This picture is of the war memorial at Duff House. Poppies in remembrance of the British that died, and the Forget-me-nots as the German flower of remembrance. This is one of the very few joint nationality war memorials in existence. It is placed on the spot where one of the bombs fell as part of the events recounted below.

“In the morning at nine o’clock the klaxon for roll call went. We were all lined up outside. We heard an aircraft and he came pretty low. He must have been coming out from Norway or somewhere [like that]. I think it was a reconnaissance aircraft. They are loaded with bombs too. I think he was on a reconnaissance mission to explore northern Scotland, and he saw this camp down there. He saw the tents of the guards up on the hill, and he saw this building there with people outside and thought, ‘let’s give them a lesson,’ so to speak. Before we witnessed that it was over, the bombs fell. Miraculously, I wasn’t hit by anything, but I lost six of my crewmates from U-26 during the air attack mistakenly made by Hermann Göring’s ‘Flying Circus’. Two bombs went into the elevator shaft as duds, they never blew up. But two guards outside, they were killed through the bombs.”

These are the words of Paul Mengelberg, one of the true eye-witnesses as the bombs fell. This took place on 22nd July 1940 – 81 years ago this last week.

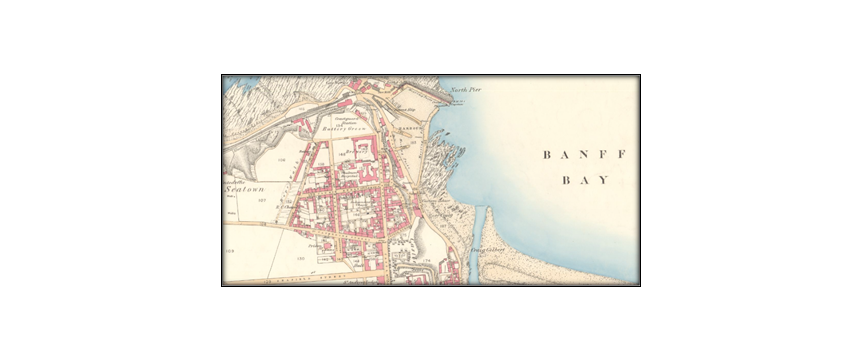

Paul Mengelberg continued, “Those that died were given a soldier’s funeral by the British forces at the gravesite in Banff.” Later writers mention that the bodies were eventually repatriated to Germany, but this is not correct. In 1959, an agreement was concluded by the governments of the United Kingdom and the Federal Republic of Germany concerning the future care of the graves of German nationals who lost their lives in the United Kingdom during the two World Wars and so a new German Military cemetery was established at Cannock Chase, Staffordshire, which is where the six men are now buried.

The two British soldiers who were killed were of course returned to their families, one in Newcastle, one in Blair Atholl.