Many thanks to Douglas Lockhart and the Scottish Local History journal for the background to this Story.

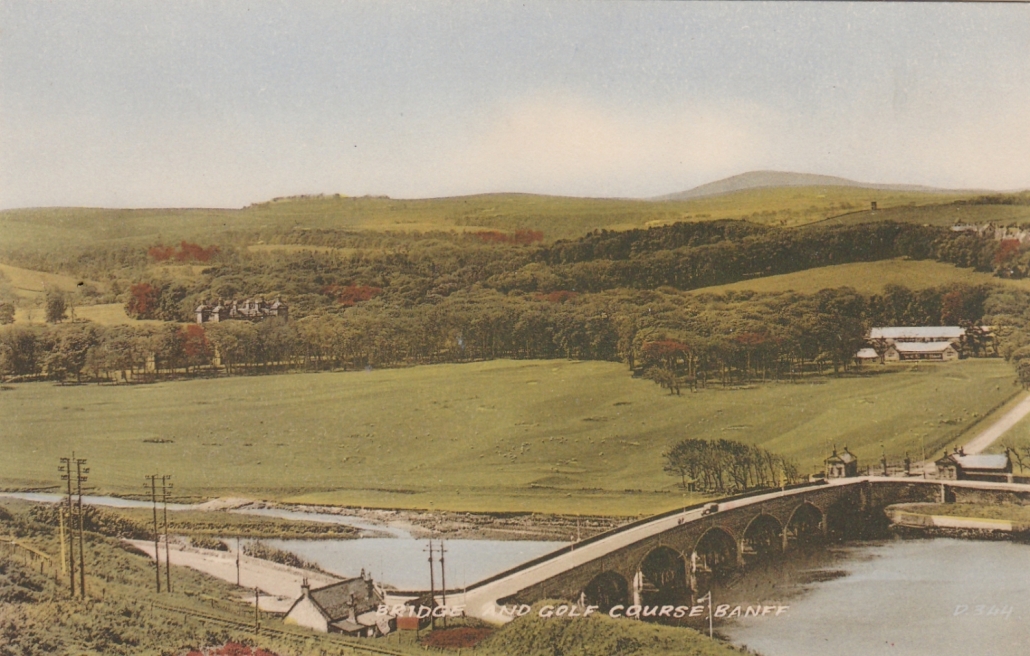

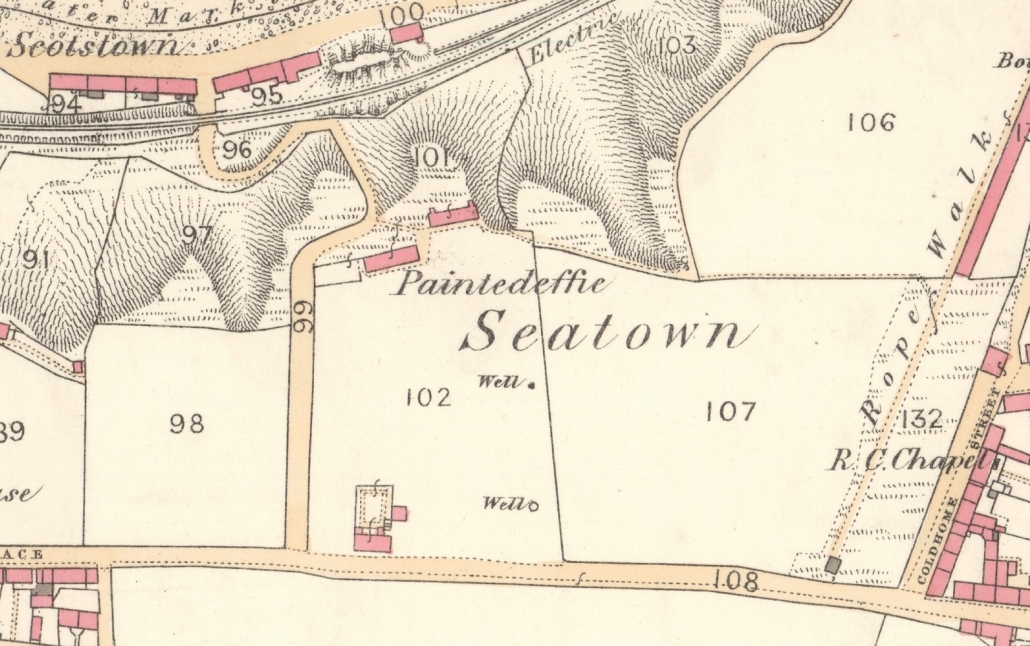

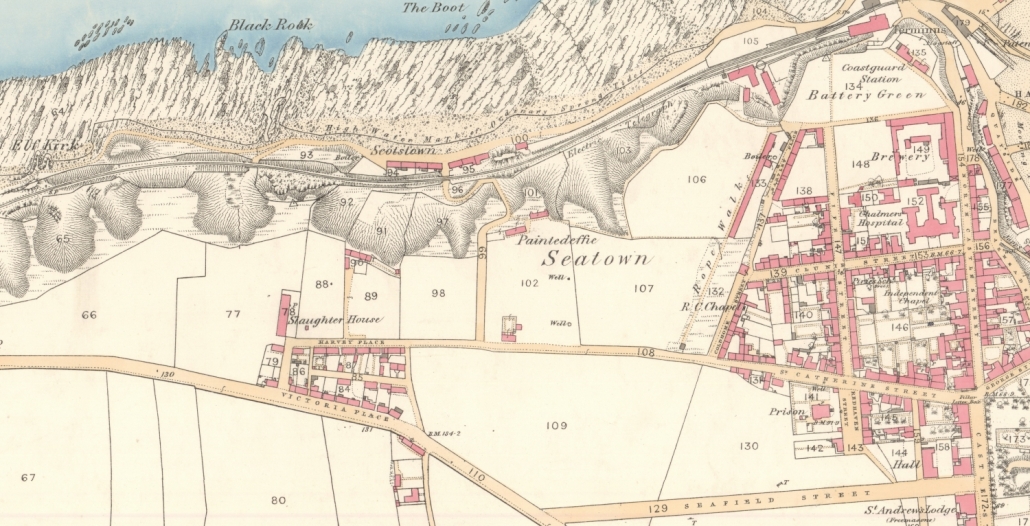

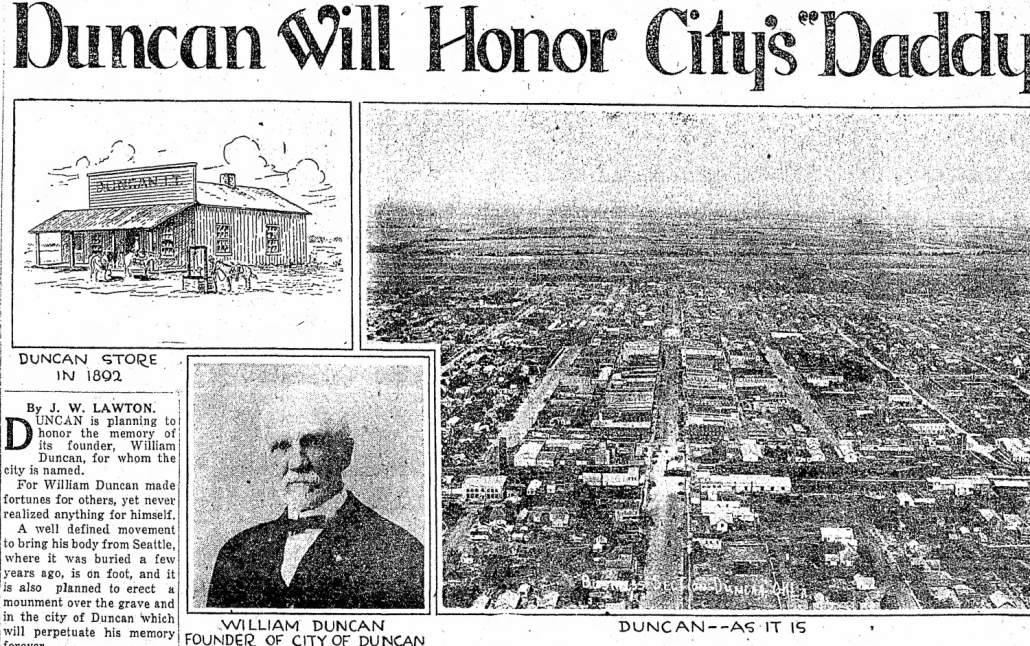

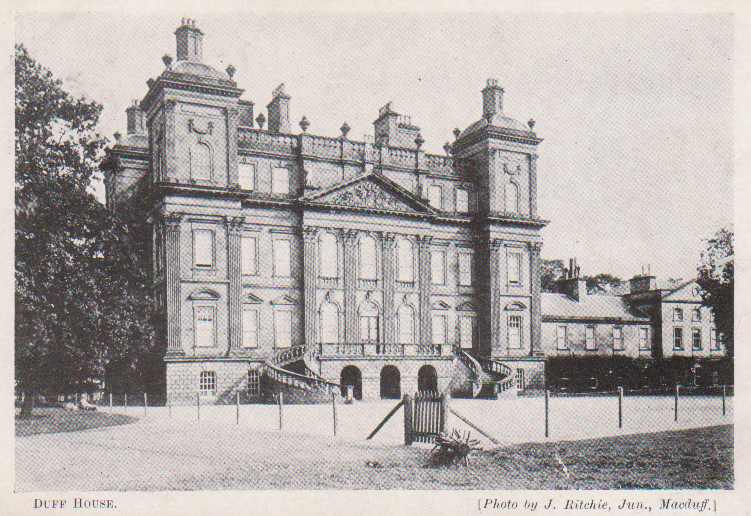

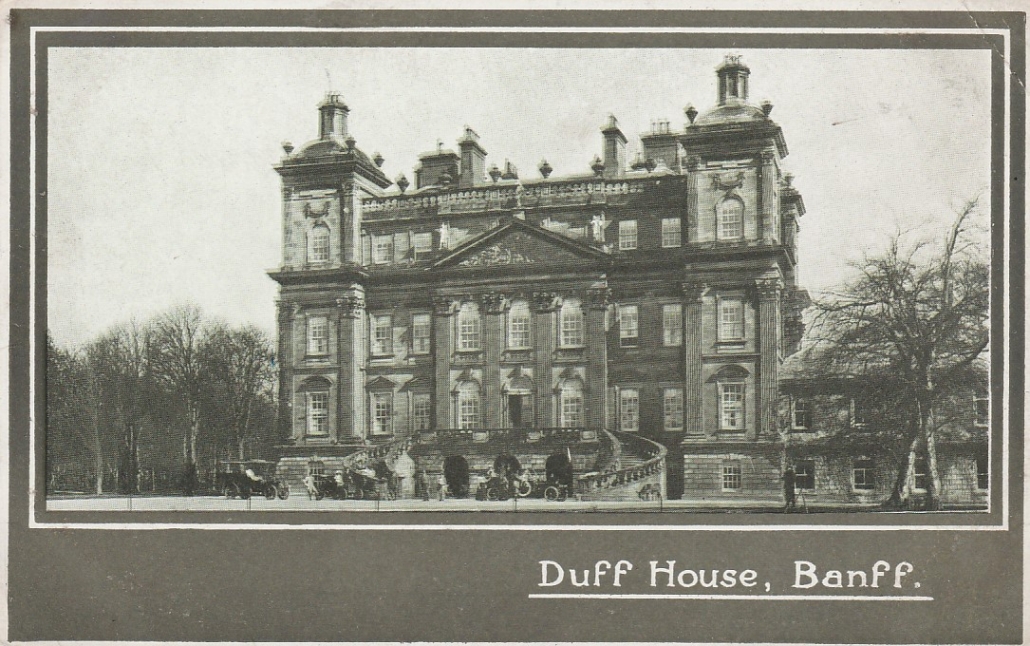

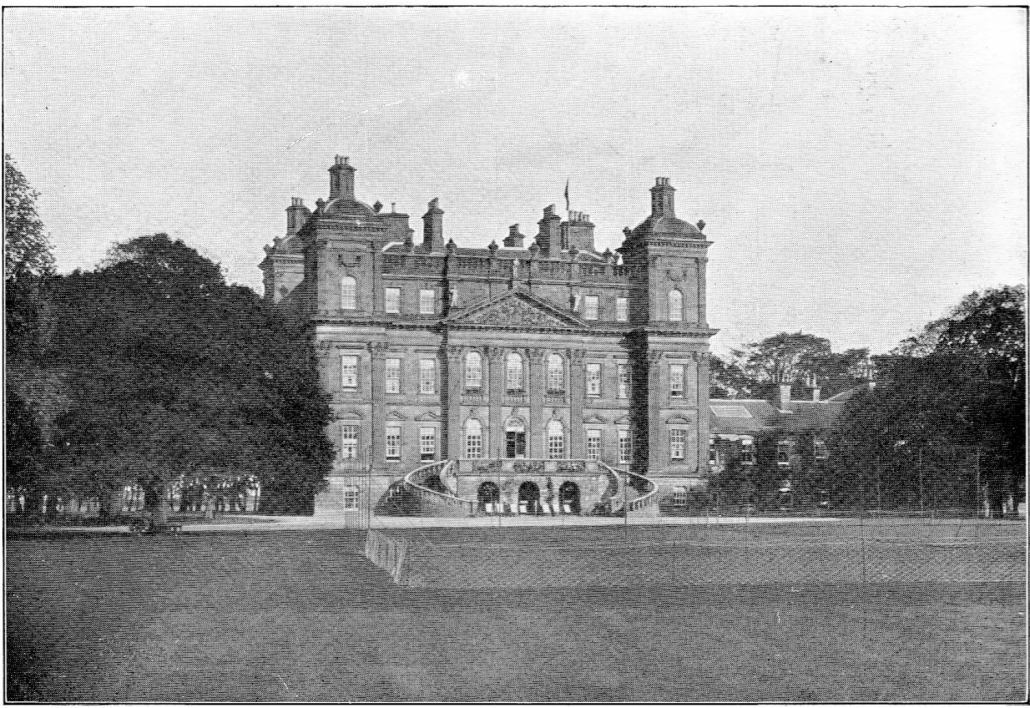

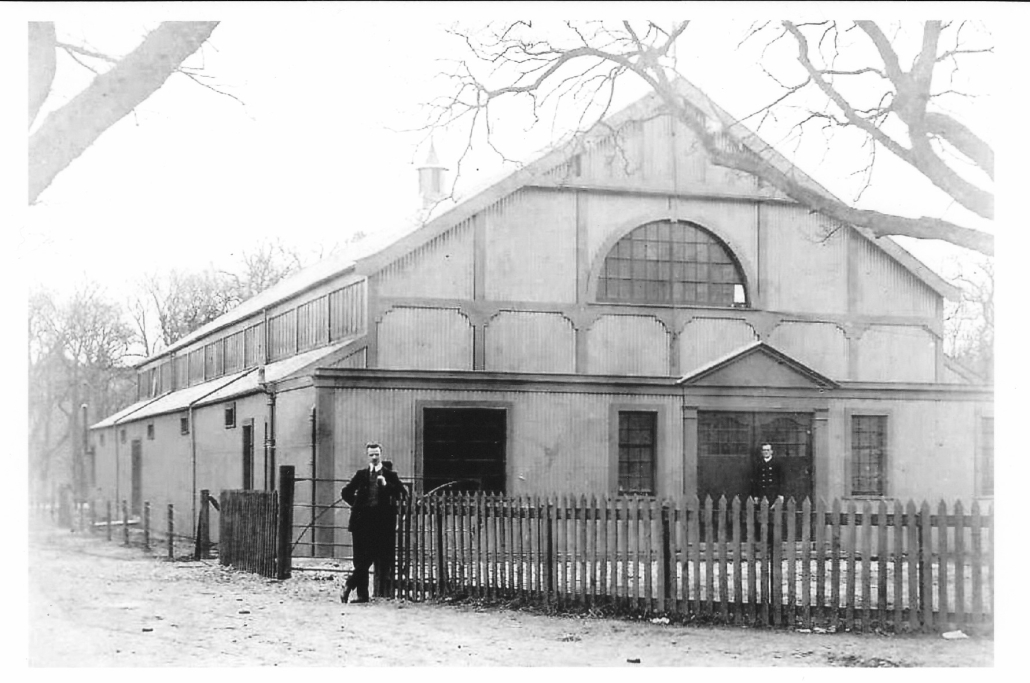

In 1908 the American Roller Rink Company established skating rinks in four Scottish Cities. This became so popular that dozens of rinks followed in many Scottish towns. Some rinks were in converted premises, and sometimes there were touring rinks. However the rink in Banff, opened on 8th January 1910, was a specially built one, sited at The Barnyards – behind the Duff House Golf Club – on the present car park. The Rink can be seen in the headline photo of Duff House grounds, to the right just above centre; the smaller building in front was the original Golf Club House. This was three years or so after Duff House and the estate had been gifted by the Duke of Fife to the Burgh Councils of Banff and Macduff, and they had established Duff House Ltd; DHL opened Duff House as a hotel in May 1910, but had already laid out and opened the golf course (initially 9 hole), the skating rink and a number of other businesses by that time.

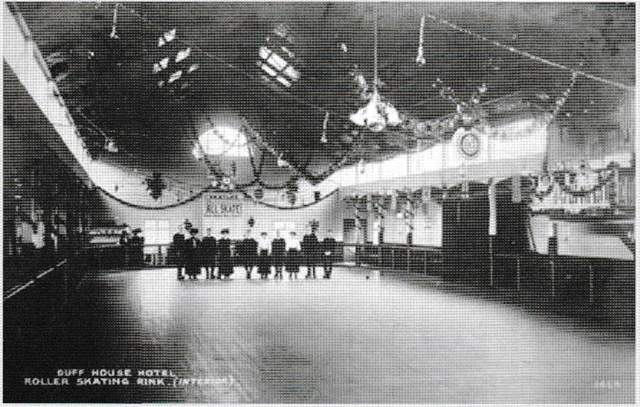

The Grand Opening of the venue was on Saturday 8th January 1910 at 3 in the afternoon! The floor space was 100 feet by 40 feet, with a wide promenade from the main entrance around the whole floor. The skating floor itself was laid with imported maple and highly polished. There was also a balcony on one side of the hall, plus cloakrooms, lavatories and a store for skate hire – the latest skates with ball bearings! The hall had been built by D McAndrews of Aberdeen, with the heating and lighting from companies in Dundee. The hall, “exceedingly crowded”R, was opened by Mr J E Sutherland, MP for the Elgin Burghs. The Macduff Brass Band and the Banff Pipe and Drum Band played outside, and at the far end of the hall there was a “fine orchestral organ”. It was claimed that the Rink was one of the finest in Scotland.

During the next four months or so the Rink was a hive of activity. Some of the events included a carnival and gymkhana held on 2nd February 1910: “So large was the turnout on the occasion that hundreds were unable to gain admission” reports the Aberdeen Daily Journal. On 2nd March there was a “Barnyard and Fancy Dress Carnival” held, with 50 people in fancy dress costumes, included a potato race, a speed race and musical chairs! An exhibition skate was given demonstrating the two-step waltz, the two step promenade and the “Dutch roll”. One of the highlights seemed to be Mr Brett, a local instructor, jumping over 8 chairs while wearing skates, believed to be a world record!

Skating was seasonal, and by April the season was drawing to a close. The fifth gala since opening was held, another event with fancy dress. The Banffie notes: “One of the most striking representations was that of the flying machine. Besides being entirely novel and original, the workmanship of the model was very realistically reproduced. The aeronaut, who was costumed in white, supported the framework of the car with his hands, while o his broad-brimmed cap rested the body of the “machine” whose cigar-shaped form was furnished with propellers.”

The Rink became a “Palace” during the summer, and it opened for the next season on 24th August 1910. A band frequently played, and on two afternoons a week, teas could be served on the lawn at the front of Duff House! A Miss Mab Holding, an accomplished roller skater, had been engaged, and she gave clever exhibitions of “trick and fancy skating, including threading a maze of lighted candles” to a large and appreciative audience. During the winter there were more Fancy Dress Carnivals, Polo matches and much more, but by early March 2011 the Banffie was reporting “the pastime of roller skating seems to be waning locally” apart from a few enthusiasts who quite often had the rink to themselves. The hall started to be used for a variety of other events, dances, concerts, bazaars, and by the end of 2011 skating was only two evenings a week.

By 1912 the hall was leased out as a Picture Hall and in July 1913 the Duff House Sanatorium, now the owners, had an auction of surplus goods including roller skates. It is not known exactly when the hall, or “Pavilion” as it was called in the Valuation Rolls was demolished, but it last appears in the Valuation Rolls for 1916/17.

Further thanks and acknowledgements for this Story go to:

The British Newspaper Archive and D C Thomson & Co for the newspaper excerpts;

Banff Preservation and Heritage Society for the internal photo.