At the present time, in the Grand Salon in Duff House, is a magnificent Christmas Tree, helping to create a festive and relaxed atmosphere within Duff House. Many thanks to the Friends of Duff House.

However it seems it may be only a pale reflection of the tree that stood in the same room 155 years ago, in 1868. This was at the behest of James the 5th Earl Fife and his Countess, Agnes. Not only that, they held a party with numerous guests, in the manner of what was becoming a tradition in Victorian times; those invited were not just the Duff family but all the servants from the House and the estate, including all their wives and families.

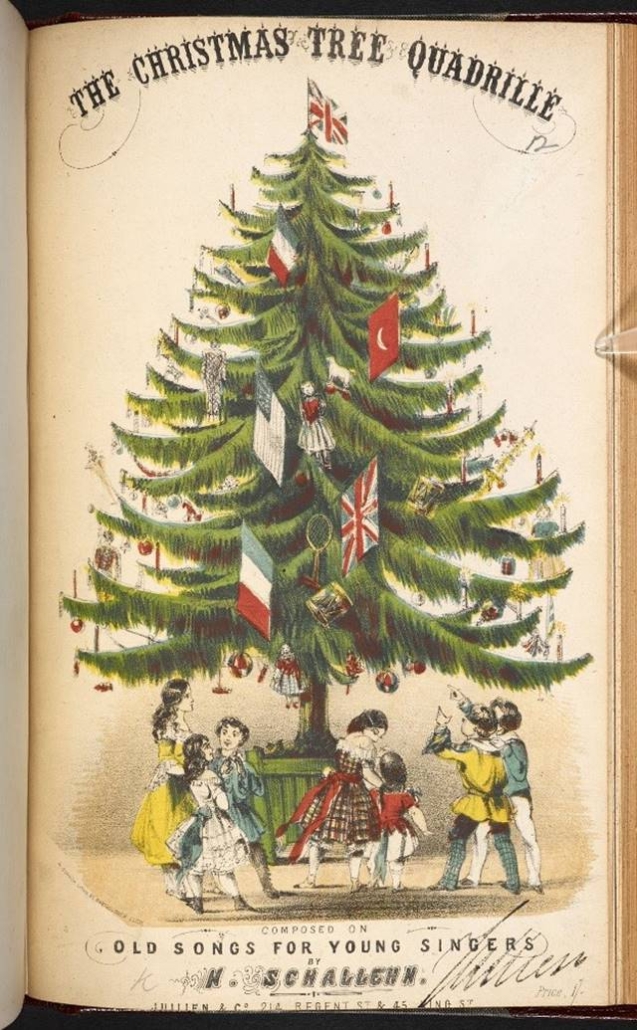

The magnificent and beautiful tree was “prettily decorated with flags and loaded with a multitude of presents”. Having a Christmas Tree was a practice introduced by Prince Albert in circa 1840, bringing the tradition of several decades from his native Germany. The drawing above of the Royal Family’s Christmas Tree was published in 1848 in the Illustrated London News – the first known picture of a Christmas Tree in the UK. The idea quickly caught on around the country.

The inclusion of flags as part of tree decorations was not just a Duff House practice at the time, but is illustrated on this cover below from the 1860s. The Duff family was clearly right on trend!

Music for the occasion was provided by Lady Alexina Duff, aged 17 at the time, on a harmonium; and some solos were sung by one of the servants.

But what made the occasion so special it seems, was the effort taken by Lady Agnes and three of her daughters, Anne, Alexina and Agnes (it seemed they liked names beginning with “A”, also having an Alice and Alexander – later the 6th Earl Fife and first Duke of Fife!) to choose presents for each of the individuals at the party, all piled high under the tree. Each present was wrapped – a practice introduced from America in the 1850s, and each had a name on it – one for every guest. The servants got dresses or articles of clothing, children had toys or books all chosen specifically for the person; “not a few of the presents were valuable and costly” said the Banffshire Journal.

Then there was a sumptuous supper served (not sure by who!) and at midnight Lord Fife gave a speech. The news he gave was that he, his wife and son, Lord Macduff, loved living at Duff House and would spend as much time there as they could – which was greeted by cheers and applause. He also gave the news that an extension would be built on the west side of Duff House, with the work starting in February 1870 – the wing that we now know was bombed in 1940 and no longer exists above ground (except for the war memorial).

Ian Williams

Ian Williams