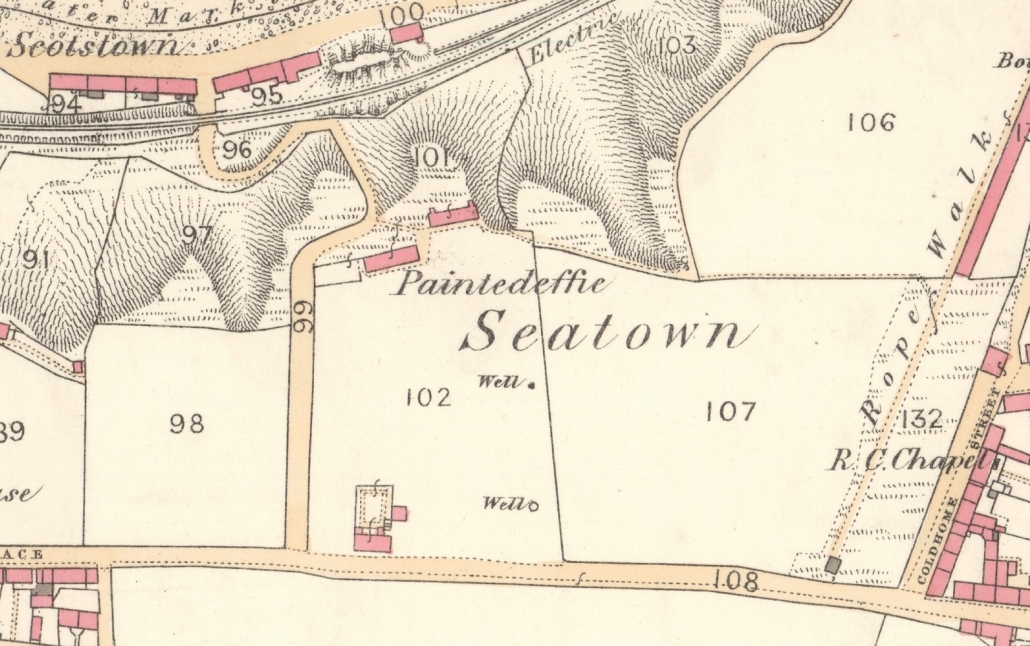

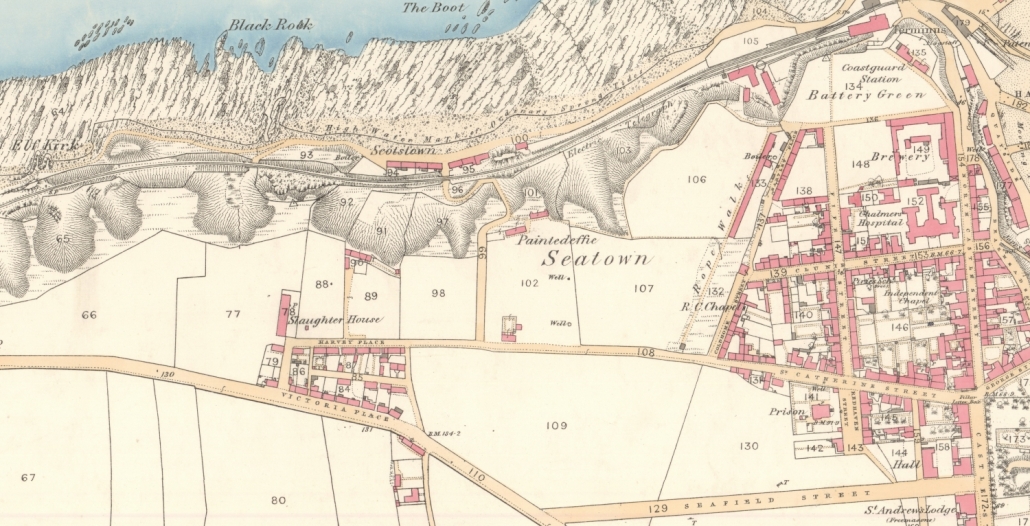

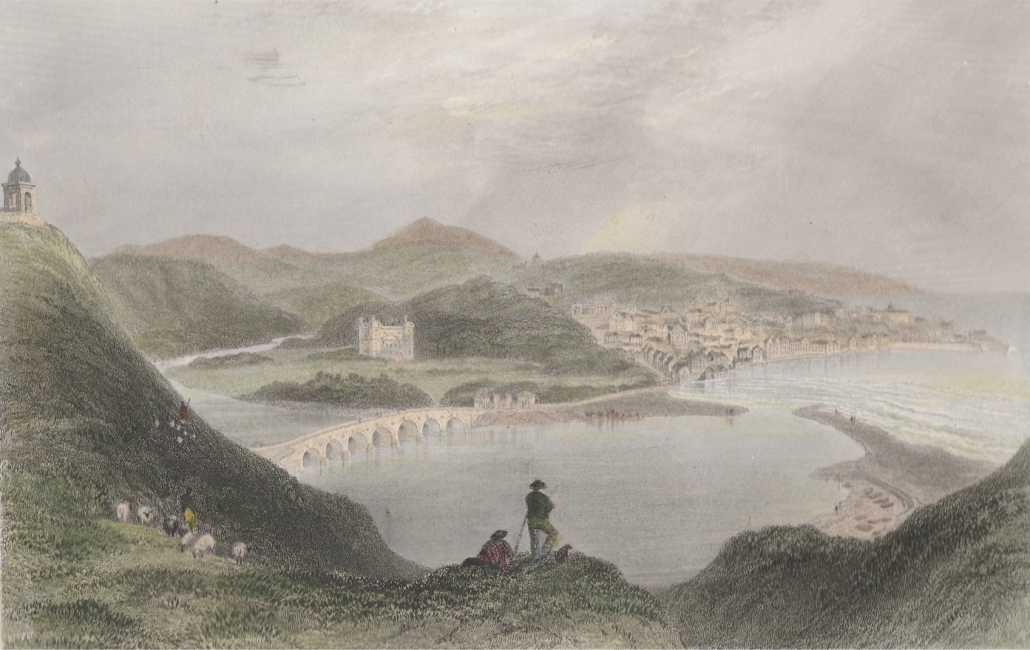

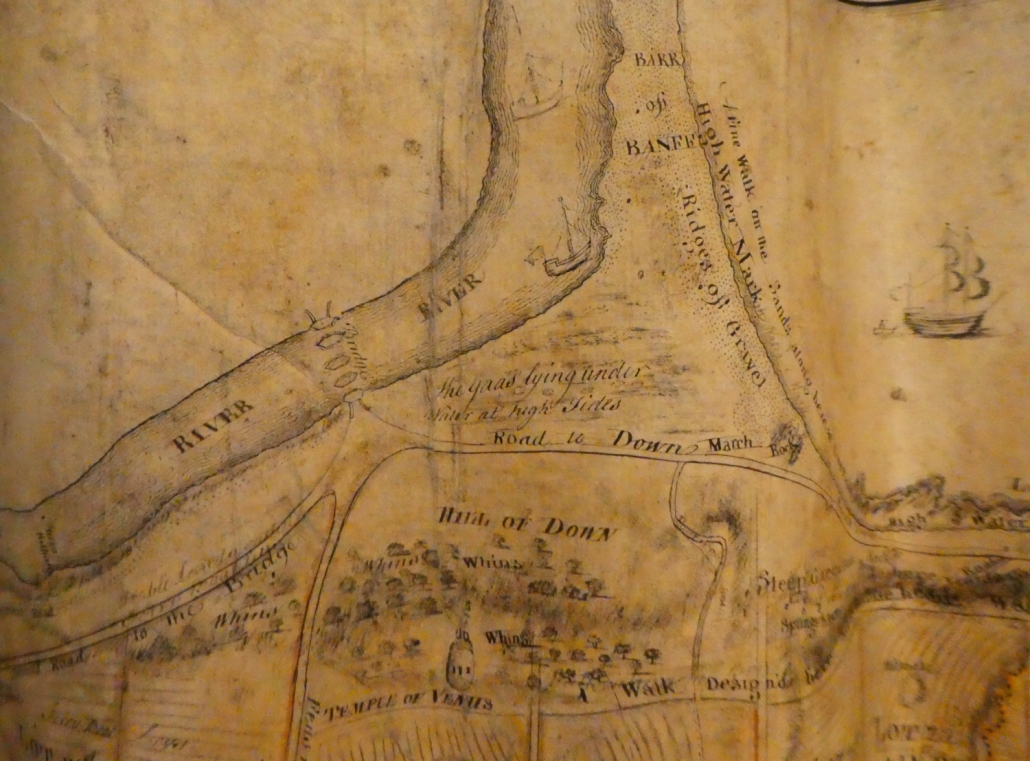

Low Street, Banff. The first mention of a hotel on Low Street is 1773, when Samuel Johnson and James Boswell visited, hoping to meet with the Earl Fife, but he was not at home. Apart from Samuel Johnson’s many literary works, it was in his Journey to the Hebrides that he recounted a story of his stay at the Black Bull Inn, and how the practice of not being able to hold windows open seemed to get him riled up! This map of 1775 shows the layout of Low St as it must have been when Boswell and Johnson visited.

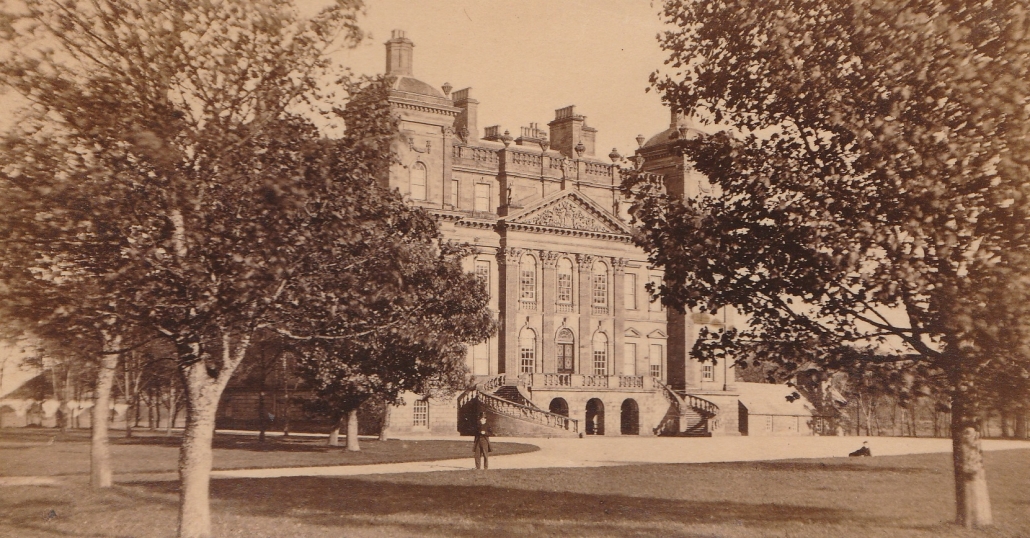

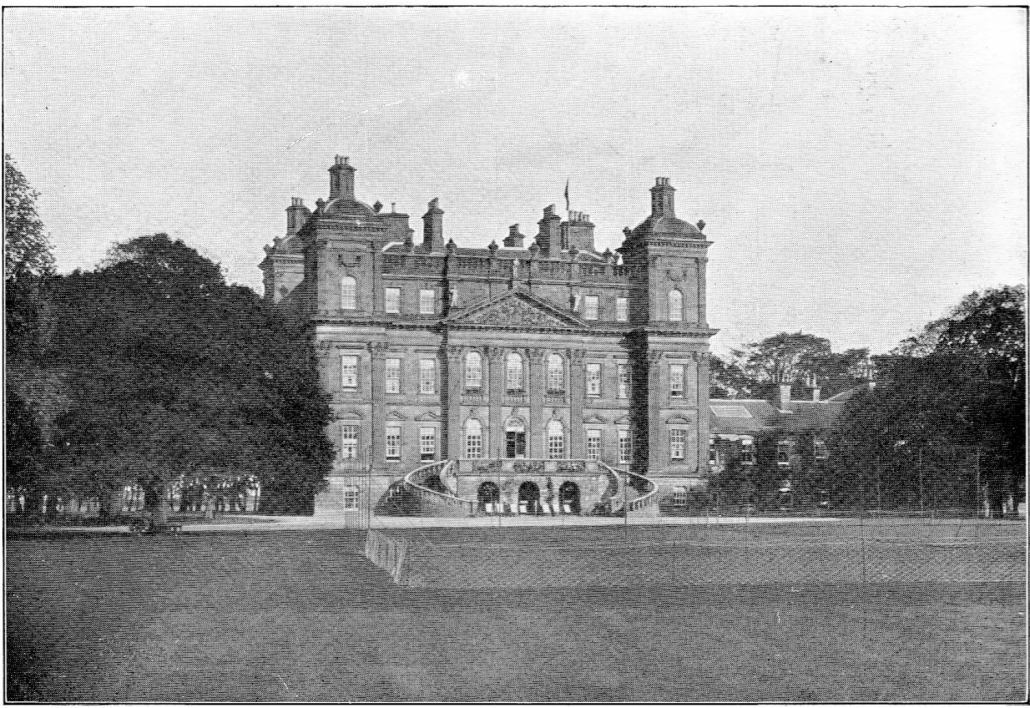

But in 1845 the Black Bull Inn was no more. The Duffs had built a new building between 1843 and 1845 for the purpose of providing more space for visitors to Duff House; operating it as a commercial – and very successful – hotel: The Fife Arms Hotel. This is the building that we see today – including it’s stables, but the gardens behind have since been built over.

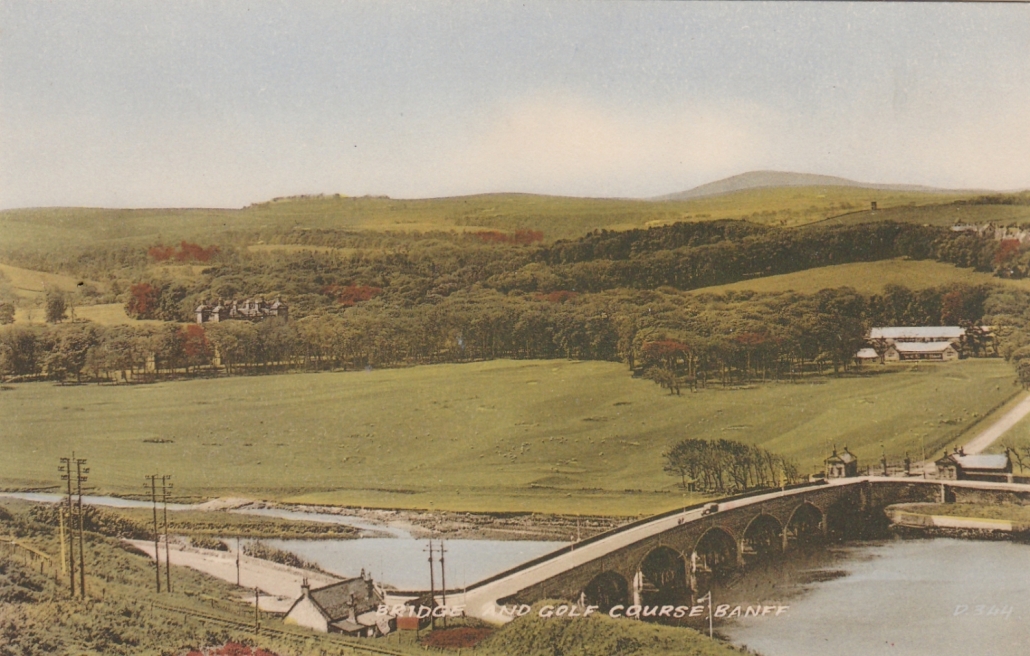

The hotel was slowly equipped to be one of the leading hotels in the area “affording ample accommodation for all classes of travellers”. The trade became so busy that in 1858 Mr Marshall the manager, invested in “a large number of first-class horses and new vehicles” including “Carriages, Broughams, Omnibus, Dog-Carts and Gigs” that “is not surpassed in the North”. The cellar was stocked with first class wines and liquers of every description. The hotel itself ran coaches to the rail stations at Huntly, Elgin, Aberdeen and Peterhead from 1858 (the Banff station didn’t open until 1859, and Banff Bridge – Macduff – 1860). There were 39 bedrooms with a permanent staff of 16, rising in the summer to about 25.

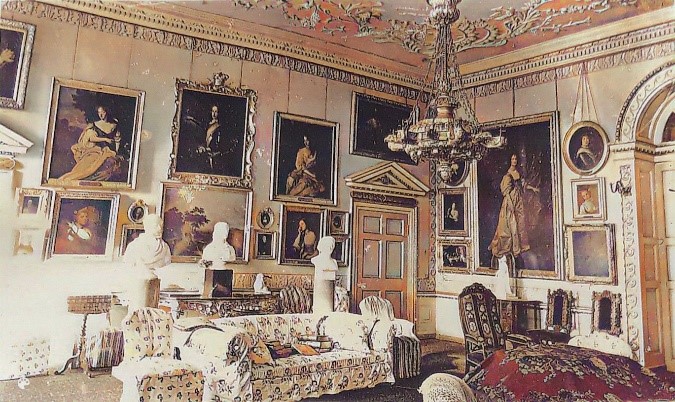

We know the Lord Fife’s used the Fife Arms hotel from time to time, not least from a diary written and published by Elizabeth Pennell, an American authoress, who stayed there in 1888 (see separate Heritage Story).

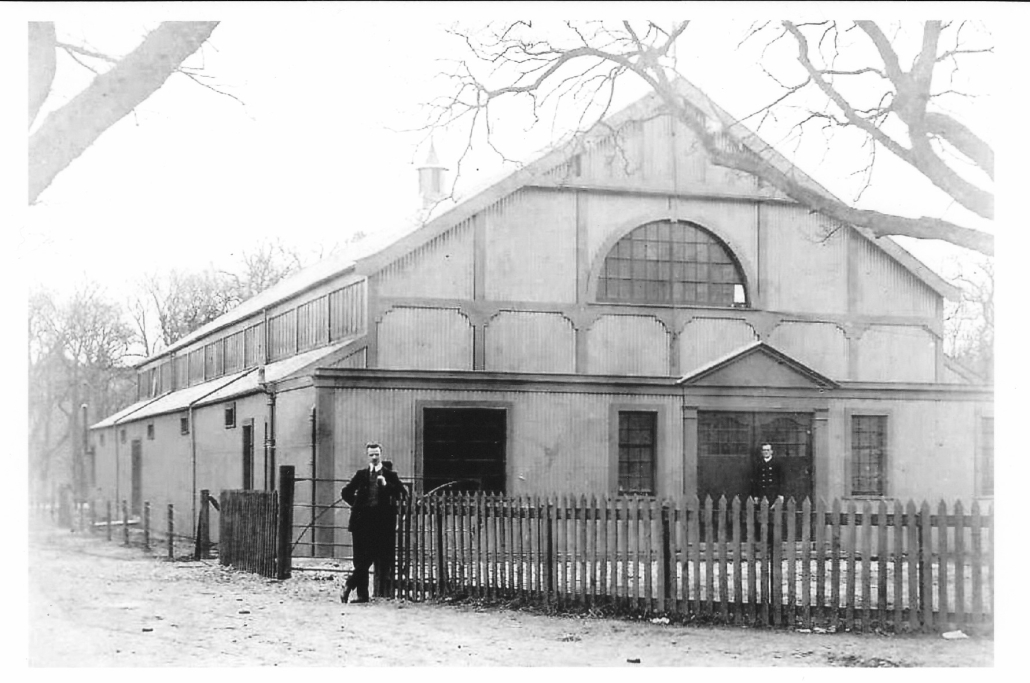

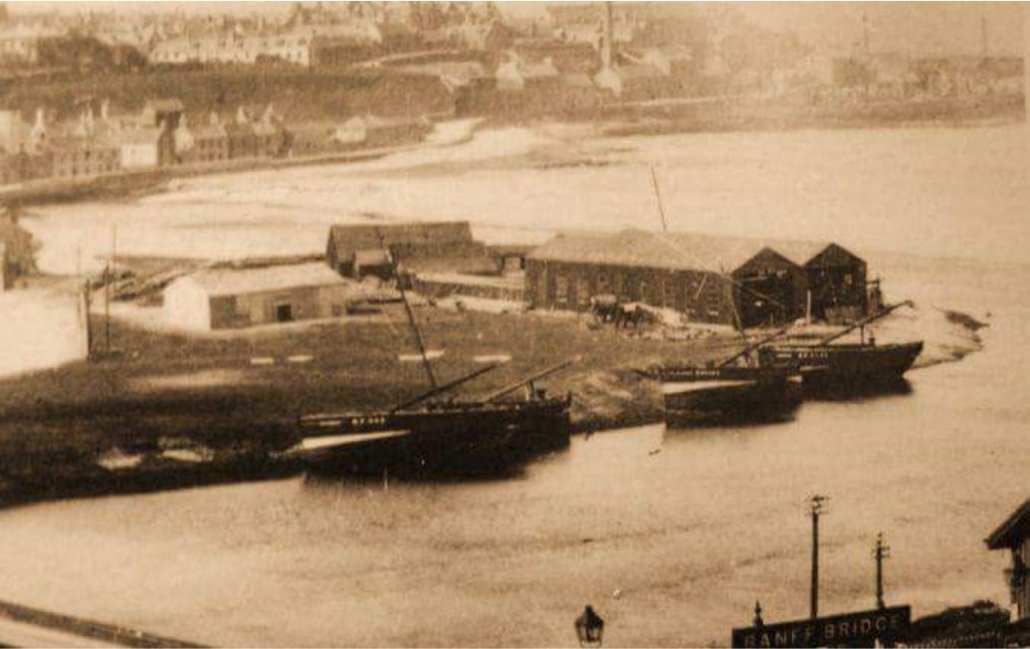

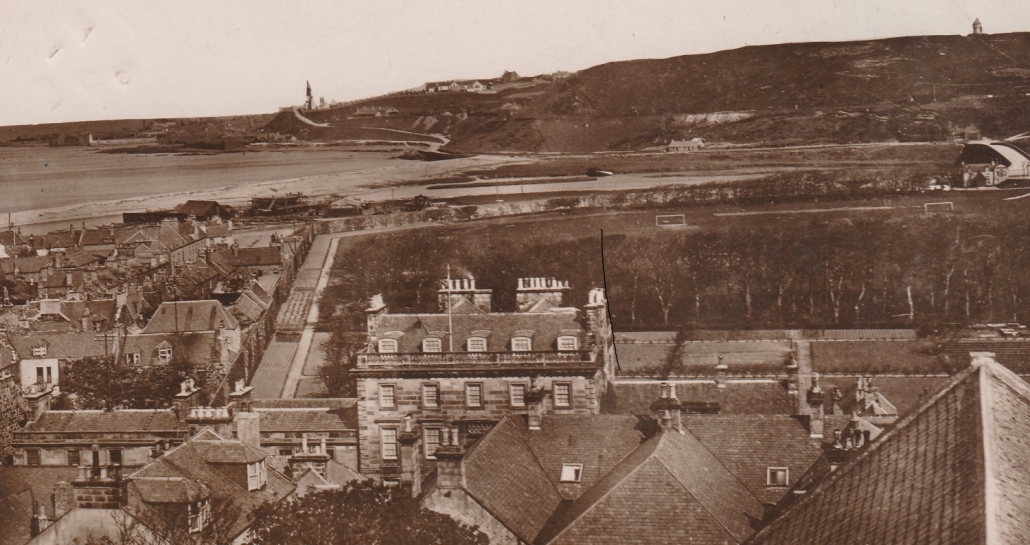

There were gardens behind the original hotel but these were the Kitchen Gardens for Duff House. The 1873 Gardener’s Diary makes several mentions of interaction between the gardeners and the maids at the back of the hotel! This postcard excerpt, sent in 1913, shows some of the layout of the Duff House Kitchen Gardens behind the hotel.

These gardens do not appear to have been part of the gift to the towns by the 1st Duke of Fife in 1906; the 2 acres, including a greenhouse, remained in the ownership of the hotel, and were re-laid out in 1916. In 1919 the hotel was taken over by Trust Houses – later Trust House Forte – adding an extension at the back in 1920. A Mrs Simpson was manager from 1923 until at least the late 1950s. One of it’s selling points was that it also owned a stretch of the River Deveron for private fishing, much advertised in newspaper adverts around the whole of the UK.

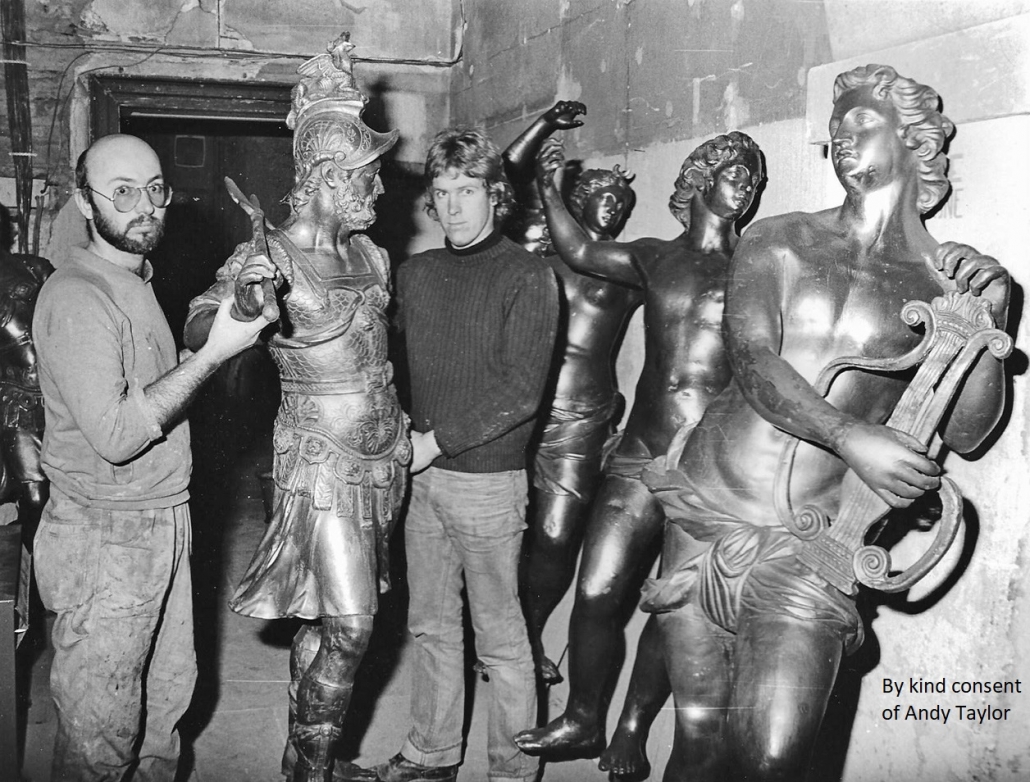

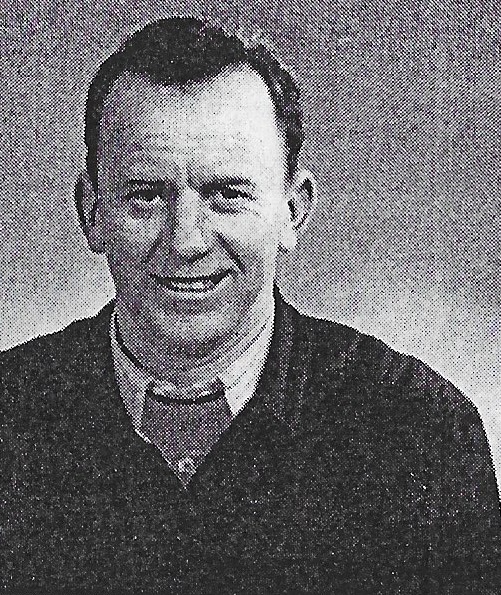

The gardens grew virtually all the vegetables needed by the popular hotel, as well as a flower garden, where guests could take a stroll or have wedding pictures taken. Alexander Duncan, more commonly known as Dougan, had started work there in 1936, becoming head gardener, with his nephew as his apprentice, from 1946, taking over from Alexander Craib. Dougan turned the garden into a prize-winning one – reported as 60 prizes in 1957; not considered bad for the most northerly garden of the Trust House network! This photo shows the Fife Arms Hotel garden in 1957.

The hotel was closed on 29th October 1966 due to the cost it would have taken to upgrade its fittings to match modern standards. It did open again as a hotel under private ownership, from 1968 to the early 80’s, after which from 1982 it was owned by Deveronvale Football Club to be run as their social club. This only lasted to the mid-80s when it was sold again and was converted into flats in 1988. The hotel gardens in 1985 became what is today mostly Airlie Gardens housing.

+++

Connected with the above story, we thank Sonia Packer for information about her uncle Dougan:

Mentioned above as Head Gardener at the Fife Arms from 1946, is Alexander Duncan, born 1920 in Alvah, generally known as “Dougan”. His story shows a stalwart of the town. He started work in the gardens of the Fife Arms aged just 15 and learnt his skill from Alexander Craib who had laid out the garden for the hotel, and from whom he took over in 1946. For at least part of the war he was in the RAF on operations on Lancasters. This photo is Dougan in 1957 while Head Gardener at the Fife Arms Hotel. He left in 1965 when the Hotel was destined for closure.

Dougan was also a player for Deveronvale and later was the much praised groundsman at Princess Royal Park; he was awarded two testimonial matches, 1986 and 2002. Football was not his only sport, and both he and his wife Mary (married 1950) were keen badminton players. For his retirement in 1985 he was given a set of golf clubs by Aberdeenshire Council. Having joined them in 1965 being responsible for all the parks and gardens in Banff, ten years later when the Council re-organised he was appointed area supervisor with the Leisure and Recreations Dept covering the area from Sandend to Rothienorman, Fyvie and Gardenstown. He also served for 21 years as a fireman, rising to sub-officer with the Banff team, retiring in 1981 with a good conduct medal.

After he was widowed Dougan lived at Airlie Gardens – the land he used to tend – until he died in 2007 at the age of 86.

Thanks and acknowledgements for this Story go to:

Sonia Packer for her input about her uncle Dougan;

The British Newspaper Archive and D C Thomson & Co;

National Records of Scotland.