Strait Path Banff

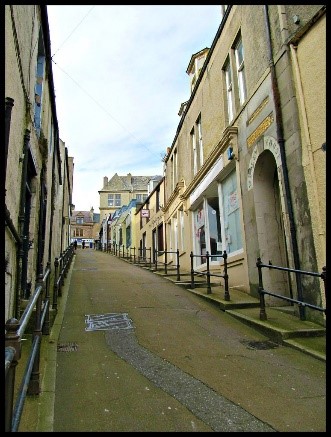

When visitors hear a Banffer mention ‘Strait Path’, they hear ‘Straight Path’. When they look up or down the path this spelling is confirmed; the path which leads from the High Street to the Low Street, is indeed (more or less) straight. However, straightness was not the most salient feature in the naming of the path; it was the narrowness of the path that caused it to be named ‘Strait Path’. Notice both parts of the name imply narrowness; a strait is narrow, as is a path. They could more simply have named it ‘Strait’, or ‘Path’.

There is a third dimension, height, which should have been salient to the namers of Strait Path; the Ordinance Survey puts its elevation at 13.91%. To appreciate this number you only have to stand on Low Street, look up to the top of Strait Path and be awe struck by the very steep climb. Standing there you can readily appreciate why Strait Path featured on the BBC’s website, ‘Is this Scotland’s steepest Street?’. You might also agree that Strait Path could have’ been more appropriately called ‘Strait Hill’.

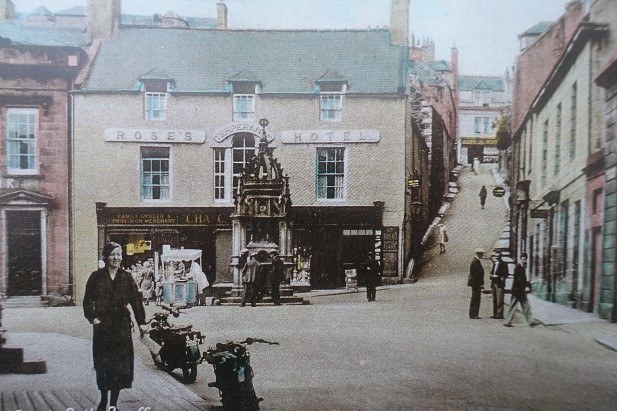

Not everyone is distressed by the climb. Shopkeepers are happy to see people come up the hill, stop for a rest, and have a look at their shops. The local council kindly erected stout railings to provide a support to lean on at various points in the climb. That being said, it is not uncommon to hear visitors say, one to another, with what one assumes is ironic understatement: that brae is a bit steep. The same visitors would find it hard to imagine that up to the 19th century Strait Path was a part of the main route in and out of Banff.

For the most part the kind of shop on Strait Path has not changed much over the years; where you had a barber, now you have a beauty salon, and kilt makers have given way to tailor alterations. As the French proverb has it: things change to remain the same.