James Duff was born in 1729, the second son of the 1st Earl of Fife. He became the 2nd Earl when his father – William – died in 1763, but it seems he was active in the running of the Duff estate well before that – it is well known that his father was not enamoured with Duff House, even though he had had it built!

30 years after he started developing the Duff House estate, James wrote about some of his agricultural work. He describes the estate with its “many natural beauties from sea views, a fine river, much variety from inequality of ground, and fine rock scenes in different parts of the river; but there was not a tree, and it was generally believed that no wood would thrive so near to the sea coast.”

In other words the area around Banff and Duff House in the first half of the 18th century used to look substantially different. The whole valley had no trees, which must have made Duff House itself really seem to be imposing. Difficult to imagine now, but it shows how the whole lower Deveron valley is a man-made landscape.

James Duff carries on to make it clear that he has proved over a thirty year period from about 1750 that the general belief that trees would not grow so near to the sea coast, was a mistake. In 1787 The Duff park was fourteen miles round, and James claims he has every kind of forest tree, from thirty years old, “in a most thriving state; and few places better wooded”. This was confirmed by some of the well known visitors to the estate.

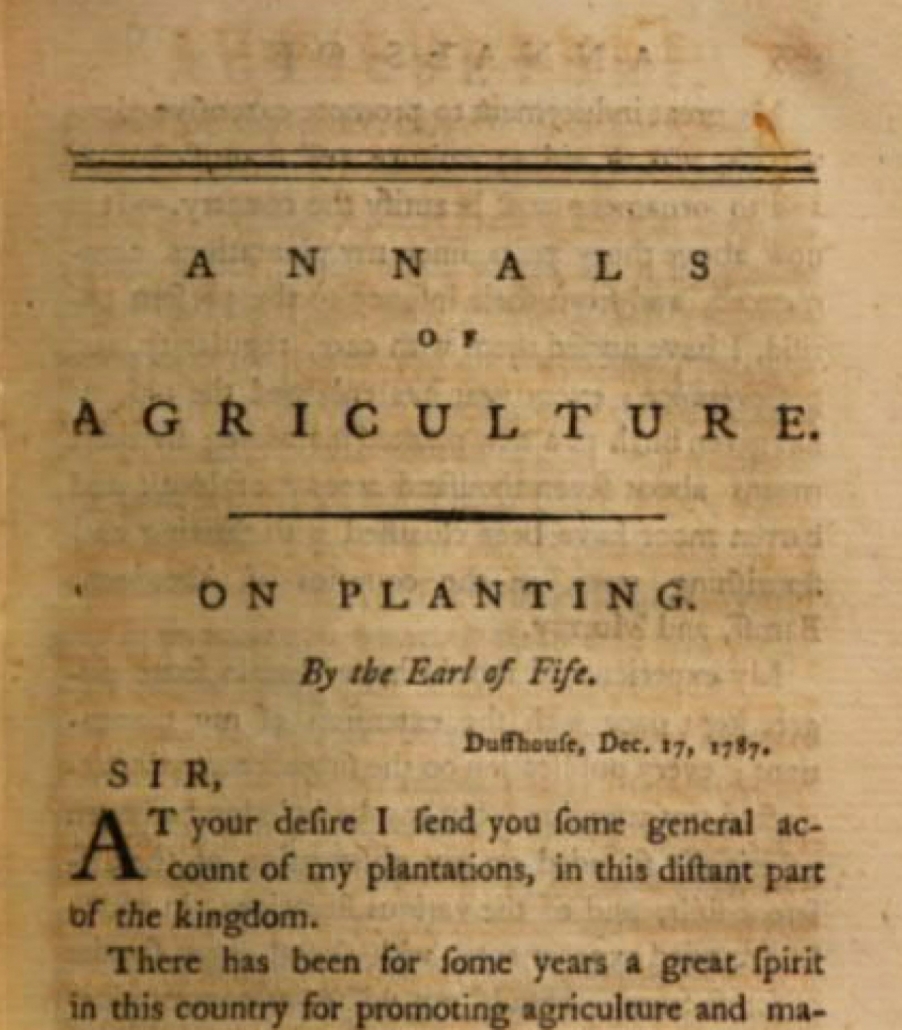

James writes the above in the “Annals of Agriculture” and over several pages goes on to explain in some detail how to grow trees where the climate is not favourable, and in different types of ground. How experience has taught him what species to mix for success, that the best planting density is 1200 trees per acre. He used to bring trees on, mainly in his own nurseries, for three years and then plant them out, mostly amongst “Scotch Firs” as “nurses”.

In this way James planted 7,000 acres mainly in his Duff and Innes estates – as the magazine editor comments “This is planting on a magnificent scale indeed!”. He says that part of his purpose is to provide wood to the local population – all those Scotch Firs that were cut down once the other trees were established – as coal was so expensive in this region, and made worse by “a heavy and unjust tax on it”!

His article prompt considerable interest and many questions; he writes answers to every question and does not seem to hide any detail.

It is clearly because of James’s foresight that we are lucky enough to have such a pleasant Deveron valley, with it’s wooded river-side walks to enjoy.

A. Lyon

A. Lyon