Were humans in Banff and Macduff 3,000 years ago, or even earlier? It seems they must have been and even back then had an appreciation for the beauty of our countryside.

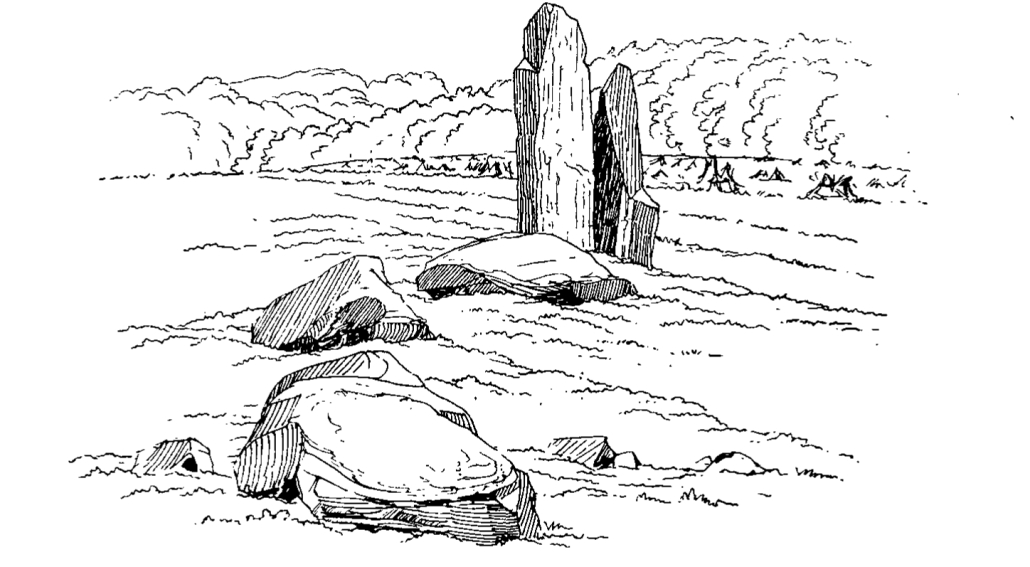

One of the pieces of evidence, about a mile south of today’s Banff Bridge, as a small island in the middle of a large field, there are a few stones, lying at all angles. Today, none can be said to be truly upright.

The first found written record of these doesn’t appear until 1780, described by Thomas Pennant as “several large stone pillars, tending to form a semi-circle, and are doubtless the remains of a Druid temple.” Unfortunately there was no accompanying drawing! The idea of a “Druid” temple, often associated with sacrifices “in honour of immortal gods” was a theory applied to stone circles through to the mid-nineteenth century.

An in-depth survey was conducted in 1903 by Mr Fred Coles and reported in the 1906 Proceedings of the Society of the Antiquaries of Scotland. By this time only two stones were left standing, and an inspection suggested only one of these was in it’s original position – which seems to be the stone most upright today.

Mr Coles concludes that this used to be a recumbent stone circle, ie one stone lying horizontally, with an upright at each end of it – as many such circles can be found in the northeast of Scotland. Unfortunately the Gaveny Brae circle has had stones removed and has been much damaged from “a deplorable want of respect” over the centuries in agricultural districts, a sad fact which Mr Coles much laments.

The position of the site is on a level part of a ridge looking north along the Deveron valley to the Moray Firth – from visiting the site it would seem likely the position was specifically chosen. In 1901 the artist Robert Allan painted the view from seemingly the position of the stone circle, which is very comparable to a more modern view (this one with one stone in shot):

The pillar of smoke or steam just to the right of centre in the Robert Allan painting being a train at Banff Bridge station!

The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland published their detailed review of all the stone circles in north east Scotland in 2011 in their book “Great Crowns of Stone”. By this time the Gaveny Brae stone “circle” is so unlike a circle it is relegated to an eight word reference in “Other Monuments”!

As to the real uses of these “Stonehenges of the north”, perhaps we shall never know. It seems that their use changed over time after being places of worship and sometimes burial sites in the Bronze Age, but less respected as times changed. There is much discussion in the papers of the Banffshire Field Club (available on line) on this subject.

If you are looking to visit the site, on the latest Explorer and Landranger Ordnance Survey maps the Gaveny Brae stone circle is marked as just “Standing Stone”, south of the Distillery; on the previous “1 inch” maps it was labelled “Cairn Circle”, although the obvious mound is believed to be just the result of farming, and not a burial cairn.

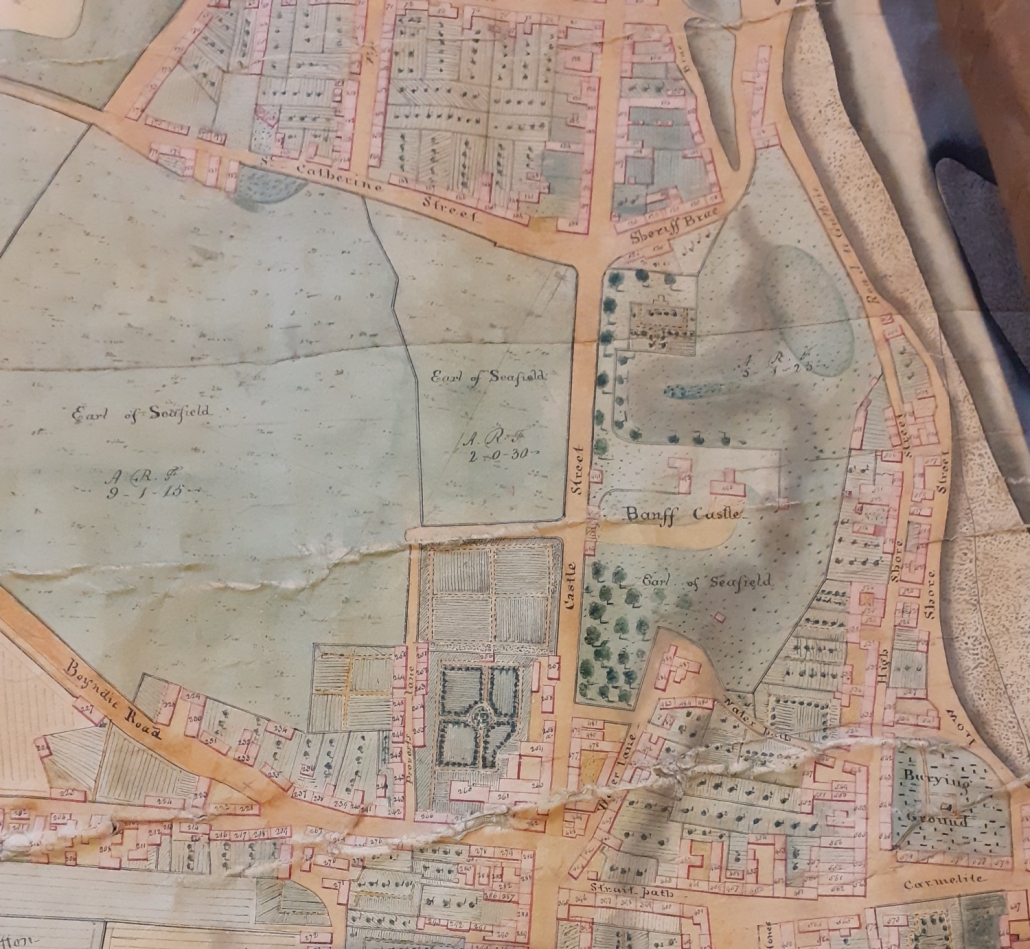

On the plus side, at least the Gaveny Brae site is known and marked and visible; another reported stone circle at the top of what is today Strait Path in Banff, the last stone of which was reported as the “Grey Stone”, is supposedly buried beneath the pavement!

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB