The Banffshire Journal was founded in 1845 but it’s first Editor, James Thomson, lasted only little more than a year. For the next six decades Alexander Ramsay was the Editor, initially appointed when he was just 25. He had served an apprenticeship in Edinburgh – since the age of 13 – then worked in London, before coming to Banff in early 1847.

50 years into his job he told friends at his Jubilee, “Since the day I first entered the Town, I have never ceased to take a lively interest in its affairs. On nearing the east end of the Bridge, and looking out of the window of the coach, I saw the fair prospect of the Town resting on the slope of the hill, the river in the foreground, the sea to the right, the valley of the Deveron stretching southwards. I felt that I could live in this place. I have been so engrossed I work ever since that I had no time to think of a change.”

He started the regime of printing on Mondays for distribution on Tuesdays, and also appointed a correspondent in every parish, who weekly reported their local news to him. He made sure the paper covered not just local subjects, but everything he could think of interest to his readers. His political editorials tried to be balanced, which must have resulted in some discussion since his controlling shareholders were two Tories, the Earl of Fife and the Earl of Seafield!

He had many interests outside of the Journal itself. He purchased the copyright of the Polled Cattle Herd Book (“polled cattle” are those cattle breeds that naturally have no horns, such as Angus and Galloway) and published many editions, remaining it’s editor until 1901. At times he was also a Town Councillor, was Provost for two years, Chairman of the Parish Church Musical Association, and an Elder of the Church. Other posts he held were on the Banff School Board and Chair of the Banffshire Field Club.

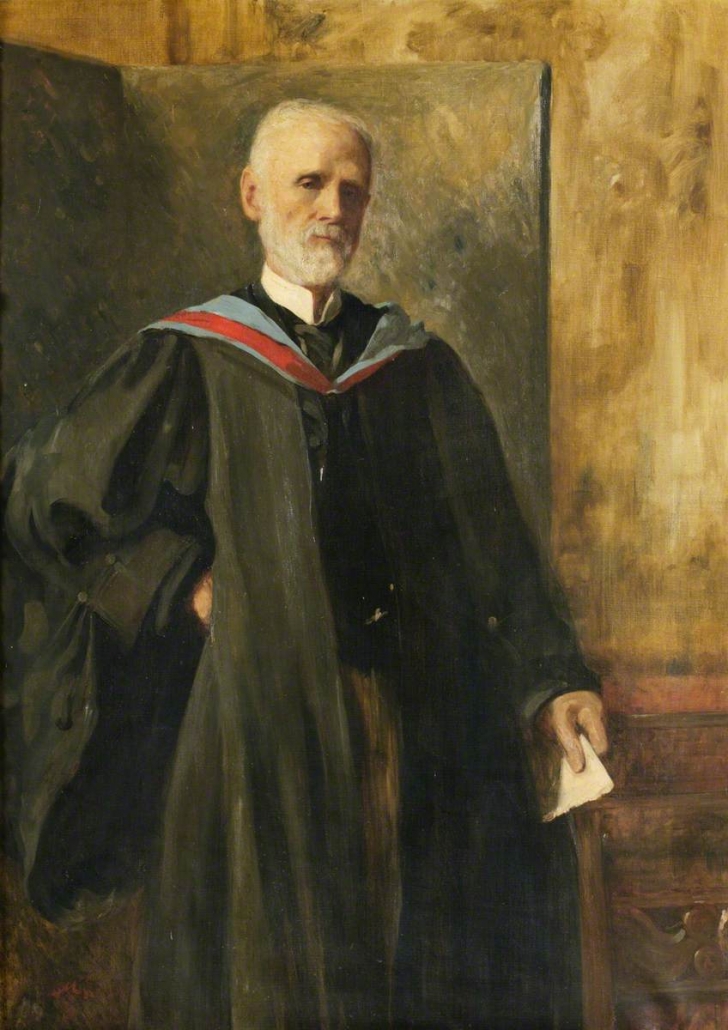

There was a large gathering for his Jubilee in 1897; at least 150 polled cattle farmers and many friends gathered in the Banff Council Chambers. One of the things he was presented with was his portrait, painted by Marjorie Evans, herself a grand-daughter of a Provost of Banff.

Dr Ramsay passed away in 1909.

BPHSMOB

BPHSMOB