In 1759 General James Abercromby (aka Mrs Nanny Cromby) retired from the army and returned to his Banffshire estate, Glasshaugh. With plenty of time on his hands he commissioned the rebuilding of Glasshaugh House in a classical style, see above.

Fast forward to the 21st century. The house still exists but in a ruinous state. Not surprising since in the last century it was used to house livestock, ‘chickens on the second floor, pigs on the first – who reached their pens via the principal staircase – and cows on the ground’.

Back in the 18th century, James’ thoughts turned to land improvements on his estate. But what to do?

- What about a mill?

- A mill??

- A windmill would be fun!

So, a windmill it was. While windmills were not unknown in Scotland, most mills in the area were water driven. In construction, two essential components required are labour and materials. Fortunately, labour was readily available in the form of large numbers of tenant farmers and cottars locally displaced in a manner reminiscent of the Highland Clearances. Materials were available in the form of a nearby Bronze Age burial cairn.

To the utter astonishment of the local population around Banff a gigantic four-story windmill was completed and dressed in splendid white sails. It was the talk of Banff and beyond. It still is, but now known locally as the Cup and Saucer. Not surprisingly travellers who pass it on the A98 between Banff and Portsoy have no idea what it is. Could it be a Martello tower, Pictish broch, a tower house, a part of the nearby Glenglasshaugh Distillery??

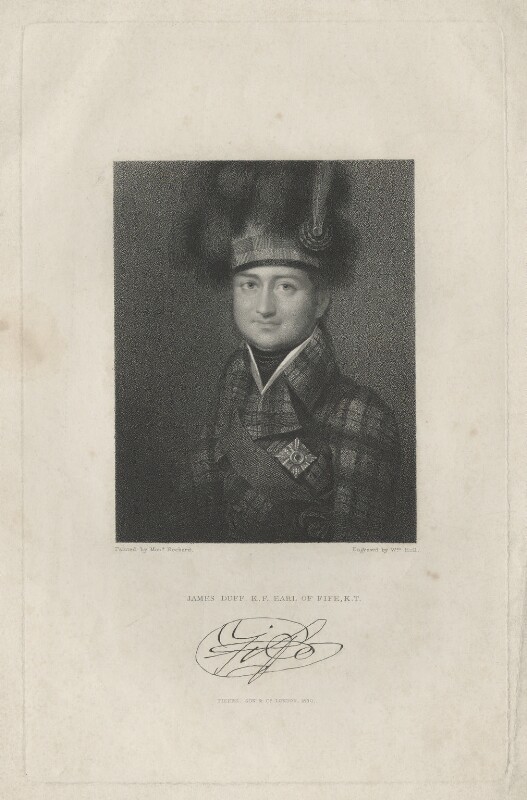

James Abercromby, defeated general, nanny, wind power visionary, destroyer of Bronze Age remains? We will let his wife, Mary Duff, have the last word. She ended the inscription on his gravestone at Fordyce:“… his once happy wife inscribes this marble as an unequal testimony of his worth, and of her affection.”

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB