George was born in 1737 just along the coast from Banff in Fordyce. The family seems to have had Jacobite connections so after the failed uprising in 1745 spread out across the world. As George grew up he travelled from Holland overland via Syria to Bombay arriving in 1768. That must have been some trip! There he established himself as a private trader, both in India and China, trading a lot in tea which at that time came mostly from China. At times he acted as “Supercargo” on ships, ie the person representing the owner of the cargo – often himself. The network of Supercargoes in India and China were the people that controlled all trade in the area, although of course trading in China – Canton (now Guangzhou) being the only allowed port for foreigners – was subject to various Chinese rules. There was no British Embassy in China at the time.

In late 1784 George was the Supercargo on board a ship called the “Lady Hughes”, berthed alongside in Canton. It was the practice to honour other foreign ships leaving harbour by firing a gun salute – all cargo ships at that time were armed merchantmen. So the Lady Hughes gunner fired his customary salute as a Danish ship was leaving port – most unfortunately he hit a Chinese boat and killed two crewmen! George was arrested as the most senior person on board, but the other Supercargoes did not take kindly to one of their own being detained and all the foreign ships – armed – lined up to blockade the harbour. The Chinese responded with their own warships and there was a standoff. Fortunately it seems the local Chinese governor (Sun Shiyi) was reasonable and a compromise was negotiated, the alleged gunner in question being summarily strangled as was the Chinese custom.

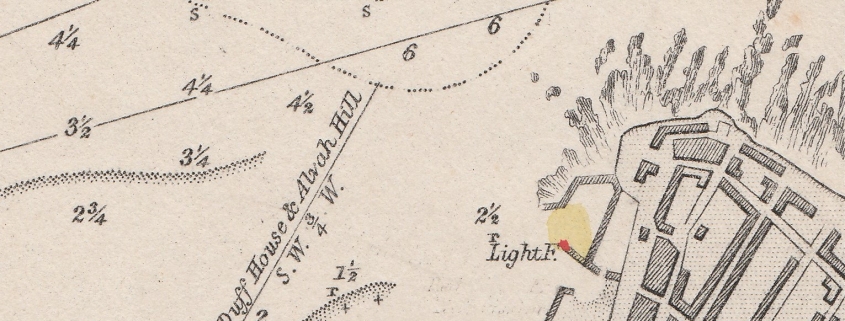

The painting is of Canton Harbour in the late eighteenth century, showing an armed merchantman as well as a multitude of local boats, in front of the international warehouses of the time; painted by Daniell (it is thought both father and son).

When word of this serious incident reached the UK, the existing government policy of wanting a trading outpost in China outwith the laws of China was re-inforced. An embassy and outpost was created, but it was decades later, after China’s financial crisis and inability to re-pay debts, plus Britain militarily defeating China in the first Opium War, that Hong Kong island was formally ceded to the British in 1842.

George may have only played a tiny un-intended part in the creation of Hong Kong, but part of his legacy still stands in the centre of Banff today – and the Story of how that came to be, will be told in Part 2.

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB