Today the River Deveron heads in a fairly straight line into Banff Bay, but it used to divert west and run along the sea wall of what is today Deveronside, in 1906 nearly destroying some properties.

This Story was written while looking out the window at a wet and windy day. Almost 149 years ago to the day, there was an even worse storm, described nationally as a hurricane.

A Banff eyewitness described it as “Most awful rough day, a real hurricane and raining too”.

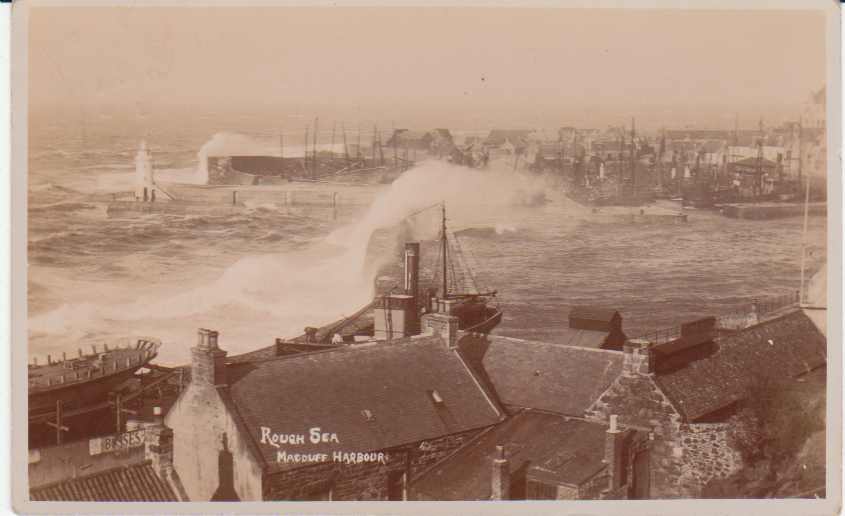

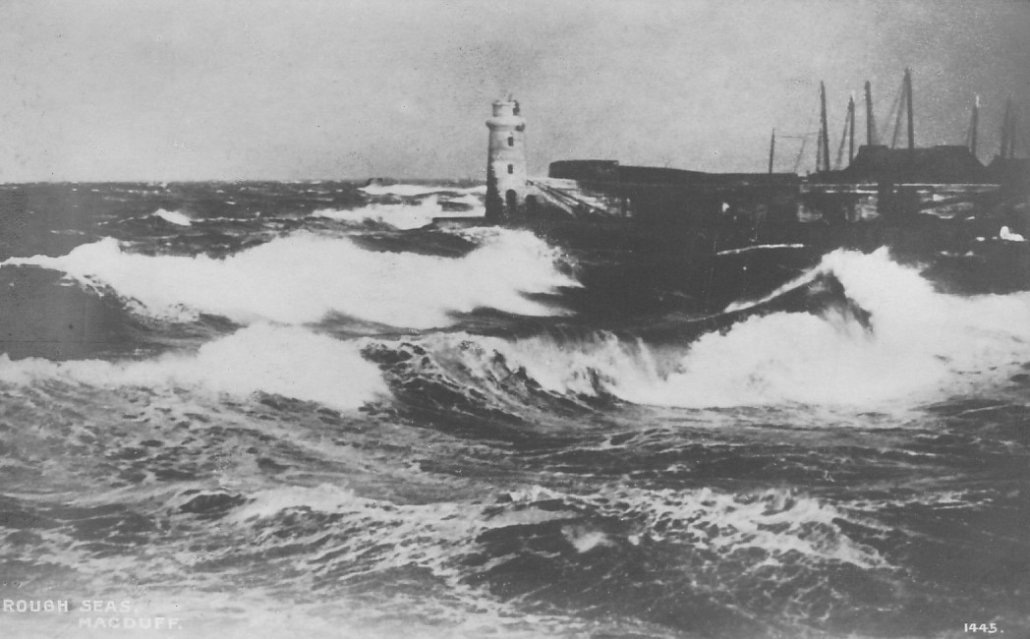

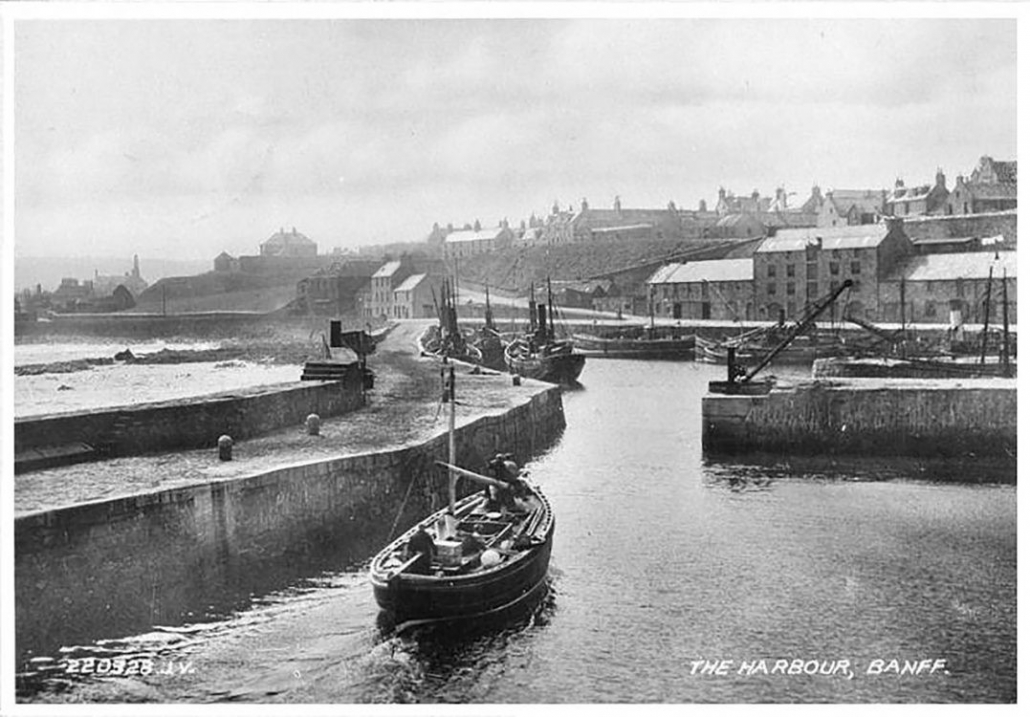

This photo was taken after 1903 (when the Macduff Harbour lighthouse was put in its present position) but does show a rather rough sea, something that most people in Banff and Macduff will have seen!

The Banffshire Journal reports “the gale commenced very suddenly, about nine o’clock. The wind had been from the south, and, in a very short time, veered round to west-north-west. The sea was very disturbed, and the rain and spray, blown from the crests of the waves, shortened the range of vision seawards.”

Various damages were reported. It was apparently difficult to walk outside, but also unsafe to walk the streets due to the “quantity of slates falling off the roofs of houses”. Various chimney cans were thrown down, and some of the older and more exposed houses in Banff were “a good deal damaged”, and many had water damage from the force of the wind pushing rain inside. A number of trees were blown over, especially reported in Duff House woods.

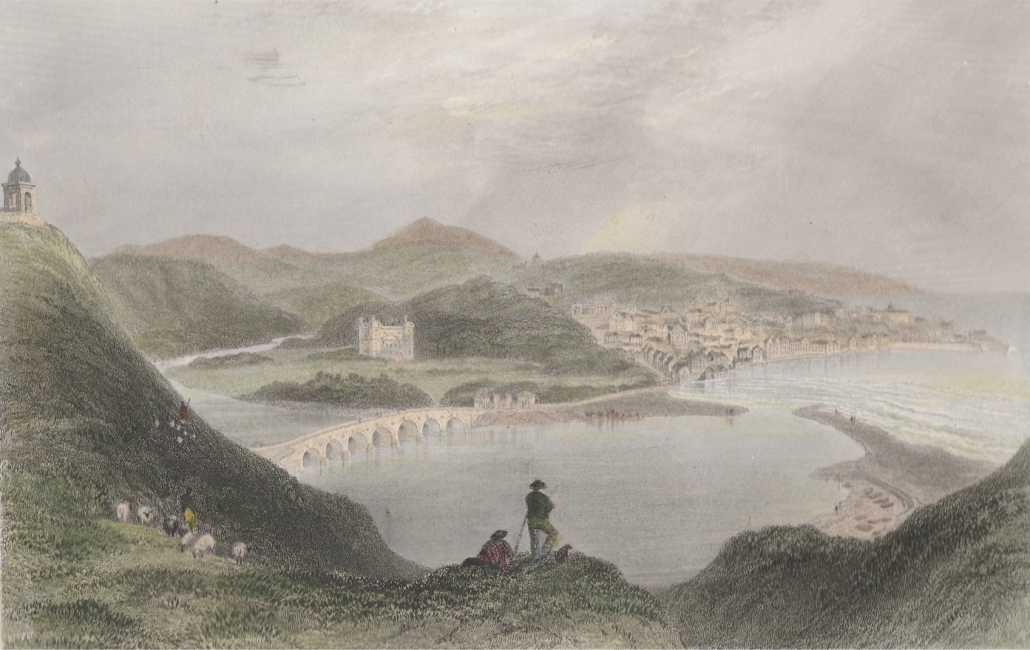

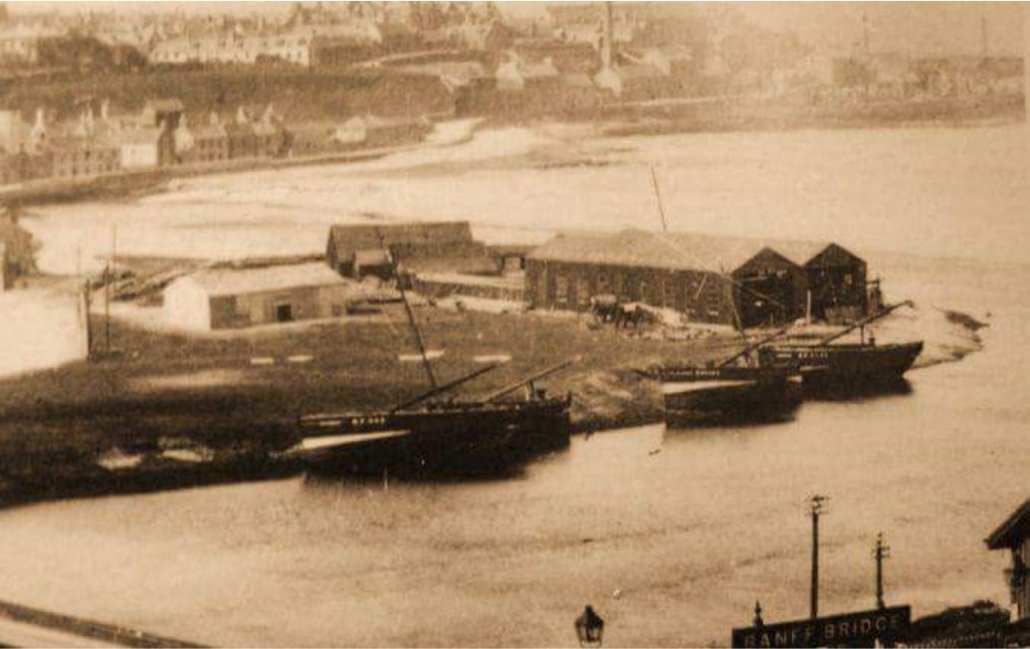

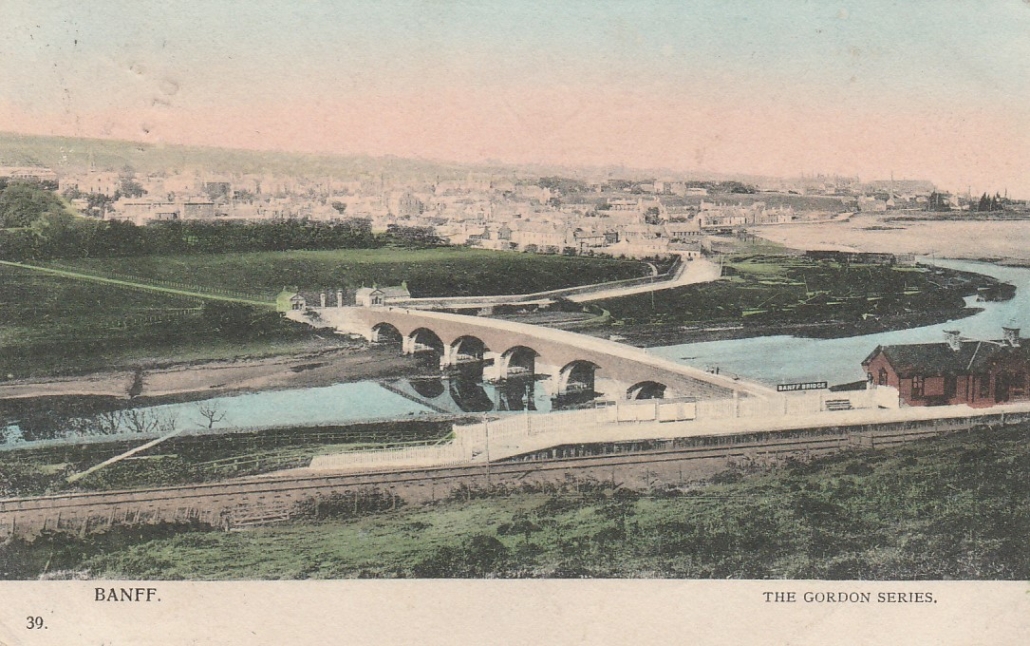

In 1874 the Bar of Banff was still in place, ie the sand and gravel bank sticking out from the Macduff side of the river mouth, and the sheltered area south of it was used for beaching boats. The wind blew over several herring boats that were on Green Banks, but they were not badly damaged. These nineteenth century pictures show the Bar with some herring boats sheltering (there are some just north of Banff Bridge, on the Green Banks side, in the hand water-coloured picture)

Sometimes of course larger ships like this schooner were beached for repairs, or for building, on Green Banks.

From the national newspapers of the time it seems Banff and Macduff did not get the worst of the weather; further south in places there was more substantial damage. It is reported that every telegraph wire north of Birmingham was out of action!

Fraserburgh did have a wreck, of the schooner “Moir”. Her details are not known, but she had sailed from Portsoy with a cargo of oats, bound for Newcastle. But she was blown on to Fraserburgh Sands (just south of the town). Captain James Smith and his crew were saved by the Fraserburgh Lifeboat “Charlotte”. The painting below was done in 1875, the year after, but it is not specified as the “Moir”. The black and white image shows the “Charlotte”, again in action in 1877 for another schooner, the “Fuchsia”, a rescue which saved 4 adults and 4 children.

This was soon after the 1914-18 war. The mortars went off at the coastguard station. My pal said: “Come on, we’ll get a badge”. So off we set at a run for the lifeboat station, then sited at the Macduff end of Banff Bridge. Arriving there we found the skipper throwing out armbands, the badges I mentioned. Of course a couple came our way, which meant we were to tail on to one of the ropes with which the boat was hauled to the launching place, in this case Macduff Harbour. The actual crew were all volunteers but all of them were seamen.

The boat, named George and Mary Berrey, was fitted with oars and sail only, and sat on a wheeled launching carriage. We were soon on our way, and when we arrived at Macduff, the crew all got on board. Mr Paterson, the harbour master, directed operations. There was a kind of slip, a very narrow passage, which the boat had to enter in order to be launched on an even keel, and this proved very difficult to accomplish. Skipper Dowffie (his nickname, not his surname) becoming impatient, shouted to “dump her ower the pier,” but Mr Paterson objected, saying it might damage the keel.

“Fit’s a coat o’ paint fan men’s lives may be at stake” was the answer he got, and we got a shout to let her go. Whoever worked the release pin did just that, and the boat plunged off the pier bow first, went well underneath the surface, and bobbed up again like the proverbial cork. A complete ducking for a start did not in the least dismay the bold skipper and his crew. The boat was well on its way when it was recalled. It had all been a false alarm!

When we arrived back at the lifeboat shed, the boat was housed and everything made shipshape. We handed in our armbands and a sum of four shillings [20p] was paid to each of us hauliers – very welcome for the little we did.

This story is almost word for word from Memories of My Young Days in Banff by A.R. in the Banffshire Journal Annual for 1965. He spelt the boat’s name George and Mary Berry, but I’m trusting the RNLI plaque in Banff Museum. In 1923 they closed the lifeboat station at the bridge and moved it to Whitehills.

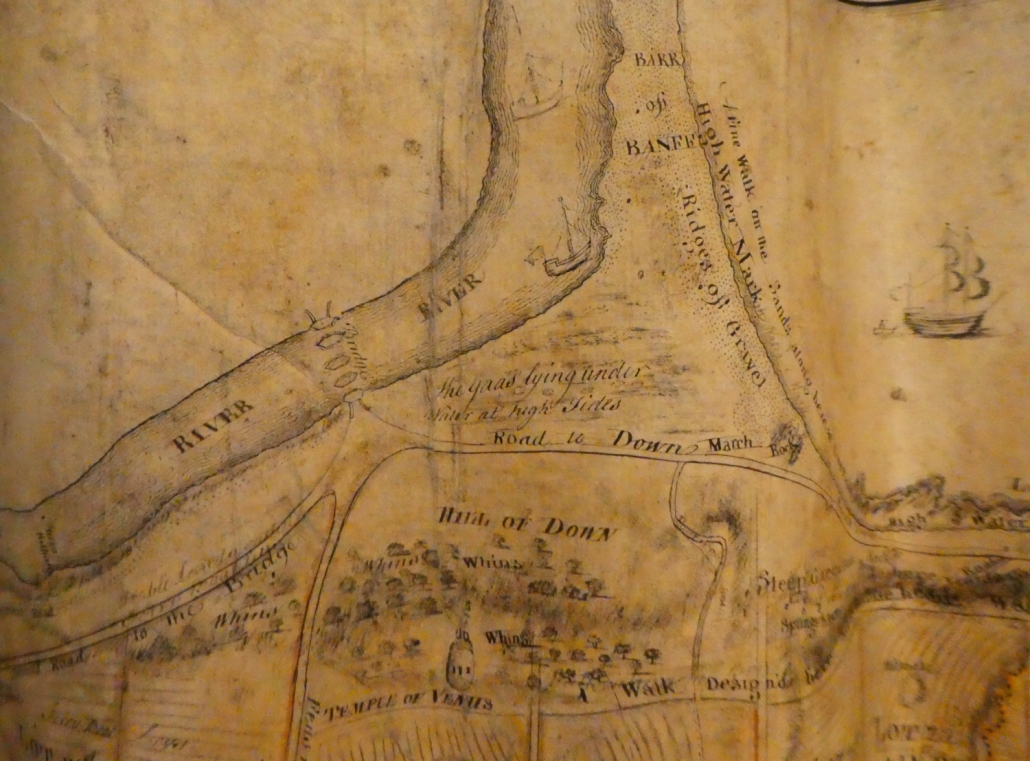

The earliest map that shows any level of detail for Banff or Macduff is dated AD 1600 and names the towns of Banff and Doun, also the settlements of Gellymill, Barnhill and Tarlair. But it also shows the shape of the river mouth, clearly indicating the bar coming from the Doun (Macduff) side. This expanded estuary covers a much larger area than the river does today, and may well have included not just Greenbanks, but the low lying land where Duff House now stands.

The next image is the first indication of what is a harbour, essentially shared between both Banff and Macduff. Unfortunately it is a century and a half later before there is another map that gives any detail of the area. This is the map produced by General Roy in the aftermath of Culloden, to inform the government of potential routes for it’s army around Scotland. The bar from the Macduff side is clearly still shown, with Greenbanks still submerged. Duff House is now shown (“Braco’s House”) and the Temple of Venus.

The very detailed map of Macduff in 1763 shows not only the shape of the river, but clearly how the river mouth is used by substantial ships (of their day) as a harbour. Interestingly this map also shows the piers of the first Banff Bridge, not reportedly completed until 1765. This map was commissioned as part of the town planning for the new town of Doune – not named as Macduff until 1783.

Note: the next available maps are 1772 and 1775. The former does not show any Banff Bridge, as it had been swept away in 1768. The Taylor & Skinner map of 1775 shows the new Banff Bridge.

There are also some images which clearly show the estuary, inland of the Bar, being used for shipping. The colour drawing is 1839. The black and white photos are late in the 1800’s. By then there was a shipyard on the Banff side of the river mouth.

Peter Anson came to this area in 1936, staying at 2 Braeheads Banff. Two years later he bought and moved into 2 Low Street Macduff, known locally as ‘Harbour Head’. Over the course of his lifetime (1889-1975) he published over thirty books, many dealing with the sea and its ships, and others focusing on his other love, the Catholic religion. Of all his books only one could be described as a best seller, How to Draw Ships (1940). He also produced many drawings related to the sea, some of which are on display in Banff’s Museum.

Peter Anson was born Frederick Charles Anson in Southsea on 22 August 1889, to prosperous parents. He converted to Roman Catholicism in 1913 and was received into the Third Order of the Franciscans in 1922, adopting the name Peter. While living in Macduff he turned the loft of Harbour Head into a small sacristy, where visiting monks would say mass for visiting mariners: Peter was no longer a member of the Order. The area of the sacristy was minute and containing as it did an altar table and other religious equipment had little space for church goers, not that there were ever many. Despite the lack of church goers, Peter took satisfaction from having it known that Macduff was the only port in Scotland with a Catholic chapel set apart for mariners.

During his time in Macduff (1937-1952) Peter was acquainted with notables, such as Neil M. Gunn and Compton Mackenzie, and became involved in the early activities of Scottish nationalism. Indeed, the Scottish Nationalist Party invited him to write a pamphlet which appeared with the title, The Scottish Fisheries: Are they Doomed? (1939).

Peter had a great personality and had empathy for fisher folk and they for him. There are not many public memorials in Macduff, but it comes as no surprise to find there is a sculpture in memory of Peter Anson.

Willian Geddie was born in Garmouth on 21st July 1829 into a Speyside shipbuilding family. He served his apprenticeship in Garmouth, later working as a shipwright in Glasgow and Aberdeen. His brother John was born in 1823 and had built three ships in Lossiemouth before going bankrupt in 1863. In 1865 both brothers migrated to Banff and built at least 27 ships mostly at the Duffus Hillock yard near the mouth of the Deveron but also at Patent Slip, Banff Harbour.

William Geddie 1829-1897

All the ships built by the Geddies were built of wood and carried sails. They were used for trading along the East Coast and for voyages to the Baltic countries. Most of them were owned by Banff or Macduff merchants and carried general cargo such as: coal, herring, grain. While they were judged to be fine ships by Lloyds of London, sailing was a dangerous undertaking as evidenced by the fact that of the 27 ships built by the brothers, at least 17 were lost at sea, in some cases with all the crew.

The launching of the Lady Ida Duff illustrates how difficult it could be to manage these boats. During the launch the ship’s bow lightly touched the seabed causing her to roll from side to side. The crew had almost managed to steady her before a slight breeze caused her to roll again. This movement was greatly amplified by the ship’s visitors, mostly boys, rushing to the shore side of the ship for some reason. The ship toppled over and a great number of those on board were tipped into the water. Fortunately, they were all rescued. During the next high tide, the ship was righted and moored.

The advent of steam-powered ships and the railway network spelt the end of sailing ships and their shipbuilders. The last ship built in Banff, the Swift, was on the stocks for three years waiting for a buyer. Eventually the Geddies had to become the managing owners. Tragically the Swift was lost at sea in 1896, less than a year after her completion. Six men were lost with her, including two of William’s sons. William died heartbroken in 1897 and with him went a great Banff industry that carried the name of Banff far and wide.

Walking past the harbour, partially repaired, raised questions about the railway pier and how the harbour had developed. The harbour in Banff is fascinating as for many years it was the home to fishing boats but also ships that sailed the world, bringing in raw materials needed in Banff and the surrounding area and exporting goods from this area.

The earliest mention of a harbour or safe haven is stated by Cramond (The Annals of Banff) to be in 1471, when the “Peel Heife” or Peel Haven, was next to the area used as the site for rebuilding the Kirk of Banff,St Mary’s Kirkyard, and that it had previously been where “boats and small craft were generally moored”.

In the early 1600s, plans were made for a harbour at Guthrie’s Haven and in 1625, James McKen, Fraserburgh, was employed to clear Guthrie’s Haven of rocks. (where the harbour is now) Records were found of people contributing £88 14s. 10d. towards building the harbour in 1626.

By the 1730s the harbour was still not complete and the town was unable to complete the work within a year as funds were low, despite gaining funding from across Scotland by voluntary contributions, so the storms in winter destroyed much of the work undertaken in the previous summer.

A renewed effort brought more contributions from across Britain and Europe e.g. Provost Hamilton in Bordeaux sent strong claret which was “rouped for eight guineas” and an order was issued by the Council for “a man from every family in town to work for a whole day or two tides, for carrying off the chingle thrown in to the harbour of Guthrie”

By 1760 there was “a basin with two piers, in which a ship of a hundred tons can lie with safety”.

By 1770 a new harbour was planned and the foundations were being laid, according to a plan by John Smeaton.

By 1818 further improvements were needed and a plan was drawn up by Mr Thomas Telford. The works were to cost £14,000 and consisted of building new piers. The work was not without problems as a storm in 1828 wrecked part of the partially built pier and the pier then had to be built higher and thicker.

Throughout its existence regular maintenance and improvements have been needed.

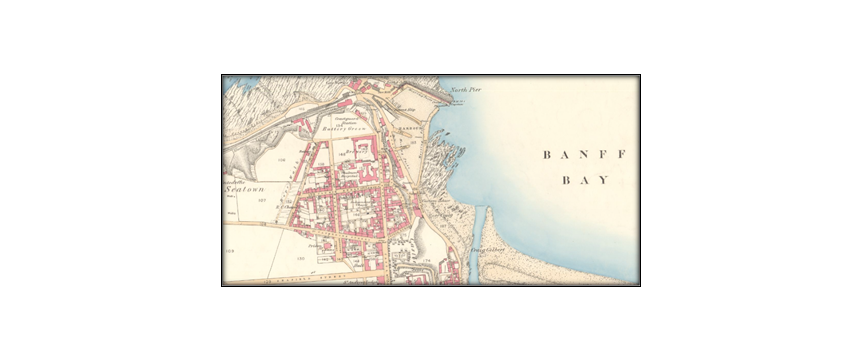

From approximately 1859 to 1910 the Banff, Portsoy and Strathisla railway ran right to the harbour but in 1910 the link to the harbour was dismantled. It can be seen on the map of 1866. The National Library of Scotland has several maps of Banff that show how the harbour has changed over time.

The harbour has faced periods of great prosperity and some really difficult periods so hopefully better times will return soon for this wonderful historic harbour.

At 83 foot long and 21 feet in beam, the schooner “Baron Skene” was launched by John and William Geddie in Banff on 18th April 1874. She was a single deck, two masted, wooden hull sailing ship, and presumably well liked by her owner, W Morrison. She was surveyed and Classed with Lloyds Register of Shipping. On the 3rd May 1874 she sailed in ballast from Banff harbour bound for St Petersburg. (This picture is a close sister vessel built a couple of years later but with the same dimensions by the same builder).

It is not known for sure, but it seems likely that she had been named after James, the 5th Earl Fife, raised in 1857 to the British peerage as Baron Skene. This enabled him to sit in the House of Lords; he was also Lord Lieutenant of Banffshire. His son, Alexander, the 6th Earl, later became the first Duke of Fife.

The schooner, Baron Skene, unfortunately didn’t have such a good life as her namesake, the 5th Earl.

While the next event in the schooner’s life is now a matter of record, one local document has recently been found to make reference to her. John Donaldson was an apprentice gardener to the Earl Fife, working mainly in what is now known as Airlie Gardens – but used to be the kitchen garden for Duff House – with it’s Vinery that had been erected just a few months earlier. John was keen to make a career from gardening and so throughout his first (and second) job, he kept a diary. Like all gardeners at the time he worked Monday to Saturday, and had Sundays off.

In 1874, today 3rd May, was a Sunday. He admits he only got up about 11 o’clock – he was only 18 years old! He goes on to say “Over at Macduff in the afternoon seeing the new ship that was smashed on the rocks this morning”.

So the schooner “Baron Skene”, with her Captain W Mason, had managed to sail about a mile, believed to have hit rocks to the southwest of Collie Rocks. She was assisted off the rocks and into Macduff harbour. No records of her since that fateful day of 3rd May 1874 seem to exist so perhaps the damage was really bad – perhaps as described by John Donaldson as “smashed”! Not a particularly auspicious start for a brand new vessel.

The reason for her hitting the rocks is not known; John Donaldson describes the weather every day in his diary – and that day was just recorded as “dull cold day”; if it had been windy he would have used the word “rough”.

In December 1891, a Miss M’Donald, gave a “recitation” of the “Loss of Baron Skene” in Portknockie at the Seafield Church Soiree (accordingly to the Aberdeen Journal); was this a poem, or a song, or a story?. If anyone has a copy it would be great to see it!

Refer to part 1 for George’s international influence.

George continued his trading after the “Lady Hughes” incident and seemingly was quite successful. He had a local family, although not formally married. In 1789 he determined to make a trip back to Scotland, but after rounding the Cape of Good Hope he was taken ill on board the “Winterton” and passed away on 22nd January 1790 aged 52. He was buried at sea.

But most fortunately he left a Will. His daughter Felicia in Bombay was well provided for, but a large part of his fortune he left to his five sisters – at least one of which, Jean, lived in Banff – at an earlier No 1 St Catherine Street.

Two of his sisters however never came forward, and George had obviously expected this because his Will allowed for that event. The unclaimed monies (circa £2 million in today’s money) were put in the care of the magistrates of Banff, and as his Will specifically directed it was called the “George Smith Bounty”. He had two specific provisions: firstly to build a school in Fordyce – his place of birth, a stated salary for the schoolmaster, and an endowment for children that could prove a connection to the Smith family. This seems to have taken place and very successfully.

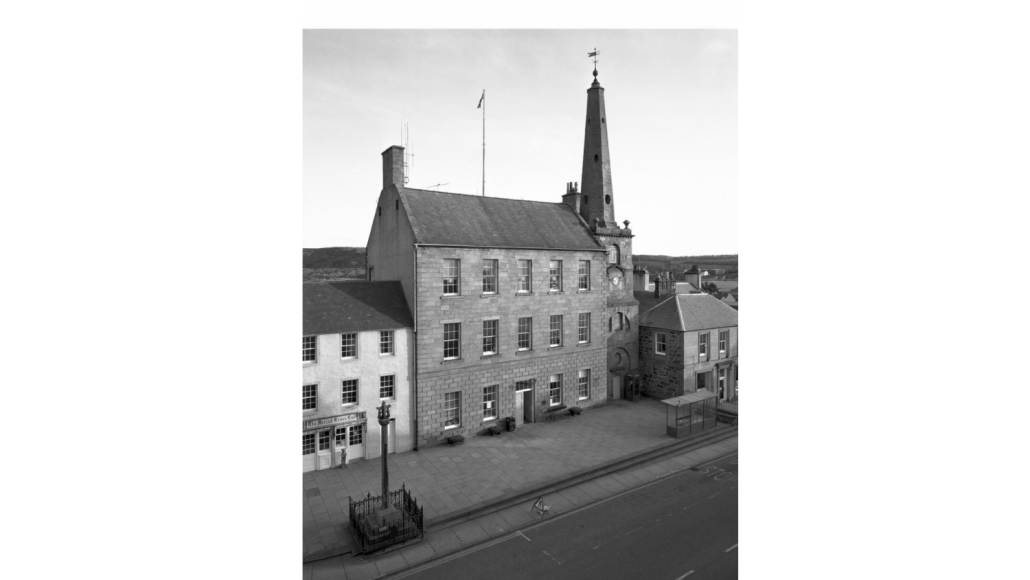

Secondly, for Banff, “an Hospital” should be built. The Town Council at the time, as is recorded in their Minutes, decided in 1815 however that the amount was insufficient for a hospital and instead they elected to extend the Townhouse – which had been built in 1796. Which part of the building this was seems unclear, but presumably part of the rear extension. The 1823 detailed map of Banff does not show the extension to the south near the now Carmelite House Hotel. And the “houses” to the north – although owned by “the Town” existed before the present Townhouse.

The local politicians of the time defended not building a hospital by making the extension Townhouse useful to military when quartered in Banff and “for several years it has been employed most beneficially as an hospital of sustenance and health for the lower orders, from whence they have received a supply of good wholesome broth and bread three times a week”.

Although the wonderful phrase “hospital of sustenance” cannot be found anywhere else, a Report by the Commissioners on Municipal Corporations of Scotland in 1835 did conclude the donor’s “intention has in substance been carried into operation”. They also said that while this practice “is not an example to be followed, it can hardly be censured”.

So thank you George Smith for helping Banff, Fordyce and Hong Kong.

Note, George Smith was quite a common name back then amongst Scotsmen; at least two other influential Scots George Smith’s in trade in the east, and another different one is buried in St Mary’s churchyard in Banff.

From 1702 until 1815, the French and British were involved in six wars. In the wars, merchant ships suffered heavy losses off of the North East coast. The merchant ships were attacked by privateers of mainly French origin, although privateers of American and Dutch origin were active too.

Privateers were privately owned ships, commissioned by governments to attack the merchant shipping of enemy countries and disrupt their trade. The fate of ships captured by privateers varied – their cargoes and the ships themselves could be sold, refitted or burnt. Often their crews were allowed to return home. The Moray Firth was a busy shipping route at this time as ships would sail around the top of Britain to avoid trouble in the English Channel.

The most noted incident was in 1757. On the 5th of October, Francois Thurot, in command of the frigate Marischal de Belleisle and several other ships, appeared in Banff Bay, much to the distress of the people of Banff. The plan seemed to be to invade Banff, plunder and destroy it with a force of 1100 men. The people of Banff were saved though, by a storm, a gale which forced the ships to cut their cables and flee.

In 1777 the Tartar of Boston, an American privateer, captured Lord Fife’s ship – the Anne of Banff – (amongst others). Lord Fife feared he would not be safe living at Duff House “We shall be burnt and plundered”

By 1781, in response to the threat, a very fine battery of 9 eighteen pounders were erected at Banff above the high ground above Banff harbour. This is where the name Battery Green comes from. As well as this soldiers were stationed along the Moray Firth coast.

Ultimately, the focus of transport shifted from the sea to overland routes and led to the building of the first bridge at Banff.