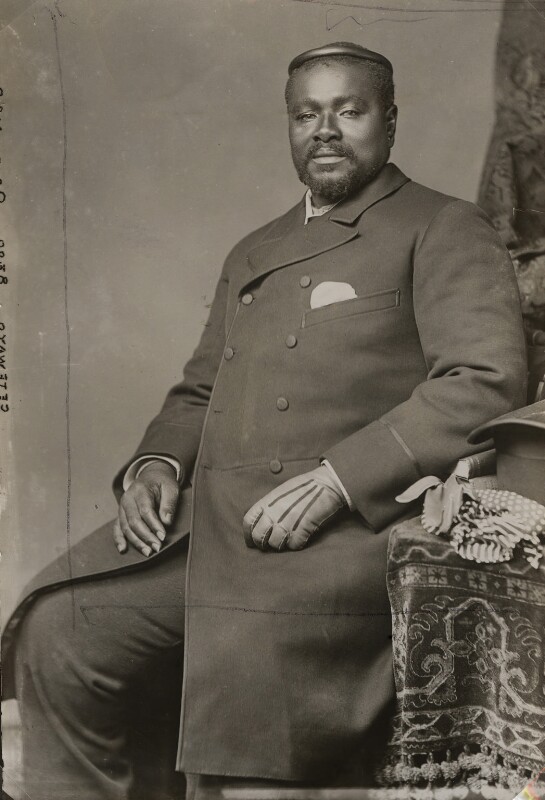

King Cetshwayo was the last Zulu King. At the time British people spelt the name Cetewayo, but nowadays it is more likely to be Cetshwayo, closer to the actual pronunciation. After a long and brave fight by the Zulu army, the King was captured after the battle of Ulundi in 1879 by Major Richard J.C. Marter of the Kings Dragoon Guards. Colonel Harford described the moment King Cetewayo gave himself up – “the King …strode in with the aid of his long stick, with a proud and dignified air and grace, looking a magnificent specimen of his race and every inch a warrior in his grand umutcha of leopard skin and tails, with lion’s teeth and claw charms round his neck”.

Was this the same stick which was taken from him? In 1882, Mr F.C. Lucy took a collection of these valuable items back to Britain after a trip to South Africa. The list was long and included Cetewayo’s stick, 13 throwing and stabbing assagais (light spears), 3 knobkerries (clubs), clothing with bead work, 2 Kaffir pipes and 2 Zulu pipes, as well as a number of natural history objects.

These were donated to the Banff Museum by Mr Lucy of London, via his mother-in-law Mrs Ewing, who lived in St Catherine Street. The walking stick is listed as being in the museum in 1919 (Banff and District by A. Edward Mahood). After this it is difficult to track what happened to Cetewayo’s stick until it turns up in the British Museum in 1963. It is there listed as being previously owned by Cetshwayo kaMpande, Banff Museum, and from the collection of Captain A.W.F. Fuller.

Captain Fuller was referred to as “an armchair anthropologist”. He was born in Sussex and trained as a solicitor but at the outbreak of the First World War he signed up with the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and became a captain. He built up a vast collection and he refused to sell anything until shortly before his death when 6,800 items from the Pacific were sold to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. The rest of his collection was dispersed by his widow. The clue as to how Cetewayo’s stick went from the Banff Museum to Captain Fuller comes from newspaper articles which state that in 1938, the then town council, brought in Mr Kerr of the Royal Scottish Museum to assess their collection and he recommended that a large number of items from the museum should be disposed of as they were not local to Banff. Could it be that Cetewayo’s stick was sold then?

© The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum