A Banff Foundry crest on a gatepost in Banff

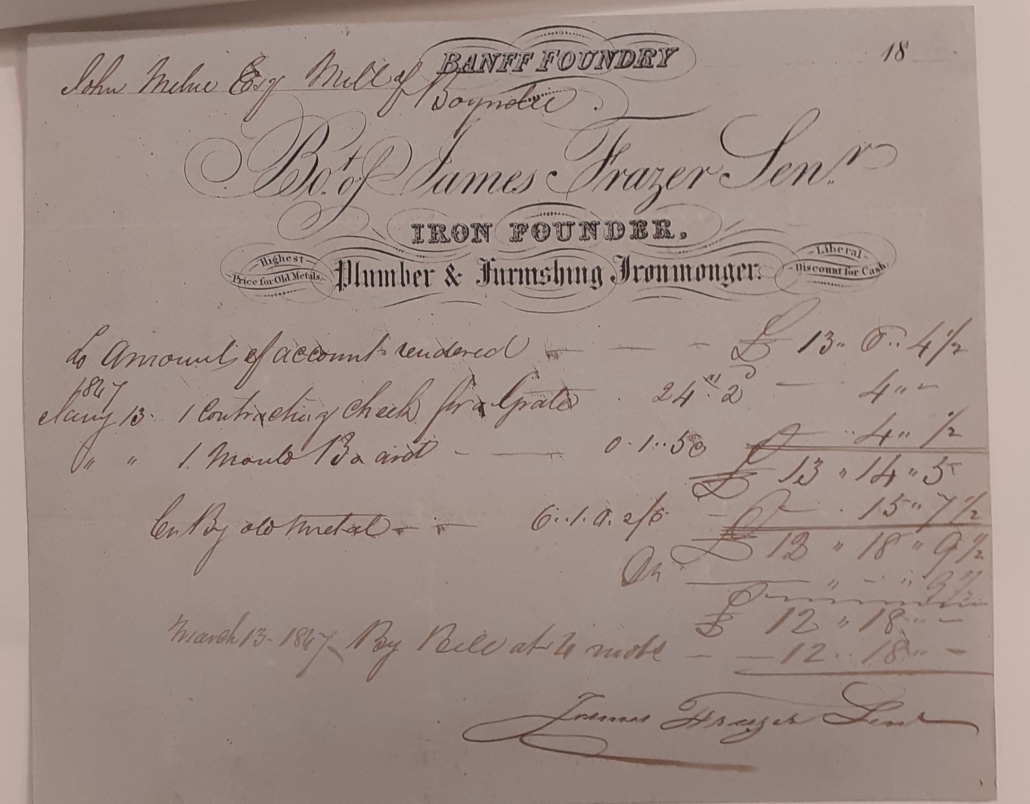

An Invoice from James Fraser, Banff Foundry, 1800s

Chapel on the corner of Carmelite Street and Reid Street, with the Foundry area behind it.

If you look carefully as you walk around Banff you can still find traces of a major industry in the town (see the photos).

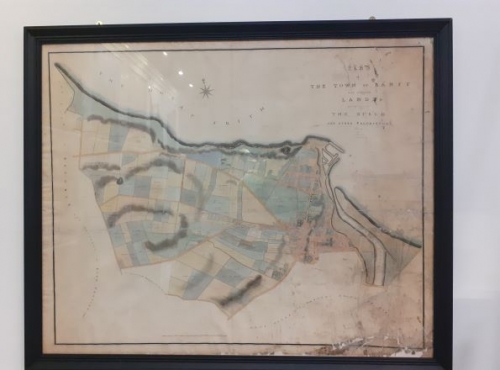

The area where Tesco supermarket is now would have been very different before 1955. Banff Foundry was developed on the site of a blacksmith’s forge (Robert Thomson’s blacksmith shop), bounded by Reid Street, Carmelite Street and Bridge Street. The industrial forge was installed in 1827 by William Fraser.

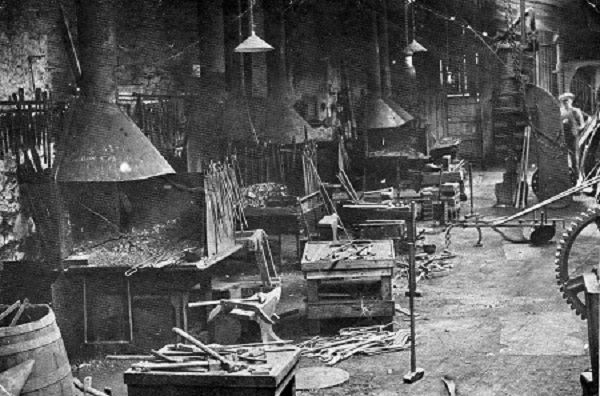

In 1858, an article in the Banffshire Journal and Advertiser gave details about the new Foundry and the iron-making process.

“The large new casting room is 60 feet long by 30 feet wide”. “The furnace is like a huge lemonade bottle, from which a chimney to a considerable height rises. On the side, and near the head of the furnace, at a spot exactly corresponding with that on which the aerated water vendor pastes his label, is a large circular opening, opposite which a platform is extended. From this platform the workmen (who must partake, somewhat of the salamandrine character from the amount of heat they endure) feed the furnace, by the opening, with metal and fuel.” (Banffshire Journal and General Advertiser, Tuesday 23 November 1858)

The Foundry made a wide range of agricultural implements, gates, fences etc. Many people collect old agricultural implements made in Banff by G. W. Murray and later Watson Brothers, which can still be seen today. (See the accompanying photos.) Around Banff, there used to be drain covers with Banff Foundry written across them.

In 1867 to 1869, the Foundry is described in the Ordnance Survey name book as “A large iron foundry on Reid Street, occupied by G W. Murray, the property of the Aberdeen Town & County Bank.”

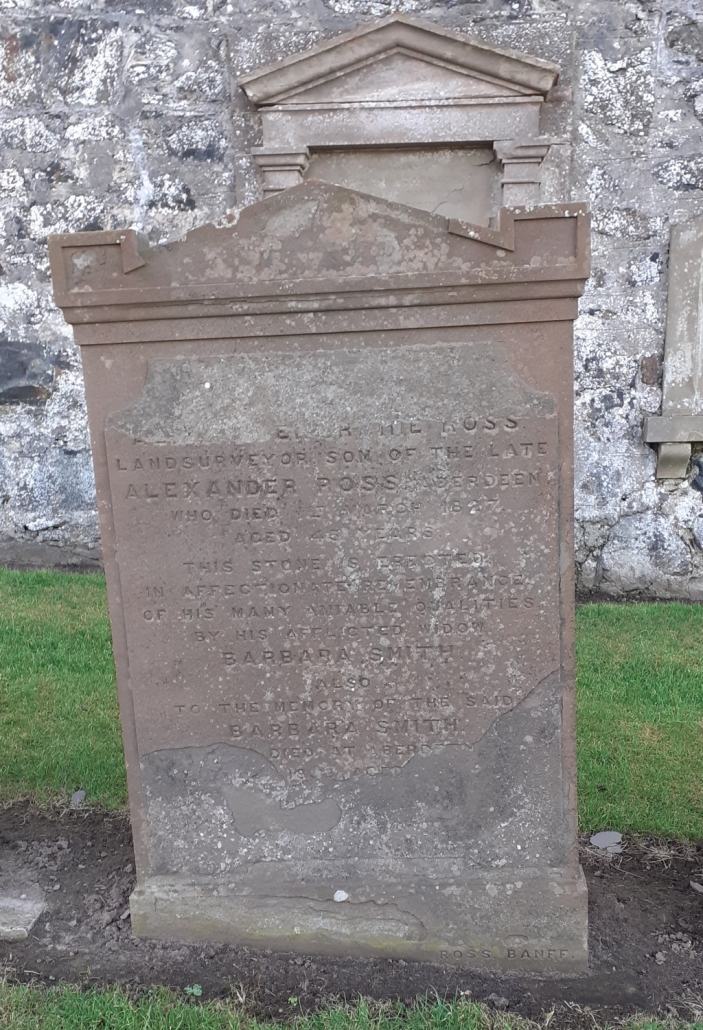

G.W. Murray was the owner of the Foundry from 1863 until his death in 1887, aged 53 years. He had an adventurous life, living in Australia from 1852 until 1862, where he made his fortune. (Australia’s gold rush started in 1851). George Wilson Murray married Cecilia Blake in 1862 and built the Italianate house at South Colleonard, just outside Banff.

The Foundry had a tumultuous history, burnt down in 1892. However, it recovered very quickly and the business thrived, employing 35 people in the 1890s.

In 1902, the Foundry, then being run by the Watson brothers, exported agricultural machinery worldwide, e.g. Cape Colony, South Africa; Montevideo and Hobart, Tasmania, being just a few of the destinations.

BPHS

BPHS

Banff Preservation and Heritage Society and Museum of Banff

Banff Preservation and Heritage Society and Museum of Banff

A. Lyon

A. Lyon