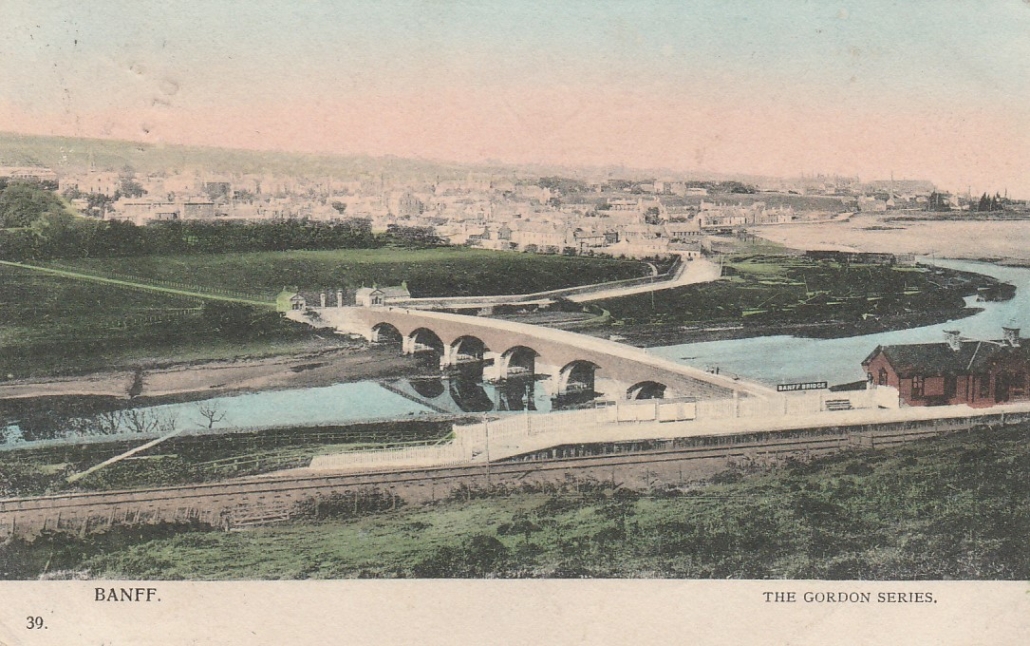

Today the River Deveron heads in a fairly straight line into Banff Bay, but it used to divert west and run along the sea wall of what is today Deveronside, in 1906 nearly destroying some properties.

Posts

Since the early 1800’s the Duff family have had a connection with Argentina, and specifically since 1824 so has the town of Banff, through giving the Freedom of the Town to José de San Martin, a friend of the 4th Earl Fife. While José visited James in Banff, James never travelled to Argentina. As far as can be found the first Duff to visit Argentina was James’ brother, Alexander Duff in 1807. Alexander was brought up in Banff, and currently rests, with his wife, in the Duff House Mausoleum.

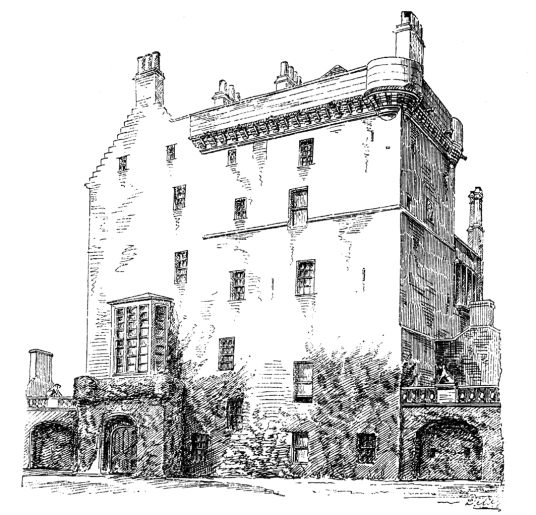

Alexander, born 1777, was the second son of the 3rd Earl Fife, and as was quite common, as a second son his career was probably always destined for the army. The 2nd Earl brought both brothers – his nephews – to Banff for their initial education (see also “Duff House’s Own Local Hero”), firstly at Duff House, but then with Dr Chapman at Inchdrewer.

In May 1793 Alexander joined the Army as an Ensign at the age of sixteen, joining the 65th Berkshire Regiment at Gibraltar. In 1794 he was promoted to Lieutenant and the next year to Captain in the 88th Regiment (the Connaught Rangers). With the 88th he served in Flanders and in 1798 was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel at just 21 years old. He served in the East Indies and Egypt, taking part in the capture of Alexandria. In 1806 he was part of the force that took control of Montevideo as part of the British aim to gain a part of the riches in South America, by wresting some areas from the Spanish. In 1807 he was commanding one of three columns which landed in Buenos Aires, but due to the poor tactics of General Whitelocke, later court-martialled due to his incompetence, he surrendered before reaching his objective of reaching the Great Square. No censure was placed on Alexander, and he was promoted full Colonel, then Major General in 1811.

He was clearly a capable and well-liked officer as reported in several accounts. In 1821 he was promoted to Lieutenant-General, and full General in 1839. He was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Hanover in 1833 – the same as his older brother James 4th Earl Fife had received in 1827. King William IV knighted Alexander in 1834.

General Sir Alexander became the local Member of Parliament from 1826 to 1831 continuing the family practice, although his first attempt in 1820 failed by one vote, and nearly resulted in civil insurrection between the Duff and Grant supporters in the town of Elgin – fortunately defused by Lady Anne Seafield (on the Grant side) by sending her 700 clansmen back to the Highlands.

Alexander’s home was Delgaty Castle, part of the family estate at the time. In 1812 he married Anne Stein, and had five children. The oldest died at just a few months old, but James, born 1814, became 5th Earl Fife when Alexander’s brother, James 4th Earl, passed in 1859. Their fifth child, born 1824, they named Louisa Tollemache – an unusual Christian name; whether this was in memory of her uncle’s late wife’s family, the Tollemache’s of Helmingham in Suffolk, has not been confirmed (James 4th Earl had married Mary Manners, the daughter of Lady Louisa Tollemache and John Manners, who died in 1805 – see “Duff House’s Own Local Hero”).

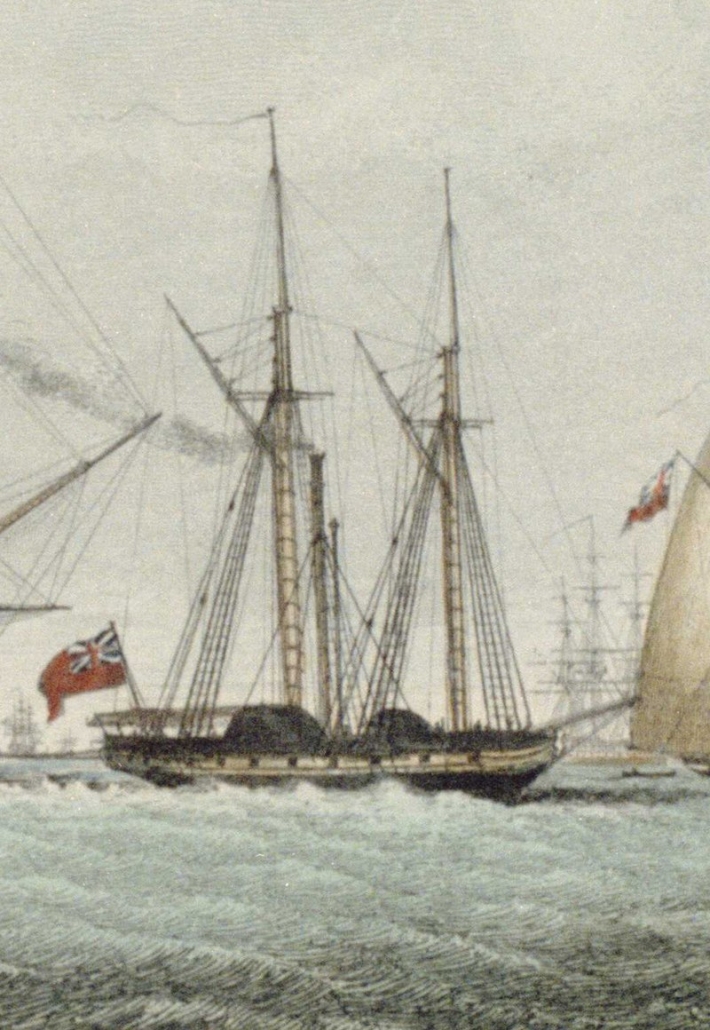

In 1851 Alexander passed away in London, but his body was transported to Banff on HMS Lightning to be interred in the Duff House Mausoleum; Anne, his wife, was also interred there 8 years later.

For interest, the HMS Lightning was one of the first steam warships in the Royal Navy, 126 foot long, driven by side paddles, launched in 1823 and in service until the late 1860’s. She must have been quite a sight coming into Banff Bay. There is a detailed model of her is in the Royal Museums Greenwich.

A rare photo came to light recently showing some members of a Brass Band, partly in uniform, in the grounds of Duff House. With the kind assistance of Gavin Holman who has extensively researched early Brass Bands throughout the UK, as well as our own research, we have been able to ascertain that in the last half of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth, four different Banff Brass Bands have been recorded. The first was around 1857/1860 when there was also the Banff Rifle Volunteers Brass Band. Mr Sutherland then organised a Brass Band in 1893, but it seems that was different from the one conducted by Mr R W Hutcheson around 1899. This latter is recorded as parading around the streets of Banff on Hogmanay for the turn of the century – although they did stop for midnight!

But this photo clearly shows the band members in and around a motor car; now identified as a Renault Limousin (there were several models) which were only built from 1912 onwards.

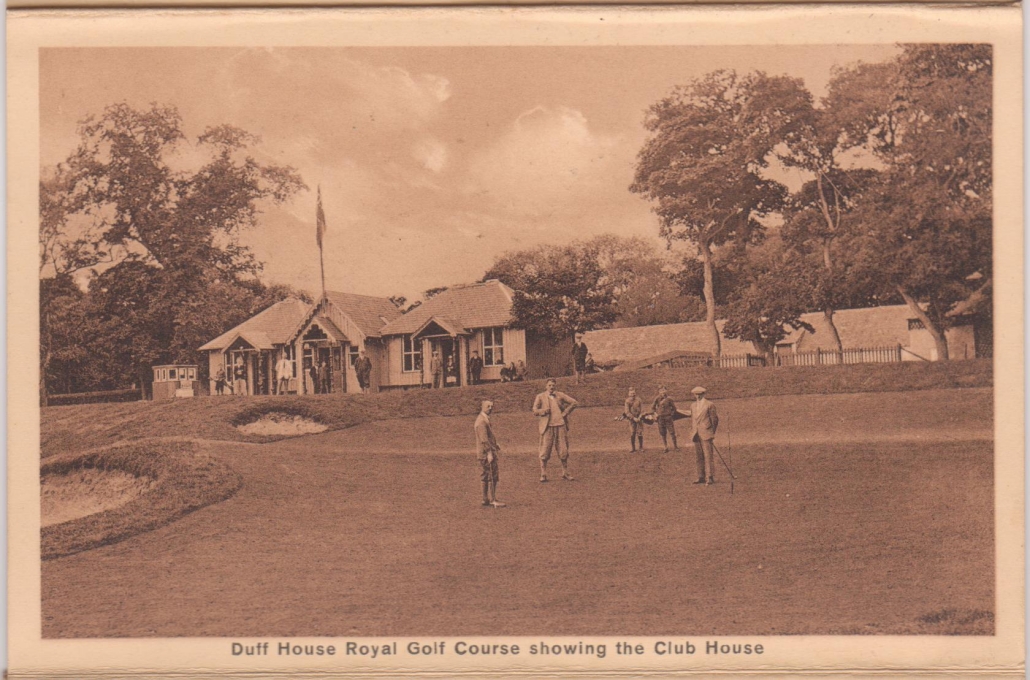

A new Banff Brass Band was formed by Mr Arthur Wilson in the summer of 1913 and it is supposed that this photo must be this band. One of their first engagements it seems was at the Macduff Swimming Gala on Wed 20th July, held of course in the harbour (20 years before Tarlair was built). No doubt they also attended many other local events. They also organised their own dances including at St Andrews Hall. But on Wed 30th July they played at the opening of the new Tea Rooms at Duff House Golf Course on Wed 30th July 1913 (by this time Duff House itself was a Sanatorium); in view of the location of the photo perhaps this is the date of the photo.

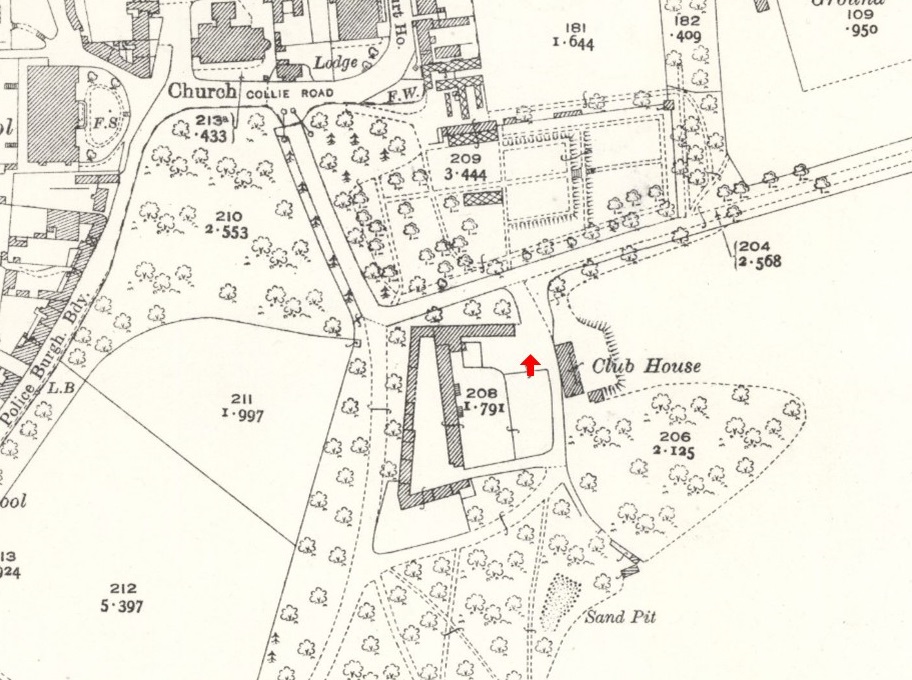

The location is shown on this map by the red arrow.

The Vinery can be seen in the photo and on the map, and it is of course more than fifty years before the present “New Road” was built from Banff Bridge to the town. The present road is raised on an embankment, but the original Duff House drive was not, as show in the photo below. The main photo of this Story was taken just to the centre left of this image, looking left to right across the driveway.

The view in the main picture above therefore, looking north, is through gaps in the hedge, to the original Airlie Gardens (as they are known today) as laid out in the 1860’s by Lady Agnes, wife of the fifth Earl Fife, through to the Vinery. The map shows the part of the old Barnyards – the old Duff House stables – that can be seen to the left in the photo. The first Golf Club Pavilion – Tea Rooms? – is out of sight to the right of the main photo. The main photo of this Story was taken towards the centre right of this photo of the Pavilion.

Note: For eagle-eyed readers please note the 1928 OS map as shown above depicts the new Golf Club Pavilion opened in 1926, not the original as in the photo above. It also shows an extra greenhouse in Airlie Gardens built circa 1925, not there in the main photo where the view is right through to the Vinery.

If any reader has any further information, or insights, into this Brass Band or photo, we would welcome them being in touch.

At the present time, in the Grand Salon in Duff House, is a magnificent Christmas Tree, helping to create a festive and relaxed atmosphere within Duff House. Many thanks to the Friends of Duff House.

However it seems it may be only a pale reflection of the tree that stood in the same room 155 years ago, in 1868. This was at the behest of James the 5th Earl Fife and his Countess, Agnes. Not only that, they held a party with numerous guests, in the manner of what was becoming a tradition in Victorian times; those invited were not just the Duff family but all the servants from the House and the estate, including all their wives and families.

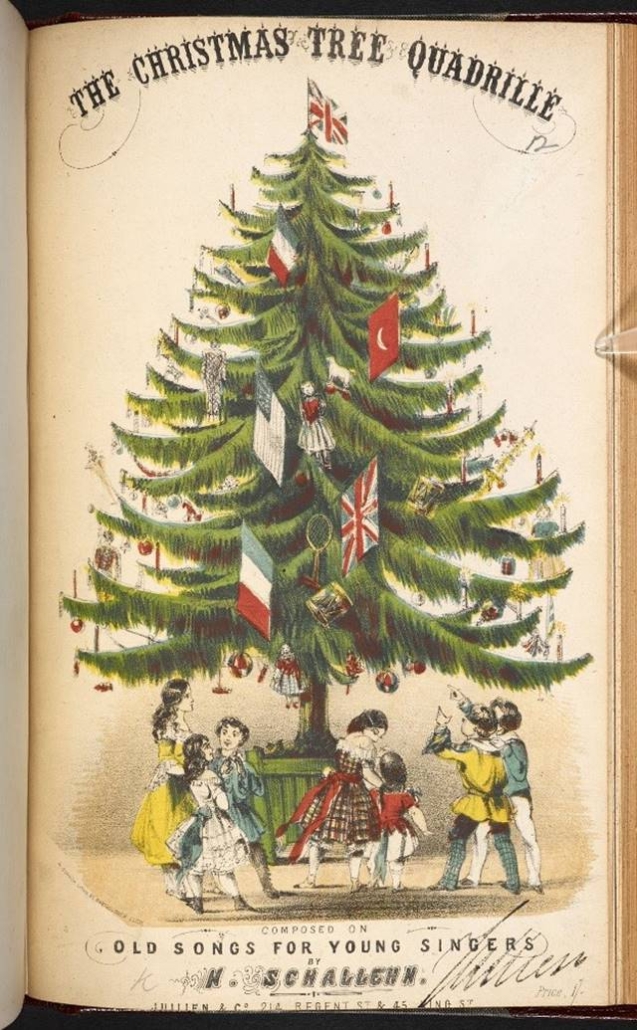

The magnificent and beautiful tree was “prettily decorated with flags and loaded with a multitude of presents”. Having a Christmas Tree was a practice introduced by Prince Albert in circa 1840, bringing the tradition of several decades from his native Germany. The drawing above of the Royal Family’s Christmas Tree was published in 1848 in the Illustrated London News – the first known picture of a Christmas Tree in the UK. The idea quickly caught on around the country.

The inclusion of flags as part of tree decorations was not just a Duff House practice at the time, but is illustrated on this cover below from the 1860s. The Duff family was clearly right on trend!

Music for the occasion was provided by Lady Alexina Duff, aged 17 at the time, on a harmonium; and some solos were sung by one of the servants.

But what made the occasion so special it seems, was the effort taken by Lady Agnes and three of her daughters, Anne, Alexina and Agnes (it seemed they liked names beginning with “A”, also having an Alice and Alexander – later the 6th Earl Fife and first Duke of Fife!) to choose presents for each of the individuals at the party, all piled high under the tree. Each present was wrapped – a practice introduced from America in the 1850s, and each had a name on it – one for every guest. The servants got dresses or articles of clothing, children had toys or books all chosen specifically for the person; “not a few of the presents were valuable and costly” said the Banffshire Journal.

Then there was a sumptuous supper served (not sure by who!) and at midnight Lord Fife gave a speech. The news he gave was that he, his wife and son, Lord Macduff, loved living at Duff House and would spend as much time there as they could – which was greeted by cheers and applause. He also gave the news that an extension would be built on the west side of Duff House, with the work starting in February 1870 – the wing that we now know was bombed in 1940 and no longer exists above ground (except for the war memorial).

In the Duff House Mausoleum, just inside the door, is a list of who in 1912 was believed to be buried in the crypt. This includes four people who do not have the surname of Duff – instead “Tayler” (the “e” is not a mis-type!).

This name Tayler was introduced to the Duff family when the elder daughter, Jean or Jane Duff, of the 3rd Earl Fife married William Alexander Francis Tayler in 1802. As close relatives – Jane’s older brother James became the 4th Earl Fife – they were given Rothiemay House to live in. This building had a fire in 1964 and was demolished, although the gatehouse and some other buildings remain. This is a 20th century photo of Rothiemay House; the feature picture is at is was in the mid nineteenth century – much as Lady Jane Tayler would have known it.

During her life Jane was held in much esteem by the locals around Rothiemay but also in Banff where they were frequent visitors. As evidence of how much she was liked her obituary recalls that “her kindness was not occasional, or by fits and starts, but perennial”. The Banffie wrote “she has gone – and will be missed by many, but the good she has done will live after her, and there will be many hereafter to speak – and the witness is on high – of the good deeds and alms which she did”.

The four Taylers at rest in the Duff House Mausoleum are:

The Honourable, the Lady Jane Tayler, died 22 May 1850

Alexander Francis Tayler, died Sep 1854 (husband)

Alexander Tayler, died 26 Jul 1809, age 6 (son)

Alexander Francis Tayler, died 8 Nov 1828, age 14 (son)

Jane and Alexander had six other children as well as the two above, although it seems they were beset with problems.

- The first born, Alexander, died in an accident at Duff House on the day of the birth of his brother, William. Alexander was pushing amongst adults trying to see his new brother and a unfortunately knocked him and he feel into a bath of boiling water. He survived a few days but his injuries were too severe;

- Anne, the second born, also died in an accident but it’s nature is not known;

- William, born 1809 at Duff House, later in life married his cousin Georgina, granddaughter of Captain George Duff (see the Story on this website entitled “Trafalgar”). Two of their children became celebrated as historians of the Jacobites and the Duff family itself (Henrietta and Alistair), and the oldest as an accomplished artist;

- Jane Marion born 1810 died 1869;

- James George born 1811 died 1875;

- Alexander Frances (in the Mausoleum) born 1814, died 1828 of measles;

- George Skene, born 1816 became a Commander in the Royal Navy, died 1894;

- Hay Utterson, born 1819, died 1903.

The two children in the Mausoleum were born deaf and dumb, as was Hay the youngest. This seems to have been a sad inheritance from their great grandmother, Mary Forbes, but does not seem to have re-occurred.

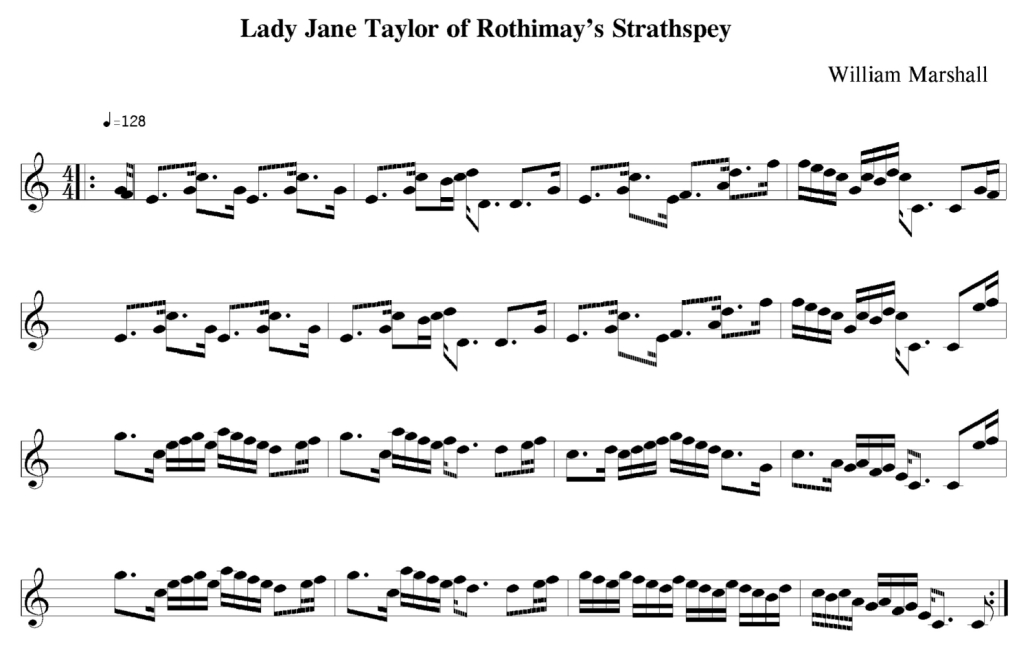

Alexander and Lady Jane were very well connected around the area, not only with the local population around Rothiemay, but elsewhere because of their family connections. There are many newspaper reports of them attending events in Banff in the first half of the nineteenth century. They were very much part of the gentry and mixed accordingly. One little piece of evidence of this is that William Marshall, one of the greatest composers of Scottish fiddle music, named one of his 257 tunes after her; no doubt heard in Rothiemay and Banff:

This Story was written while looking out the window at a wet and windy day. Almost 149 years ago to the day, there was an even worse storm, described nationally as a hurricane.

A Banff eyewitness described it as “Most awful rough day, a real hurricane and raining too”.

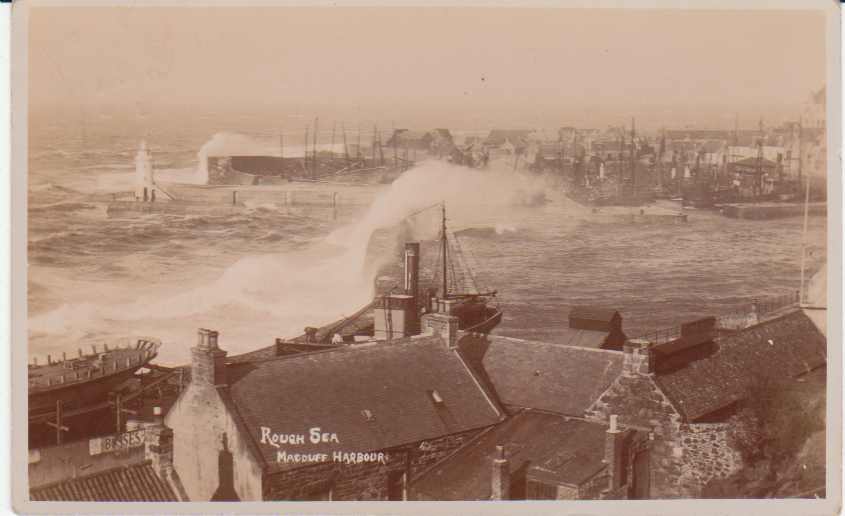

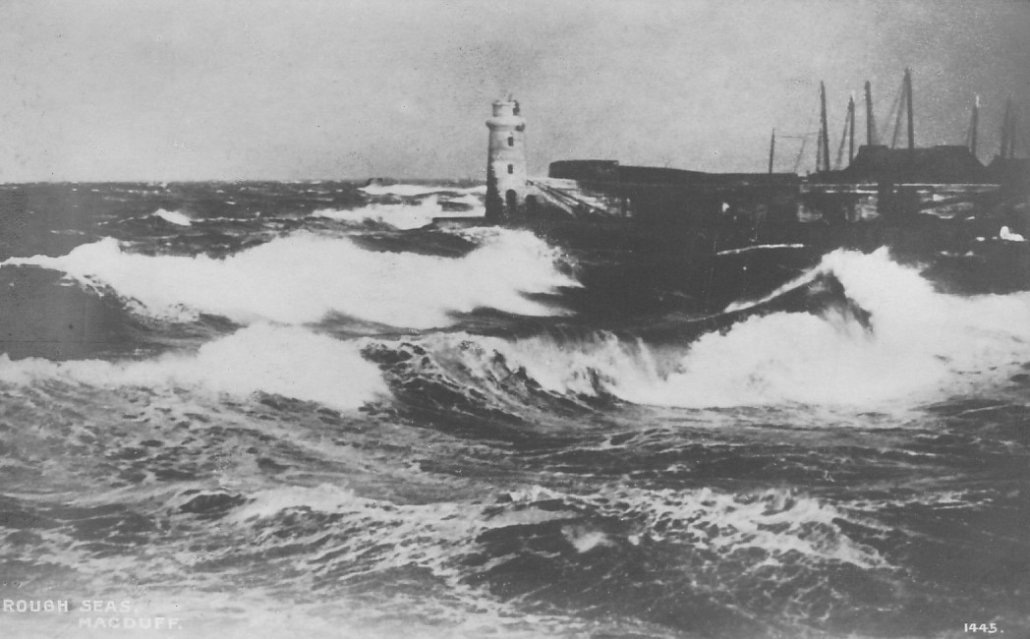

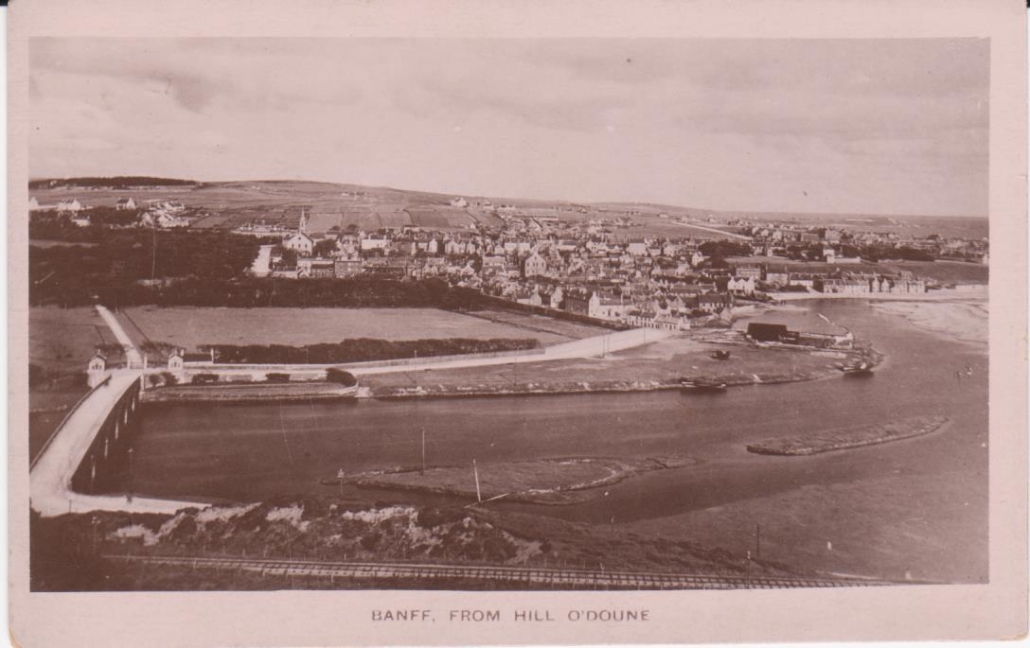

This photo was taken after 1903 (when the Macduff Harbour lighthouse was put in its present position) but does show a rather rough sea, something that most people in Banff and Macduff will have seen!

The Banffshire Journal reports “the gale commenced very suddenly, about nine o’clock. The wind had been from the south, and, in a very short time, veered round to west-north-west. The sea was very disturbed, and the rain and spray, blown from the crests of the waves, shortened the range of vision seawards.”

Various damages were reported. It was apparently difficult to walk outside, but also unsafe to walk the streets due to the “quantity of slates falling off the roofs of houses”. Various chimney cans were thrown down, and some of the older and more exposed houses in Banff were “a good deal damaged”, and many had water damage from the force of the wind pushing rain inside. A number of trees were blown over, especially reported in Duff House woods.

In 1874 the Bar of Banff was still in place, ie the sand and gravel bank sticking out from the Macduff side of the river mouth, and the sheltered area south of it was used for beaching boats. The wind blew over several herring boats that were on Green Banks, but they were not badly damaged. These nineteenth century pictures show the Bar with some herring boats sheltering (there are some just north of Banff Bridge, on the Green Banks side, in the hand water-coloured picture)

Sometimes of course larger ships like this schooner were beached for repairs, or for building, on Green Banks.

From the national newspapers of the time it seems Banff and Macduff did not get the worst of the weather; further south in places there was more substantial damage. It is reported that every telegraph wire north of Birmingham was out of action!

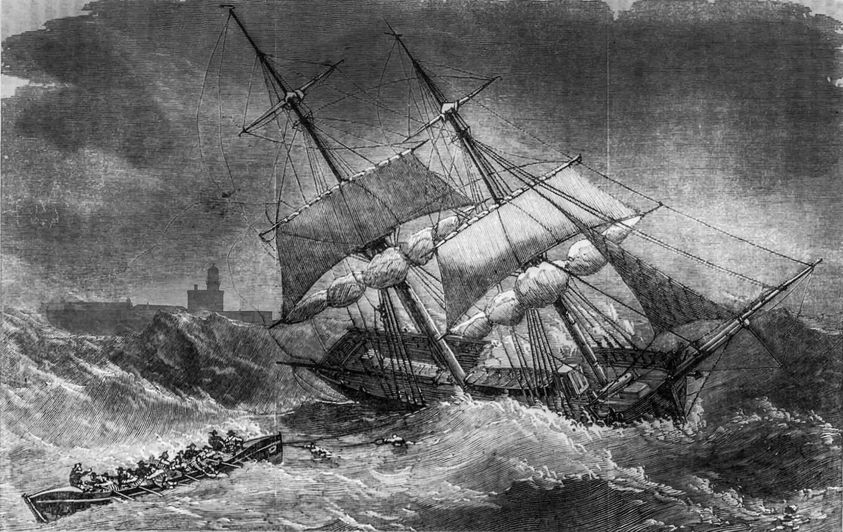

Fraserburgh did have a wreck, of the schooner “Moir”. Her details are not known, but she had sailed from Portsoy with a cargo of oats, bound for Newcastle. But she was blown on to Fraserburgh Sands (just south of the town). Captain James Smith and his crew were saved by the Fraserburgh Lifeboat “Charlotte”. The painting below was done in 1875, the year after, but it is not specified as the “Moir”. The black and white image shows the “Charlotte”, again in action in 1877 for another schooner, the “Fuchsia”, a rescue which saved 4 adults and 4 children.

Were humans in Banff and Macduff 3,000 years ago, or even earlier? It seems they must have been and even back then had an appreciation for the beauty of our countryside.

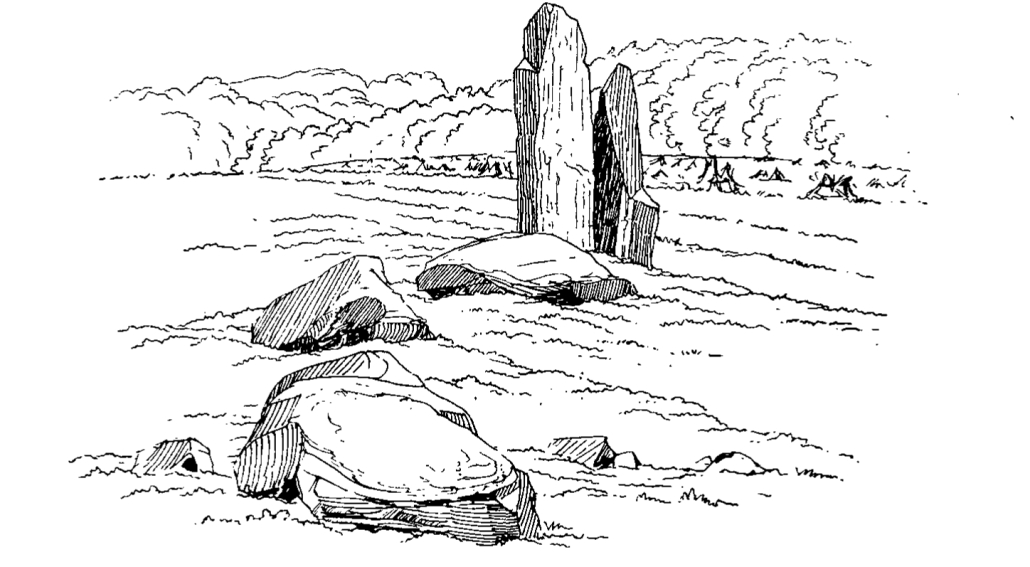

One of the pieces of evidence, about a mile south of today’s Banff Bridge, as a small island in the middle of a large field, there are a few stones, lying at all angles. Today, none can be said to be truly upright.

The first found written record of these doesn’t appear until 1780, described by Thomas Pennant as “several large stone pillars, tending to form a semi-circle, and are doubtless the remains of a Druid temple.” Unfortunately there was no accompanying drawing! The idea of a “Druid” temple, often associated with sacrifices “in honour of immortal gods” was a theory applied to stone circles through to the mid-nineteenth century.

An in-depth survey was conducted in 1903 by Mr Fred Coles and reported in the 1906 Proceedings of the Society of the Antiquaries of Scotland. By this time only two stones were left standing, and an inspection suggested only one of these was in it’s original position – which seems to be the stone most upright today.

Mr Coles concludes that this used to be a recumbent stone circle, ie one stone lying horizontally, with an upright at each end of it – as many such circles can be found in the northeast of Scotland. Unfortunately the Gaveny Brae circle has had stones removed and has been much damaged from “a deplorable want of respect” over the centuries in agricultural districts, a sad fact which Mr Coles much laments.

The position of the site is on a level part of a ridge looking north along the Deveron valley to the Moray Firth – from visiting the site it would seem likely the position was specifically chosen. In 1901 the artist Robert Allan painted the view from seemingly the position of the stone circle, which is very comparable to a more modern view (this one with one stone in shot):

The pillar of smoke or steam just to the right of centre in the Robert Allan painting being a train at Banff Bridge station!

The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland published their detailed review of all the stone circles in north east Scotland in 2011 in their book “Great Crowns of Stone”. By this time the Gaveny Brae stone “circle” is so unlike a circle it is relegated to an eight word reference in “Other Monuments”!

As to the real uses of these “Stonehenges of the north”, perhaps we shall never know. It seems that their use changed over time after being places of worship and sometimes burial sites in the Bronze Age, but less respected as times changed. There is much discussion in the papers of the Banffshire Field Club (available on line) on this subject.

If you are looking to visit the site, on the latest Explorer and Landranger Ordnance Survey maps the Gaveny Brae stone circle is marked as just “Standing Stone”, south of the Distillery; on the previous “1 inch” maps it was labelled “Cairn Circle”, although the obvious mound is believed to be just the result of farming, and not a burial cairn.

On the plus side, at least the Gaveny Brae site is known and marked and visible; another reported stone circle at the top of what is today Strait Path in Banff, the last stone of which was reported as the “Grey Stone”, is supposedly buried beneath the pavement!

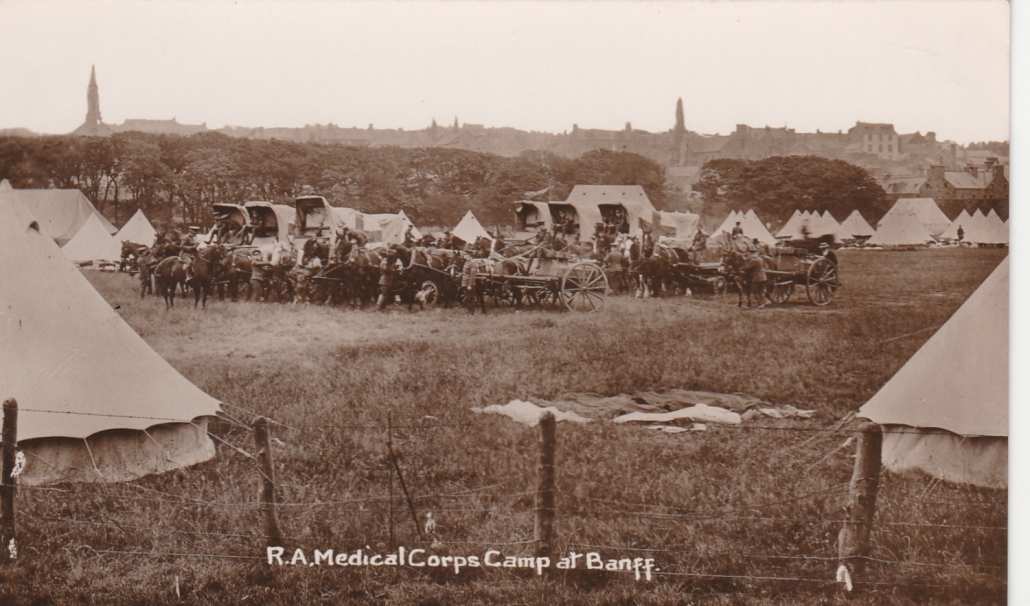

This Story was prompted by the finding of a rare postcard as shown above. The Royal Army Medical Corps used to hold an annual camp, and Banff – specifically Canal Park – was the location in 1912. The Banff skyline really hasn’t changed that much!

Five hundred years ago, Canal Park was a swamp, part of the Deveron estuary. It was drained, perhaps by the influence of the Carmelites in Banff, and has had several uses since. It’s name came from four hundred years ago, at the time of the building of Duff House in the early 1700’s, when a canal was built from Banff Bay to the back of Duff House. The canal was the means of getting the stones that had been carved at William Adam’s works on the Forth, to the building site; brought to Banff Bay often on William Duff’s own ships, and then onto barges to Duff House. Even though the canal no longer exists the name has stuck.

Canal Park was part of the Duff House grounds, the wall now visible just behind the silversmiths, extending along the side of Bridge Road to the gatehouse still existing in the Co-op car park. In 1906 the Duke of Fife gifted the land to the Burgh Councils of Banff and Macduff for recreational uses and it seems much use was made of this Park. In the early 1900’s Canal Park was one large park, including where the Princess Royal centre is today, as well as the football pitch and tennis courts nearer the river, although officially by then the whole area had been designated Princess Royal Park (named from the 1889 wedding of the 6th Earl Fife (1st Duke of Fife) to Louise the Princess Royal, daughter of the future King Edward VII.

In this 1909 image the line of trees at the back of the Park, which are no longer there, is where the road to the Princess Royal centre and Airlie Gardens sheltered housing now is.

By 1912, the Park was under the care of a joint board from Banff and Macduff Burgh Councils. Activities such as the important Banff Cattle Show were held there, and lots of smaller events such as a Fancy Dress parade.

But in 1912 the Trustees received an application from the Royal Army Medical Corps to hold their annual “camp”, partly because it was such a sheltered location, sheltered on two sides by a high wall, and to the west by the line of trees. This was finally agreed, finding enough space for them and the Cattle Show. The camp started on 20th July 1912 although the whole area was only available after the Cattle Show on the 24th ! It seems both were a great success.

18 officers and 231 men came to the camp, with 52 horses. Two special trains were laid on from Aberdeen to bring the bulk of the men and horses, All were living in tents and a special water supply had been laid out across the park for both the men and the horses. The RAMC officers however received their meals at Duff House Hotel !

A number of activities, drills and exercises and demonstrations were laid on, as well as various parades, sports activities and musical events. What the townsfolk felt about the 05.30 Reveille isn’t reported, but generally the RAMC Camp provided a lot of local attention. On 23rd July a major exercise was held on Doune Hill, setting up a field hospital and transporting “injured” personnel.

The camp was made to be inclusive of the town, local people able to come to some of the events, such as the Banff Pipe Band joining the RAMC Corps Band for various parades and concerts; football and tug-of-war matches between RAMC and towns’ teams. Cricket matches were also played with the Banff team; although the RAMC easily won the cricket they were roundly trounced in football !

The RAMC was formed in 1898 to centralise the provision of emergency first aid at the front line, as well as staffing health centres and hospitals and promoting health and disease prevention. The unit still exists today. Their badge – an early 20th century version shown here – has the “Rod of Asclepius” at it’s centre; the Greek God Asclepius of healing and medicinal arts, typically depicted by a non-venomous snake; a similar badge is used by some Scottish Community First Responder teams today. The RAMC motto is In Arduis Fidelis; “Faithful in Adversity”.

Part 2 of 2

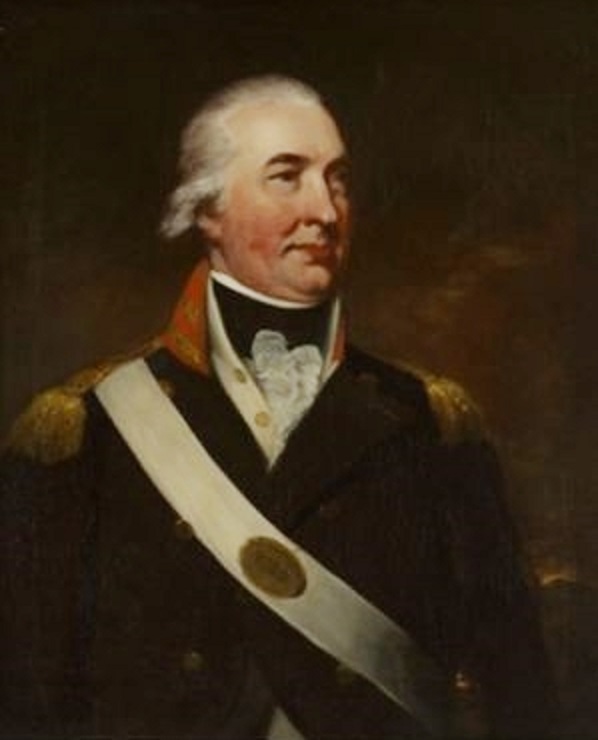

James returned home in September 1813 as the 4th Earl Fife, his father having died in 1811. He was received in Banff and Macduff with huge rejoicing, met by the Magistrates, the principal inhabitants of Banff, the incorporated trades and “all the inhabitants of Macduff”. Flags were displayed at the forts, the shipping, the hills; a salute was fired from the battery and “all the bells of Banff and Macduff rang a merry peal.”. In the evening there were illuminations and immense bonfires in every street, and on Doune Hill there “was one of such extraordinary size and brilliancy as completely illuminated the whole road from the bridge of Banff to Macduff”.

King George IV (as Prince Regent) made him a “Lord of the Bedchamber” (a trusted confidant and advisor), and later – 1827 – conferred on him the “Order of the Thistle” (of which there are only 16 at any time) and the Grand Military Cross of Hanover. James is wearing these insignia in the painting in Duff House’s North Drawing Room. He was also elevated to the British peerage as Baron Fife.

James became the Whig Member of Parliament for Banffshire in 1818, holding it until 1826. He was a keen Mason, becoming the Grand Master Mason for Scotland. In that capacity he laid a foundation stone for Waterloo Bridge in 1815 (opened 1817) and the Regent Arch in Edinburgh (opened 1819) amongst others.

James unfortunately found his resources were substantially curtailed. In 1816 James had to go to court to contest the Will of his uncle, who had left almost everything to his natural son, James Duff of Kinstair. He was ultimately successful, helped by the legal knowledge he displayed, to the delight of his friends and the surprise of his opponents.

During the 1820’s his name was linked to a few actresses, specifically Mademoiselle Noblet, on whom it is alleged he spent a fortune. It was also claimed by some he was the father of Maria Mercandotti, a very pretty dancer and actress he brought over from Spain – but the dates don’t fit with when he first met her mother!

Local good deeds

It is hard to imagine the esteem in which James was held locally, both before and after his almost permanent residence at Duff House from 1833. A very few of the many reasons for him being held in such high regard locally include:

- his support for the local farmers during times of hardship; supplying seed to them and most notably during the potato famine of 1847;

- several improvements and expansions at Macduff harbour; this picture shows men working on the harbour wall in 1842. This added to the prosperity of the town which had been planned by his uncle;

- creating, planning and growing the town of Dufftown (1817), intended to provide accommodation and employment for veterans of the Napoleonic wars;

- paving the pavements of Elgin;

- repaired and renovated much of Pluscarden Abbey;

- building the Fife Arms Hotel on Low St, becoming one of the finest hotels in the north;

- starting a soup kitchen;

- assisting with funds to erect a new church for the Episcopal communion (St Andrews);

- furnishing the County Hall;

- opening the Pleasure Grounds of Duff House to the public for walking and riding;

- developing his lands, planting new trees (including the huge Monkey Puzzle tree in memory of his friend from Spain, the Libertador of Argentine and Chile, Jose de San Martin); this led to the planting one hundred years later in 1950 of the Monkey Puzzle in Banff Castle grounds;

- and his particular delight of seeking out those that needed help. He is said on one occasion to have relieved an aged woman by carrying a sack of meal to her home for her; telling her to sieve the meal well before using it. On her return home she did, and was filled with joy at finding several golden coins.

Apart from his friendship with the King, he had many friends, British and international, and knew most of the key society people of the early nineteenth century. He often had grand parties at Duff House. In 1850, James’s birthday was celebrated (on Mon 7th Oct as the 6th was a Sunday) with flags and decorations throughout the town; arches of flowers were erected at the Fife Arms and Oak Hotel (bottom of Strait Path); even the coaches from Inverness and Aberdeen were decorated with “fantastic and yet beautiful” shapes of flowers. Bells, musicians, guns and mortars entertained a crowd that filled all the space from Bridge St to Greenbanks. There was a huge Ball, held at the Barnyards (now Duff House Royal), another for the youngsters, and a dinner attended by hundreds.

Although enjoying robust health for most of his life, apart from occasional after effects of his wounds from Spain, James took ill in February 1857 and died on 9th March. The Banffie reports that 10,000 people turned out for his funeral. James Imlach, historian of Banff, summed him up as “A warrior and a courtier, a nobleman and a statesman, he rejoiced most of all in the title of the poor man’s friend.”

Part 1 of 2

James Duff – the future 4th Earl Fife – was born in Aberdeen on 6th October 1776 to Alexander, younger brother to James Duff 2nd Earl Fife, and Mary Skene of Skene. The older James, at this stage, realised he probably wouldn’t have a direct heir, and was also somewhat critical of his brother as being “weak”; also his sister-in-law had been described as having “moral laxity and emotional instability” So from the age of 6 our future hero was brought up in Duff House under the care of his uncle, to be groomed as the future Earl Fife. He went to the renowned Dr Chapman’s school at Inchdrewer, and then in 1789 to Westminster School, before going in 1794 to Christchurch, Oxford. However he soon became a student at Lincoln’s Inn and received legal training for three years, which would stand him in good stead in later life.

By 1793 his uncle had described “Jamie” as much “improved”, with “really good principles, and temper, with every prospect of application and good parts”. He had an aptitude for languages, learnt Latin and Greek, and frequently visited the Houses of Lords and Commons. He learnt the style and manner of great public speaking. In 1794 Jamie abandoned his legal studies in London and joined the Allied army on the Continent, fighting against the French Republic. He was present at the Congress of Rastatt, trying to resolve the French occupation of the left bank of the Rhine – until the French resumed fighting in 1799.

Jamie returned to London and on 9th Sept 1799 married Maria Caroline Manners. This was most definitely a love match; the couple enjoyed society living in London and Edinburgh while also spending some time at Duff House. He was appointed to the command of the Banff and Inverness Militia, and he reportedly much improved their discipline.

During a stay in Edinburgh on his militia duties, his wife was scratched on the nose by her pet Newfoundland dog. Not much notice was taken of this incident, perhaps because rabies was only just starting to become known; not even when the dog became bad tempered and bit a groom; the dog was then put down. Within a month however Maria became ill, and although the physicians realised the nature of the malady, it was too late to save her and she died on 20th December 1805 of “undoubted hydrophobia”. She was described as “so well known and so universally esteemed” and was much mourned.

Although James was overwhelmed with grief it was several aspects of his life to date that led to the events that made him a true here. He went back to Europe, joining a combined force of British, Swedish and Prussians, anticipating an inevitable war with Napoleon. Looking for action he shifted to Vienna and joined the Austrian army under Archduke Charles, fighting in battles at Wertignen, Ulm, Munich and others. Even though the French were victorious, James learnt much of military tactics. On hearing of the disturbances in Spain he sailed from Trieste to Cadiz to assist the Spaniards against the French. He learnt Spanish and fought with several of the Junta, but later uniting with an army under Lord Wellesley, later the 1st Duke of Wellington.

He fought at the battle of Talavera in which he was instrumental in moving some guns that then inflicted much damage on the French, and although wounded by a sabre cut to the neck during a counter-attack, still saved the life of a Spanish officer and led a harrying force on the fleeing enemy.

With reinforcements the French soon attacked outposts around Cadiz, and during the battle of Ocana, James was badly wounded while going to the successful aid of a beleaguered fort. The Madrid Gazette said “Lord Macduff and Colonel Roche are the active and indefatigable agents of England with the Spanish armies.” James received much praise and recognition, even if his name was pronounced “Maucdoov” ! He soon recovered and took an active part in many other battles.

Meanwhile, in 1811 his father had died and James had become the 4th Earl Fife, and he prepared to head back to Scotland. Lord Wellesley presented him with a magnificent Damascus sword, ornamented with precious stones on a ground of solid gold, to mark his meritorious services.

The Cortes Generales, the Spanish Parliament, not only made him a General but also a Knight of the Order of St Ferdinand, Spain’s highest gallantry award – their equivalent to our later Victoria Cross. On paintings of him after 1813 he is wearing this medal.

James later life and the good deeds he did around Banff and Shire are in Part 2 of his story to follow.