the Earl of Seafield but areas were owned by organisations such as the “Gardeners Society” and “St John’s Lodge” At this time Banff is almost two separate towns – the Sea town, the area from St. Catherine Street North and the rest of the town, covering Low Street, High Street and the surrounding area. It stops short of Duff House and its grounds. This can be compared in the museum with a 1756 plan of the town and an 1823 map, by John Wood. These maps were produced by independent map makers or land surveyors, before the days of the Ordnance Survey.

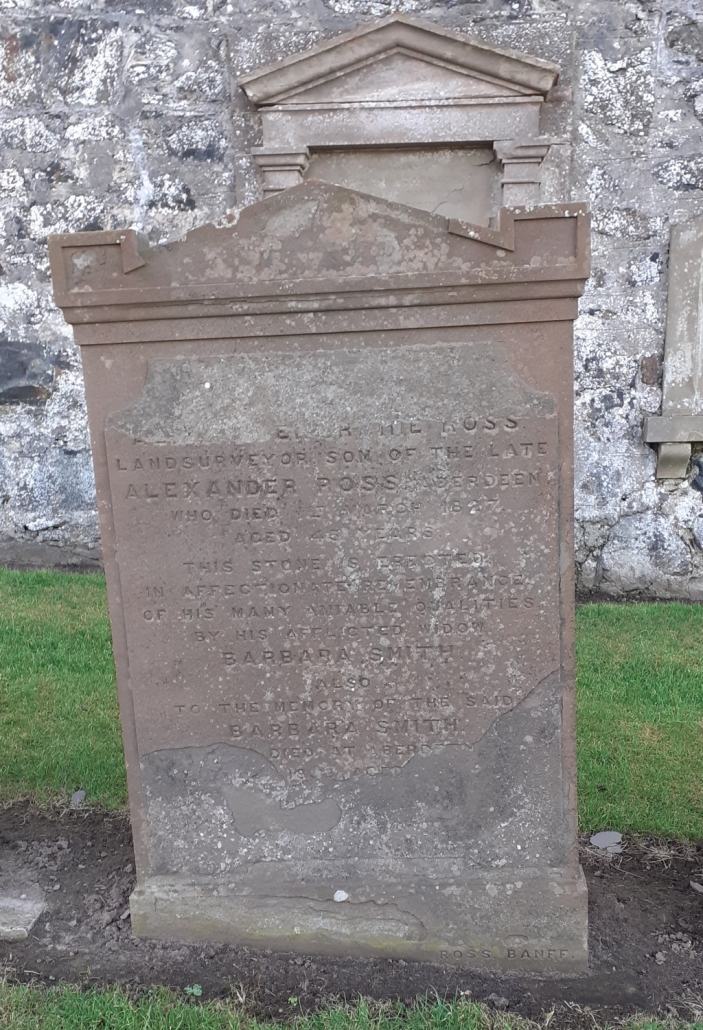

The 1826 map was created by Alexander Irvine Ross, a land surveyor from Mains of Tyrie. He was involved in the production of a series of maps created by James Robertson (1783 – 1879) of the shires of Aberdeenshire, Banff and Kincardine in 1822. James Robertson was referred to as “the Shetlander who mapped Jamaica and Aberdeenshire”. Alexander Irvine Ross also produced a four sheet map covering Aberdeenshire and Banff in 1826, mentioned in the New Statistical Account, written by the Reverend Francis William Grant in 1845. This possibly refers to the maps which were published in John Thomson’s Atlas of Scotland, 1832.

The map came in to the possession of the late Bob Carter who donated it to Banff Preservation and Heritage Society. It was in poor condition and in need of conservation work. The map was cleaned and relined by the High Life Highland Conservation Service, with a grant from the Area Initiatives Fund. This meant that a unique and valuable part of Banff’s history has been preserved for future generations. The map is best viewed in person at the museum but if that’s not possible it can be seen on our website – https://www.bphsmob.org.uk/collection/various_items/1724_1826_Map.html

Banff Preservation and Heritage Society and Museum of Banff

Banff Preservation and Heritage Society and Museum of Banff