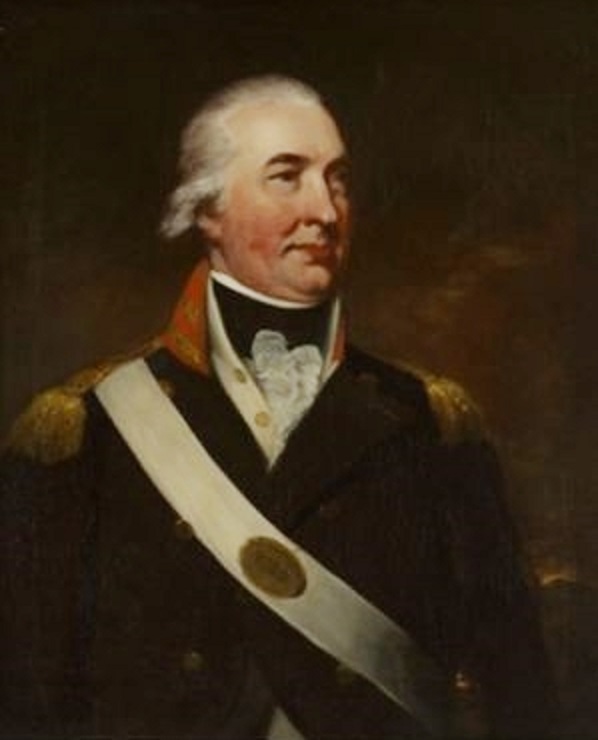

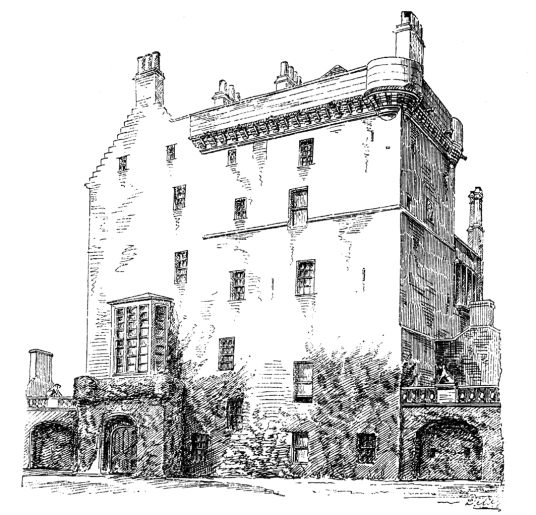

The First Earl Fife who had Duff House built but never lived in it, instead used Rothiemay House as his main residence. He developed and extended both the House and particularly the grounds, as is shown on General Roy’s Map of 1747.

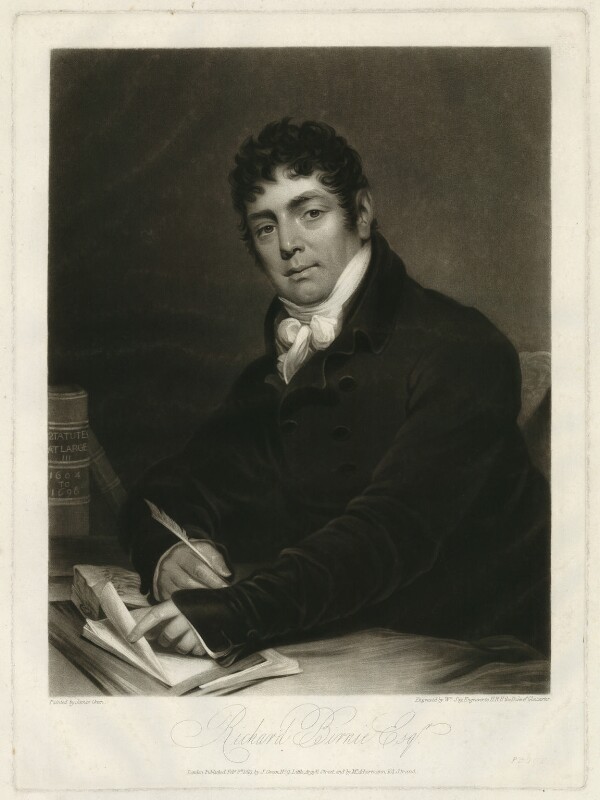

As with many other families he had many children, 14 of them, seven sons and seven daughters. The seventh offspring, the fourth son, was named George. He was educated in Edinburgh and then St Andrews. He had two years from the age of nineteen in the 10th Regiment of Dragoons but had been given education by his father with a commercial future in mind.

Shortly after leaving the Dragoons he married Frances Dalzell, daughter of General Dalzell; apparently they kept the marriage secret for several months but the Duff family letters don’t give a clue as to why. George lived in London for many years because Frances didn’t want to come to Scotland!

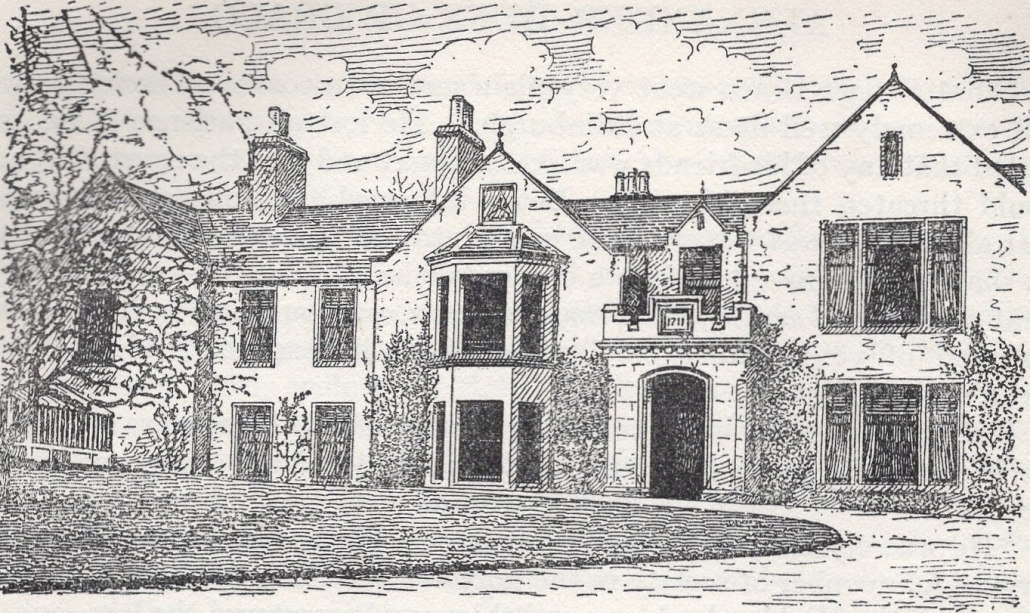

They had four children, the youngest of which was Frances; she was born 26th June 1766 in Elgin. She became the “family pet” and while her mother may not have liked Scotland, “Little Fan” was mostly brought up by her paternal grandmother, Lady Fife, wife of the First Earl, at Rothiemay. A painting of Rothiemay House was made in 1767, much as Little Fan must have known it.

Little Fan seemingly was a very beautiful, well mannered and agreeable child; but she was a delicate child, even catching smallpox at one time, and in 1777 had jaundice. The letters indicate that her appetite was always small. In various letters she is referred to not just as “Little Fan” or “Lady Fan”, but even as “Miss Monkey”. Her uncle Arthur (son of William, First Earl Fife) was a particular favourite and they frequently corresponded, but Little Fan was clearly much admired, even by a previous handmaid of the Countess (Little Fan’s grandmother) who wrote “a charming and young creature”.

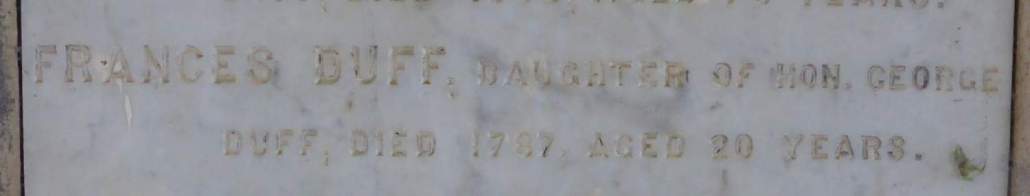

We know of at least two suitors; “Bob” who has not been traced, and also James Urquhart, but nothing was to become of these as she suddenly died, aged just 20, on 6th March 1787. Although initially interred at Grange (near Huntly) she was moved to the Duff House Mausoleum – perhaps because she was a family favourite.

BPHS

BPHS