Turnpike Trusts were established in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as a way of creating and maintaining a decent road network. The individual Trusts were established by Acts of Parliament. Turnpikes or Toll bars were points on the roads where people had to pay to use the road. The first Scottish Turnpike Act was in 1713 but it was the end of the century before turnpikes were built in Aberdeenshire and Banffshire.

There was a case for more roads. In the late 1700s, cargo ships from the Moray Firth were often attacked and captured by French privateers. For example in 1781 the “Anne” of Banff was taken by a Dunkirk privateer and Lord Fife lost many possessions. As the seas were so dangerous there was a great need for an alternative and safer travel route.

Also agriculture and industry saw considerable developments during this period so roads were needed to transport goods being produced.

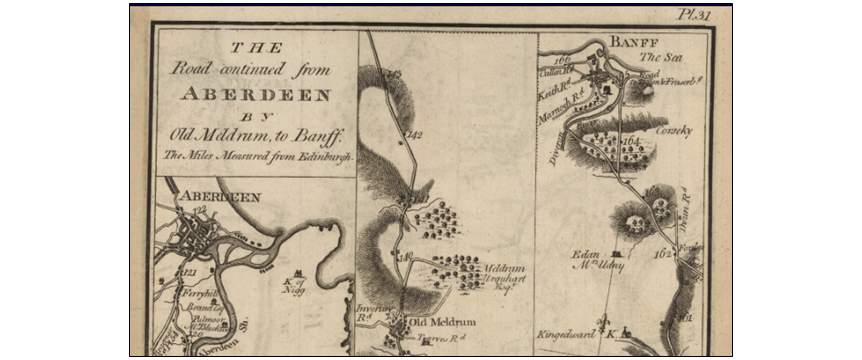

In 1796, the road from Aberdeen was surveyed and planned, allowing an estimate to be drawn up. In 1800 a general meeting was held in Banff because the road from Turriff to Banff was so bad that no one would carry the mail on the road without extra payments being made to them. The great Provost George Robinson obtained the necessary permissions to have the road built and in 1801, Thomas Shier was appointed as the road overseer as he had surveyed the route.

It all took time. In 1802 the first eleven miles of turnpike road between Banff and Turriff was complete. In 1804 the Head Court of Banff “authorize[d] the Magistrates to subscribe £500 to the construction of a turnpike road from the Harbour of Banff southward to Huntly by Inverkeithny and Marnoch.”

In 1804 “the Provost is authorized to subscribe a sum not exceeding £300 towards making a direct communication to Keith by a turnpike road from Cott-town of Ordens to the place where it will join the Portsoy turnpike, near the Kirk of Ordiquhill.”

Four turnpike roads led out from Banff – to Boyndie, Turriff, Buchan and Marnoch. Many of the toll houses can still be seen around the area, normally altered to suit the needs of today. The nearest example to Banff is the Toll house just South of the Gellymill. The first toll house was built in 1802 “where the Turriff turnpike intersects the Macduff road below Myrehouse”. It was made of turf and the keeper, John Morrison, was paid 1/- for each day. This was replaced by the permanent house “immediately below the Gellymill”.

By 1808 the system of toll roads inland from Banff was complete. Everyone was to pay the tolls except for soldiers and their carriages ‘on the King’s business’ who would be exempt.

By 1809 the demand by the military for a decent road through Banff to Fort George from Aberdeen reduced as other, shorter routes from Fort George south had opened up and the route along the Moray Firth coast was no longer so well used.

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB